Emancipation on the Ground Level

Juneteenth

This Monday, June 19th, is Juneteenth.

It's a new holiday in most of the United States, commemorating the abolition of slavery. This isn't when it was officially outlawed (the Thirteenth Amendment, on 6 December 1865), or even when the Emancipation Proclamation was proclaimed (announced 22 September 1862, going into effect 1 January 1863). Juneteenth commemorates when the Union army arrived in Galveston, Texas, on 19 June 1865 at the end of the American Civil War, and announced that the Emancipation Proclamation had been in effect all along and would now be enforced.

So, Juneteenth doesn't commemorate the end of slavery in the law books; it commemorates slavery actually ending on the ground and people actually going free.

When I reflect on this, it's a very significant difference. Even more, it was a very significant difference at the time - throughout the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in the United States.

You may have heard people say the Civil War wasn't about slavery. There's a bit of truth to that: the North didn't start the war fighting to abolish slavery. In fact, Congress near-unanimously passed a "War Aims Resolution" in July 1861 saying the war was merely "to defend and maintain the supremacy of the Constitution". That was true at the time, and they had many reasons to be fighting for that in particular. First, they needed to keep loyal the slave states still in the Union. But also, even in the North, not many people were actual abolitionists yet. Lincoln and the Republican Party had won a slight majority of the popular vote in the North, but that was on a platform of restricting the growth of slavery rather than abolishing it altogether. Most Northerners didn't want slavery to be allowed in the western territories, largely so that they would be open for small independent farms rather than slave-worked plantations.1 The Republican Party had started as the "Anti-Nebraska Movement" to block slavery from the territories of Kansas and Nebraska; it'd ridden this platform to victory. But most Republican voters, even, didn't oppose slavery existing in the South.

On the other hand the South definitely started the war to protect slavery. They called it "states' rights," but the right they were interested in was the "right" to have slaves. Every state that gave a declaration of secession with reasons said so. As South Carolina put it, "an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the Institution of Slavery has led to a disregard of their obligations."

The war didn't continue like Congress had declared in the heady days of July 1861. Famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass (a former slave himself) had heralded this, supporting Lincoln in the war and saying that his election had broken the power of the slaveholders.

On the one hand, Lincoln himself wanted to do away with slavery - if he could convince himself it was consistent with his "official duty" (as he put it in 1862, with the Emancipation Proclamation written but still sitting in his drawer), but more significantly, if the people would support it.

More significant to changing the goals of the war, though, was the slaves themselves.

Even before the War Aims Resolution, three Virginian slaves who'd been tasked to shore up Confederate defenses - Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory and James Townsend - escaped to the Union lines at Fort Monroe. We don't know exactly what they were thinking, but they figured things would - in whatever way - be better for them even without any official policy. And, they were correct - the Union commander, General Butler, refused to return them. Virginia was calling itself a foreign country, he said, so he didn't need to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act and return escaped slaves, since that only applied to states. Instead, he would be keeping the slaves as "contraband of war," just like any other goods that'd been seized from enemies.

The next day, many other slaves showed up at Fort Monroe. Soon, there was a large "contraband" camp there. A Northern newspaper dubbed it a "stampede."

Official policy soon started to catch up with this. Lincoln happily endorsed General Butler's "contraband" policy, and several months later ordered that any "contrabands" (as they were officially called) who worked for the Army would be paid wages. Eventually Congress specified the Army would not return fugitive slaves, and slaves used for the Confederate war effort would be confiscated. But, what would happen to them wasn't specified. Were they free? Would they be free after the war?

But in practice, they were treated (at least for the present) as free. They were often employed by the Army, and paid for it; and otherwise, they were free to live as they wanted. Regardless of the legal questions, many other slaves rushed to gain what was, on the ground if not in the statute-books, freedom. By the end of the war, there were more than a hundred "contraband" camps across the occupied Confederate states.

Meanwhile, Lincoln was watching public opinion and the progress of the war, and eventually he judged the time right to issue the Emancipation Proclamation: an executive order declaring all slaves in the seceded states free.

