The Assassination of President Lincoln

This week in 1865 - April 14th - President Abraham Lincoln was murdered in his hour of triumph

This week in 1865 - April 14th, which was in that year Good Friday - President Abraham Lincoln was murdered in his hour of triumph by John Wilkes Booth. Other conspirators attempted to kill Vice-President Johnson and Secretary of State Seward, in a last-ditch attempt to bolster the Confederate cause as the Civil War was drawing to a close. This attempt succeeded in a way, though not as any of them had hoped.

In April 1865, the American Civil War was ending. The Confederacy was falling apart before the Union armies and myriads of slaves walking away free. The Confederate government fled their capital (Richmond) on April 2nd; a week later on April 9th, Confederate General Lee surrendered after his starving army failed to maneuver fast enough to outrun General Grant's Union army. Meanwhile, General Sherman was marching through North Carolina, and captured the state capital of Raleigh on April 13th.

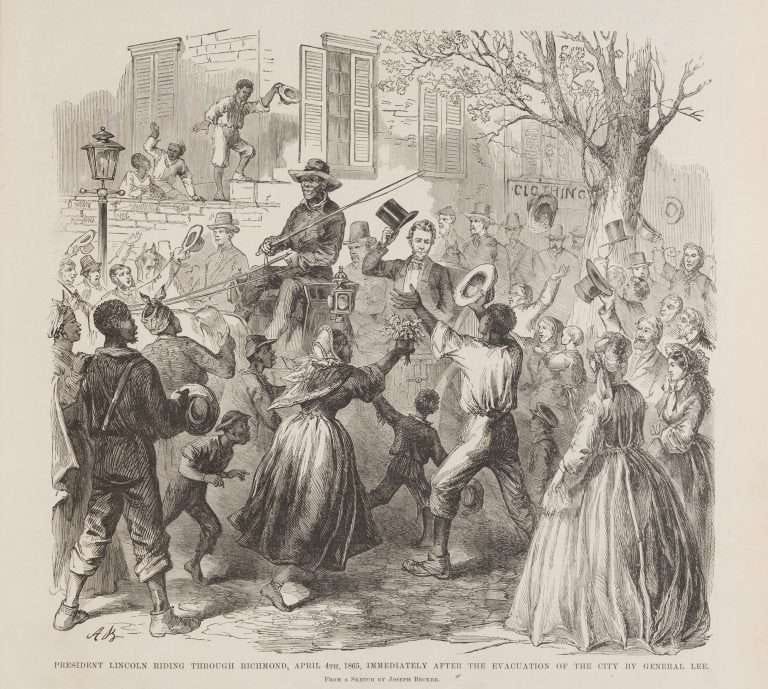

At the time, almost everyone saw the war was over. Confederate soldiers were deserting day by day - Lee's army that surrendered on the 9th was much smaller than the one that'd left Richmond on the 2nd. As President Lincoln toured Richmond on the 4th, he said "Now I feel like the President of the whole United States." On the night of the 12th, General Johnson - who commanded the sole Confederate army left in the east - told President Davis,

Our people are tired of the war, feel themselves whipped, and will not fight. Our country is overrun, its military resources greatly diminished, while the enemy's military power and resources were never greater and may be increased to any extent desired. ... My small force is melting away like snow before the sun.

Americans were eagerly awaiting the end of the war - Northerners who were hoping for their brothers or sons or husbands or neighbors to return from the war, soldiers looking forward to rest and peace, and the numerous slaves and former slaves who were welcoming their liberty. And, many of them were looking forward to Lincoln ("Father Abraham," as a popular song called him) to guide the peace.

Amid all this hope would come the shock that Lincoln was suddenly dead, murdered.

There were, of course, exceptions to this certainty of coming peace. One of them was Confederate President Davis, who proclaimed (from Danville, VA, while fleeing) "Let us... meet the foe with fresh defiance and with unconquered and unconquerable hearts."

Another exception was John Wilkes Booth, a famous stage actor and Confederate sympathizer in Washington, DC.

Unlike many Confederate sympathizers, as the war went worse for the South, Booth only grew more desperate to help their cause. In 1864, he started planning to kidnap President Lincoln. If he and his pro-Confederate friends could abduct him and bring him behind the Confederate lines, Booth was convinced, they could ransom him for any number of things - maybe even an end to the war.

However, the kidnapping plot was never actually tried. An ideal opportunity never came, and Booth and his friends' nerves weren't high enough to seize any less-than-ideal opportunities. I suspect they however-subconsciously realized that even if they had somehow kidnapped the President, conveying an unwilling prisoner down south through battle lines would have been very difficult. Finally (as the war continued), even Booth had to realize the collapsing Confederate lines were now impossible to reach.

After hearing a speech where Lincoln said that some black men deserved the vote - Booth vowed to instead kill the President. His friends planned to simultaneously kill the Vice-President and Secretaries of War and State. That speech - on April 11th, 1865 - would be Lincoln's last public address.

This was before Presidents had regular security; the one city policeman assigned to guard Lincoln had slipped away to get drunk. It was easy for Booth (a well-known actor) to slip into the theater aisles and the Presidential box while Lincoln was watching the play. He shot him unseen; Lincoln instantly fell unconscious.

