At the end of the American Civil War, the Union was saved, and the slaves were freed. But the nation faced a question: what would come next? "A new birth of freedom," President Lincoln had called it - but even those who agreed with him there disagreed what that new birth would look like.

The South was devastated: devastated from the war itself, from the blockade during the war, and from many freedmen no longer being interested in working at their old plantations. The old structure of society (built around slavery and racial hierarchy) had been torn down, and it was unclear what would replace it.

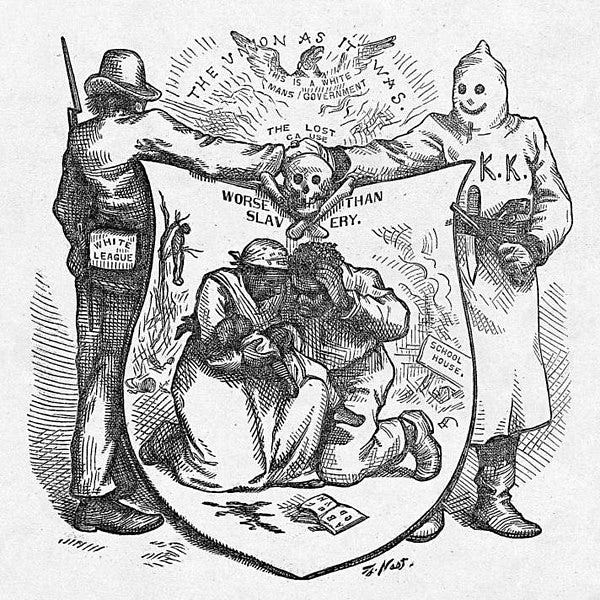

Like emancipation itself, and like most transitions in history, there're many stories of this Reconstruction era on the ground level. Also like emancipation, that ultimately determined much of the end of this period of Reconstruction. A sad end it was; an "unfinished revolution" as historian Eric Foner titled his book on the subject: thanks to massive racial violence from white Southerners, and a lack of Northern will to continue fighting, it yielded the era of "Jim Crow" discrimination.

But there were some triumphs - incomplete and largely delayed triumphs, but triumphs - brought by the statesmen in the federal government who tried to plan where this transition would go: largely through the three "Reconstruction Amendments" to the Constitution.

The first Reconstruction amendment was written during the war itself: the great and glorious Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. This solidified the huge change at ground level, but it was a huge change itself in legal theory. Previously, the Constitution had regulated the federal government and state governments. It allowed Congress to prohibit crimes against the government (such as treason and counterfeiting), but it didn't regulate daily life at all. Now, for the first time, the Thirteenth Amendment was changing that.

But then President Lincoln was assassinated by a Southern sympathizer, and Vice-President Andrew Johnson succeeded him. Johnson didn't care about slavery. He wasn't even a Republican. He was a Democrat, a prewar Senator from Tennessee, the one Southern senator who had refused to recognize secession and stayed in Washington DC insisting that Tennessee was still in the Union. The Republicans had welcomed him as allies (and other Democrats like him, such as the new Congressmen from "Virginia" elected by local Unionists), and they’d named him their Vice-Presidential nominee in the 1864 election when they were fishing for as much support as they could get.

Now that he was President, the radical Republicans1 at first thought he would at least be happy to punish the Southern upper class and secessionists - and at first he was. He pushed the Southern states to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery.

But that soon faded. Johnson wanted to restore the Southern states to the Union as quickly as possible. After all, he said, if they were full states in the Union (as the Union had officially asserted throughout the war), then how could anyone object to how they chose to organize themselves? New state governments were formed that were "new" in name only, with "Black Codes" often written by simply scratching out the word "slave" and replacing with "Black". When Congress assembled in December 1865 for the first time since Lincoln's assassination, they found dozens of former Confederates presenting writs of election from those state governments.

Congress declined to seat them. Instead, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, guaranteeing rights to "all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States" without interference from any state. President Johnson vetoed it; Congress overrode his veto.

This was the first time the federal government had tried to enforce individual rights against state governments. The Bill of Rights had applied only against the federal government. When (for example) the First Amendment said "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion...", it left states perfectly free to do that. For a while, many did - Massachusetts' established Congregational Church lasted until 1833. Congress didn't have any power to interfere with them.

Now, the Radical Republicans justified the Civil Rights Act as a way to enforce and complete the abolition of slavery by eliminating all its "badges and incidents."

But many - even many Radical Republicans, like Congressman John Bingham - objected this was unconstitutional. (Most modern scholars would agree this's stretching the Thirteenth Amendment too far.)

So, they wrote another Constitutional amendment, the Fourteenth Amendment. An omnibus amendment, it would explicitly allow the Civil Rights Act, but it would also do several other things to impede ex-Confederates from regaining power. To go through in reverse order:

Section 4 forbids the United States from nullifying its debt (including the large debt incurred in the Civil War), and also forbids the United States or any state from paying the Confederate war debt or any compensation to former slaveowners. In other words, if the rest of the amendment failed, the ex-Confederates would still be out of money.