When you read the Emancipation Proclamation, it's very dry. It's quite legalistic, emphasizing how it's "a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion." As historian Richard Hofstadter put it, it has "all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading" (that is, a shipping manifest). Lincoln only added one brief phrase about how "this act" is "sincerely believed to be an act of justice."

What's more, next to no one was actually freed on 1 January 1863 when the Proclamation supposedly went into effect. Lincoln had carefully freed slaves in areas that were still in rebellion - still under Confederate control. The slave states that hadn't seceded were left out. Even areas already captured by the Union were left out2, except for a few islands in North and South Carolina. "I can't see what practical good [the Proclamation] can do now," said abolitionist Captain Robert Shaw.

This was done quite intentionally, to try to route around a bigger problem: President Lincoln might not have had the authority to free the slaves at all. He certainly couldn't in peacetime; he justified his Proclamation by calling it "a military necessity" to put down the rebellion. The Proclamation was carefully scoped to make that explanation fit as well as possible, lest some slaveowners from Kentucky or Northern Virginia challenge it in court or in Congress. In the end, nobody did challenge it. In part, that was because it was quickly mooted after the war by the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery across the United States - and that was one reason Lincoln had been pushing for the Amendment.

The Emancipation Proclamation was limited in immediate legal effect, but its impact on the ground during the war was much larger.

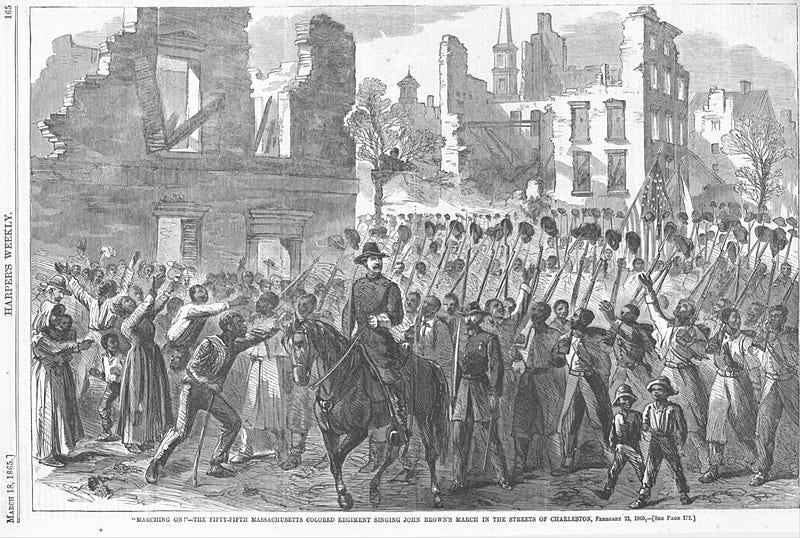

Part of the dry legal language in the Emancipation Proclamation specified that freedmen who volunteered, "of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States". This invitation was enthusiastically taken up. The (segregated) US Colored Troops numbered 175 regiments, with over 178,000 Blacks (whether freedmen or already free before the war) enlisted3. Over 93,000 of them were enrolled under Confederate states, in addition to many credited to Northern states4. It's estimated the US Colored Troops were a tenth of the Union manpower at the time.

It's said that there was never a successful slave revolt in the United States. On the one hand, this neglects the "Black Seminoles" and "Maroon" communities of slaves who'd run to the swamps or to the Seminole Indians, some of whom stayed free till abolition. But on the other and more significant hand, this's because when the government enlisted them in the army, it didn’t count as a "revolt" anymore. The Confederate government insisted on treating captured Black soldiers as escaped slaves trying to stir up a slave rebellion5 - and that's what they were. There were no other slave rebellions during the Civil War because every slave who might've wanted to rebel realized that it was safer and more effective to wait till the Union Army was close enough and then go join them.

Even in the areas left out of the Proclamation, despite all the efforts of the local authorities to hold slaves in their chains, slavery collapsed over 1863 and 1864 both from economic turmoil from the war, and simply because so many slaves were leaving or refusing to work. The Union military authorities in exempted southern Louisiana tried somewhat to hold back the tide, but it was fruitless. Even in Kentucky - well away from the front lines during much of the war, and exempted because it had never seceded - enough slaves were leaving the plantations where they'd been held or just refusing to work.