Then, Booth jumped down onto the stage, calling, "Sic semper tyrannis!" - "Thus always to tyrants" - the words reportedly spoken by Brutus on assassinating Julius Caesar, and also the Virginia state motto.1

With that - having, in his mind, assassinated a tyrant - Booth ran out of the theater and out of Washington DC. After a furious hunt, he would soon die while trying to avoid capture.

(One of his friends would attack but fail to kill Secretary Seward, and another would lose his nerve before even attacking Vice-President Johnson.)

The nation mourned. Newspaper editorials pointed out that righteous Lincoln had been martyred on a Good Friday. Poet Walt Whitman (who had been volunteering in Union army hospitals) famously captured the mood in his "O Captain, My Captain".

The national mood simultaneously turned vengeful. Booth's friends and accomplices were all tried, and four of them executed. Even people relatively uninvolved were caught up: Booth's landlord Mary Surratt was executed (the first woman ever executed by the United States government), despite very flimsy evidence of anything beyond Confederate sympathies; Doctor Samuel Mudd was imprisoned for life for treating Booth while he was fleeing and not reporting him till the next day.2 Confederate President Davis himself was charged with the assassination, but no evidence could be found linking him to Booth.

This assassination changed history dramatically.

We don't know how Lincoln would have proceeded with Reconstruction. He'd made various statements, and advocated for even a few loyal men to organize governments in various states, but his policies had evolved during the war. As he admitted in his last public address, regarding his current support for a new Louisiana government, "I shall treat this as a bad promise, and break it, whenever I shall be convinced that keeping it is adverse to the public interest." His statement that some black men deserved the vote would have been opposed by most of the early attempts at reconstructing loyal governments.

What's clear, though, is that Lincoln would have been better than Johnson.

When the South had first seceded, Andrew Johnson became famous as the one Southern senator who refused to resign and stayed in Congress insisting that secession was invalid. He'd later gone to be the military governor of Tennessee, where (having risen from poverty himself) he hotly fought the planters and Confederate sympathizers. Despite being a Democrat, the Republicans nominated him as Vice-President in the 1864 election. The war was going poorly at the time; they thought they needed all the allies they could get. (In the end, Sherman's capture of Atlanta would've probably won the Republicans the election anyway - but that came well after the convention.)

After Lincoln's death, most Republicans expected Johnson to do what he'd done in Tennessee: to harshly punish secessionists and exclude from government everyone who had been disloyal. Some even gave thanks that the government was now in the hands of someone who'd manage Reconstruction more harshly than Lincoln.

But to their surprise, Johnson did the opposite. He handed out pardons all around and encouraged Southern planters to form new governments almost exactly the same as the old. Slavery was abolished, but almost everything else remained the same. In some cases, the old Slave Codes were reenacted with the word "slave" simply replaced by "black." But then, Johnson had never cared about black people; he'd even owned slaves himself. It was secession and the planters that he'd hated. And, for whatever reason, he was now happy to work with the planters - perhaps because he was now in power over them.

When Congress reconvened in December 1865, Senator-elects and Representative-elects who'd served in the Confederacy were there presenting their credentials from Johnson's new governments. Even Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens was there as a Senator-elect from Georgia.

Congress blocked them all, seized control of Reconstruction itself, wrote the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and sent the Army into the South to enforce freedmen's rights. But the damage had already been done. Encouraged by President Johnson, Southern elites would outlast Reconstruction until the North eventually grew tired of fighting.

So, in a way, Booth's bloodiness did win.

He didn't save the Confederacy itself, or slavery, but both of them were long beyond saving by that time. He did save a lot of the social system. By putting Johnson into the Presidency, he put what he would call federal tyranny in the South on a strict timetable - leading to renewed repression, continued discrimination, and exacerbated racial tensions to the present day.

(Of course, the freedmen didn't call that tyranny at all; they called it holding back state and local terror and tyranny.)

That said, Booth didn't mean to turn history this way - he'd sent his friend George Atzerodt to kill Vice-President Johnson! If Atzerodt had kept his nerve and succeeded, President Pro Tem of the Senate Lafayette S. Foster would have become Acting President until a special election later that year. I don't know who would have won that special election, but Foster was a vocal abolitionist who'd publicly stated that the war had done good in giving "the blessings of freedom" to slaves and eradicating "the canker of avarice." At the very least, any errors he made would have been in the opposite direction from Johnson's.

The story of history took an abrupt, and in many ways unlikely, turn that April 14th. Victory was half-turned to sorrow, and to grim resolve that would be largely frustrated.

I can only mourn for Lincoln, and wonder what would have been. His story had reached a fitting conclusion - but I wonder what he would have done in the next chapter of America's history.

The quote is often attributed to Brutus, whom Booth referenced, but there's no ancient source crediting Brutus with this phrase or any like it. It's disputed where it actually came from. Classics professor Mike Fontaine proposes it originally came from Scipio Aemilianus, upon the assassination of the Roman Republican populist politician Tiberius Gracchus, who was feared to be trying to become a tyrant. Regardless, it was popular in the Revolutionary and antebellum United States.

Two years later, yellow fever broke out in Dr. Mudd's prison and killed the prison physician; Mudd volunteered to take the job, served admirably, and saved many of his fellow prisoners' lives. After this, in early 1869, President Johnson pardoned him. He lived a quiet life afterwards, aside from some attempts to go into politics, but his name lives on in the saying "Your name is Mudd."