Section 3 forbids insurrectionists from holding public office if they'd held public office before the insurrection, unless Congress lifted the ban. Most of the South's upper class would fall under this ban.

Section 2 says that if a state forbids any men from voting2, its representation in Congress would be reduced proportionately.

* Section 1 was the meatiest part:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

- in other words, the freedmen were in fact citizens.

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States

- in other words, the rights in the Bill of Rights applied against the states too; they couldn't deny them to the freedmen.

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

- and every law needed to be enforced equally for everyone, even the freedmen.

Shortly thereafter, Congress would require every ex-Confederate state to ratify this amendment before its Congressmen would be seated.

None of this mentioned voting rights, quite intentionally. There was a sharp distinction in political thought at the time between "civil rights" like the Fourteenth Amendment protected, and "political rights" like voting which it didn’t protect. Political rights would be protected three years later, with the Fifteenth Amendment.

(Before then, the Republicans in Congress would impeach President Johnson. Ostensibly, it was for dismissing Secretary of War Stanton, who favored Republican positions on Reconstruction. Really, it was for impeding their Reconstruction policy. But, the impeachment would fail.)

For all their noble aims, for a long time, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments mostly failed.

White people in the South continued to massively resist Reconstruction, Northern public opinion tired of it, and the federal government quickly followed. The Amnesty Act of 1872 waived Section Three's bar for virtually everyone, virtually mooting it until the modern era.3 The next year, in the Slaughterhouse Cases, the Supreme Court ruled that Section One's protection of "the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States" was so limited as to be a practical nullity. In 1876, US v. Cruikshank overturned the Civil Rights Act of 1870 and forbade the federal government from prosecuting the Colfax Massacre. By 1877, President Hayes withdrew the last federal troops from the South, leaving the freedmen vulnerable to mobs and discrimination.

Section Two - and the Fifteenth Amendment - remained on the books throughout the resulting era of "Jim Crow" discrimination and disenfranchisement, but without even any attempt to enforce them. The sole relic of the noble Reconstruction Amendments that remained in effect was the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery: a great and glorious change, but merely one part of what could have been. History had gone in a different direction from what the Radical Republicans had tried to design.

But still, the Amendments remained on the books. The Southern states could work around the Constitution to keep black people from voting, but they needed to work around it - unlike before the war, the Constitution said they couldn't discriminate by race. Similarly, they needed to at least call things "separate but equal," because "separate and unequal" was now against the law.

Yet, that meant little to most people on the ground level.

What did mean more to them was that, when public sentiment changed somewhat, the Amendments were there. Starting in 1897, and then more frequently through the 1900's, the Supreme Court invented the concept of "substantive due process" where (even without technically overturning Slaughterhouse) the Fourteenth Amendment did protect some of the Bill of Rights against the states after all.4 And then, when "Jim Crow" discrimination was dismantled in the 1950's and 1960's, it was done using these Amendments. Now, the Fourteenth Amendment is used every year to enforce civil rights against state governments as well as federal.

The transition went far differently from how it was planned, and sadly much delayed. In the end, it went far beyond anything most people of the time had thought. The Supreme Court's flabbergasted prophecy in the Slaughterhouse Cases has been fulfilled:

Such a construction... would constitute this court a perpetual censor upon all legislation of the States, on the civil rights of their own citizens, with authority to nullify such as it did not approve as consistent with those rights, as they existed at the time of the adoption of this amendment.

In other words, people would perpetually sue in federal court to overturn state laws in favor of civil rights. It seems pedestrian now - but that’s because we live after this great transition, and we’re used to it. People at the time could hardly believe it.

Yet, that was what Congress had indeed written. And it was warranted - nothing else but that "perpetual censor" would disrupt the "Jim Crow" establishment of the South. And the efforts of the Radical Republicans in the Reconstruction Congress did in the end prove fruitful.

The “Radical Republicans” were an informal grouping within the Republican party, of those Republicans who wanted to significantly promote black rights - in other words, to radically change Southern culture.

Specifically, "any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens... except for participation in rebellion, or other crime." At the time, some states did allow noncitizens to vote; no state allowed women to vote.

This is why there are so many open questions about Section Three in the modern era, when another ostensible insurrection makes it once again relevant: it was only in effect for a few years in most cases, and only litigated once (in a federal district court, in Griffin’s Case).

In the modern era, Justice Clarence Thomas has repeatedly called on the Supreme Court to overrule Slaughterhouse and rule that the Privileges and Immunities clause is what protects the Bill of Rights against the states. Unfortunately, no other justices have agreed with him. However, this would have no practical significance: civil rights are protected against the states either way.