Of course, this didn't take place all at once. The Union Army marched through the South year by year, bringing liberty to the slaves wherever it went and to those able to reach it from nearby.

As you can see from the map, large areas were only freed in 1865, with the collapse of the Confederacy. Many slaves in places disorganized by the war, like Alabama or Georgia, had already fled anyway. But there were other large areas where the authority of the state government and of the slave-masters had stayed more or less intact through the war.

The largest of those areas was Texas. The Union had attacked a few Texan ports intermittently during the war to help enforce the blockade and cut down on trade with Mexico, but the state had remained largely untouched.

So, Texas was the last place Union troops arrived at the end of the war: June 19, 1865. Then - two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation, and five and a half months before the Thirteenth Amendment finally legally ended slavery in all the United States - on Galveston Island, Major General Gordon Granger landed and proclaimed liberty to all.

A year later, and every year after that, freedmen in Texas organized to celebrate the anniversary of that day. At first they called it "Jubilee Day," or "Emancipation Day", but it later became known as "Juneteenth."

So, Juneteenth celebrates the end6 of the process of emancipation on the ground. The Emancipation Proclamation had said for two and a half years that slaves were now free. Some of them already had been free in reality; gradually over time, more and more of them were. Finally, on that June 19th, people in Texas were too. Or, at least, they soon would be as Union soldiers went from Galveston through the state.

So, when I think of Juneteenth, I think of how slavery wasn't primarily a matter of statute law, but a matter of people actually suffering in real life. And, so, emancipation wasn't just a matter of changing the law (though that very much mattered), but of actually enforcing the new law so that real people would be able to live free. When the freedmen in Texas celebrated Juneteenth - and when Black people in Texas continued to do so afterwards - I think that was why. And that resonates with me too. The reality of history is more complicated than words on a page. We should definitely remember and celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation and Thirteenth Amendment, but it's fitting to have a holiday to celebrate the actual reality of emancipation as well.

One reason for this was that many white people at the time were racist enough not to want Black people living near them, even as slaves. But another reason was that slave plantations would often outcompete free farmers - over time, it was usually cheaper for someone to have slaves working their farm than to hire free workers every year. So, Northern farmers who were thinking of moving west didn't want slaveowners competing with them in the western territories.

Once the seceded states elected new Unionist governments (whether during the Civil War, in the Union-controlled parts of the states; or after the war), those new governments all abolished slavery. Among the states still in the Union, Maryland, Missouri, and West Virginia also abolished slavery by state action during the war; Kentucky and Delaware kept slavery until the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865.

This compares to ~2,100,000 men enlisted in the Union Army throughout the war, though not all of them served at the same time (the peak size of the Union army was 700,000).

In the Civil War, regiments were technically organized under state authority (and counted against state draft quotas) and then accepted by the federal government. A lot of Northern states sent agents down South to enroll freedmen under their state regiments, both for their state honor and to count against their state draft quota. Or, freedmen could enlist in Union regiments raised in the name of their own local states - which is how, for example, South Carolina raised four regiments for the Union.

This also caused the prisoner exchange system to break down. The Confederates refused to exchange Black soldiers, since they considered them escaped slaves. The Union insisted on all soldiers being exchanged equally, so they refused any exchanges until the Confederates changed their minds - which never happened.

At least, Juneteenth marks the end of slavery in the former Confederacy. Slavery would persist in Kentucky and Delaware for another several months until the Thirteenth Amendment.

re: "You may have heard people say the Civil War wasn't about slavery. There's a bit of truth to that . . ."

I'd frame this point a little bit differently. The Civil War WAS about slavery. The articles of secession are very clear on this; so is Lincoln's second inaugural. The claim that the Civil War "wasn't about slavery" typically emerges from or reflects various theories of Confederate apology.

But it's true that the Civil War was about slavery, NOT abolition. It ended with abolition but was neither started nor particularly waged by abolitionists. That's the real distinction these observations point to.

Fascinating summary!