The Thin Line Between Science Fiction and Fantasy

It's a surprisingly hard problem.

The other week, I was talking with one of my friends about the difference between fantasy and science fiction. It's a surprisingly hard problem.

The typical definitions someone might toss off would be that fantasy involves magic and science fiction involves advanced science. The Wikipedia article introductions to the two are along those lines: fantasy "is a genre... involving magical elements, typically set in a fictional universe and usually inspired by mythology and folklore"; science fiction "is a genre... which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology." However, these simplistic definitions break down when you think about them further.

For one simple example, take just about any space opera - any science fiction novel involving travel between stars that doesn't take years. That's almost certainly not possible. You can't travel faster than the speed of light. It'll take you over four years to get to the nearest star, and longer to farther stars. Science can't entirely eliminate some possibilities (like the Alderson drive or wormholes) that might let someone get around this, but they're extremely unlikely.

For an even clearer example, take psychic powers. They're extremely common in Golden Age science fiction - there was a time when many scientists believed they were possible, and one prominent sci-fi magazine editor was an enthusiastic believer. However, this's no longer the case. Psychic powers are about as disproven as they're possible to be. Does this mean that sci-fi stories centered around psychic powers, from Heinlein's Revolt in 2100 to Engdahl's Enchantress from the Stars, are no longer science fiction even though they once were?

But if psychic powers are okay to use in science fiction - what's the difference between that and magic? Orson Scott Card tells about one short story he submitted early in his career to a science-fiction magazine, involving psychic powers on a lost colony with low technology. The colony had lost much of its history, so none of the characters uses the word "psychic" or mentions the long-ago crashed spaceship. The editor rejected the story, saying it wasn't science fiction, and Card should resubmit to a fantasy magazine.1

Let's take several examples that bridge the gap.

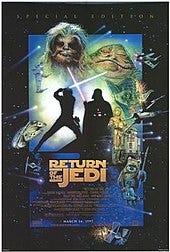

For one, take Star Wars. We all know about the spaceships, hyperdrive, and energy guns; stereotypical technology of science-fiction. However, as Darth Vader puts it, they're "insignificant next to the power of the Force." The Force acts like magic - it can cloud people's minds, lift up a spaceship, predict the future, and even manifest ghosts. We hear later in the prequel that it's linked to "midichlorians," but that merely makes the midichlorians magical.

For another, take Star Trek. Again, we have spaceships and warp drive and energy guns and even more stereotypical science-fiction technology. But along with that, we have aliens who treat spaceships and empires like squabbling children, don't exist in linear time, or even self-identify as the ancient Greek gods. Occasionally, humans can manifest similar powers. These don't act like science; can we say they're magic?

Or from another angle, take Ann McCaffrey's Dragonriders of Pern. It opens like a fantasy novel, with telepathic flying dragons, and with our protagonist magically affecting local plant growth. But, we learn the dragons are genetically modified alien creatures, the magic is psychic powers, and our protagonists eventually end up excavating the lost spaceship that founded their colony. Is this fantasy, or science fiction, or both?

Perhaps someone might be strict about the definition of science fiction and limit it to the actual world and what's actually possible. You could throw out all psychic powers and warp drives and midichlorians. Essentially, this would limit "science fiction" to the hardest of hard science fiction. None of the three examples I gave above would qualify.

However, that leaves a lot of stories that (by this standard) are no longer science fiction. If you say that Revolt in 2100 and Star Trek are no longer science fiction, you need some term to describe them. Perhaps you could say it's a subgenre of fantasy, but then you need some term for that subgenre we currently call "soft science fiction."

In the end, the question is whether it's better to group "soft science fiction" with "hard science fiction" or with "fantasy." For cases where you need to be exacting at science it might be appropriate to group it with fantasy - like, say, engineers or futurists looking for ideas. But for most readers, I believe it's best to group it with hard science fiction.

The previous three examples show the problems there. But there're also other examples bending the genres in another direction.

Take Celestial Matters by Richard Garfinkle, which I wrote about recently. It's about the systematic development and use of technology in a world where Aristotle's physics and Ancient Greek thought is absolutely correct. Our protagonist flies to the sun on a spaceship powered by celestial matter and fed by spontaneous generation. Is he using science or magic? Is this fantasy or science fiction?

Or, take the Mistborn trilogy by Brandon Sanderson. It's a series with unapologetic magic, so called, in an imaginary world. However, Sanderson works out the laws of his magic in detail and has his characters explore and exploit them. By the end of the trilogy, we know the magical use of different metals in his world better than a college chemistry student knows their chemical uses in the real world. Nobody builds large-scale technology with them, but characters absolutely build small-scale devices using magical principles that we the readers can even in many cases predict.

We could go the other way and group everything that claims to be scientific in with science fiction. However, that would quite arguably group Mistborn as science fiction. Its "scientific laws" aren't the laws of our universe, and Sanderson doesn't use the word science. But, his characters do to a large extent use it like science.

To make things even more complicated, fantasy and sci-fi author Marian Zimmer Bradley published a Lord of the Rings fanfic which described several magical objects from that book using technological terms - for example, the fic’s narrator says the Morgul-knives "were fashioned of some manner of high radioactivity." If someone took this as canonical, would it render Lord of the Rings as science fiction? This would be silly. Even if that comment had been written by Tolkien2, reclassifying the entire trilogy based on that one short passage would be silly.

So, we can't define science fiction that broadly, either.

In the end, I think the best division is off vibes. Do things seem to us like they proceed by the rational laws of nature? Or do they seem like they don't? So, scientifically-done psychic powers and warp drives can be science fiction, if they feel enough - to us the readers - like they're scientifically done.

This is inherently a subjective and fuzzy definition. But, genres are inherently fuzzy. There're lots of elements that go into a book, not all of them even intended by the author. I can only rest this definition on my own sense - and on its lining up with how people intuitively see things.

For example, when writing about Celestial Matters, I defended it as being science fiction, because it's exploring the natural laws of its universe in a scientific manner - even though they aren't the same natural laws of our universe. I'd defend Star Trek similarly: it's primarily about technology, and the protagonists approach the Q or wormhole beings or claimed Greek gods using scientific assumptions.

In contrast, Star Wars is primarily themed about the Force (not technology) which is approached in a mystic (not scientific) attitude. Luke Skywalker shouldn't exploit the Force to defeat the Empire; he must surrender himself to it, refuse to exploit the Force, and trust in it to gain victory by being moral. Even if it has some of the trappings of science fiction - even if science fiction stories may be written in the same universe - this is in essence a fantasy story.

This does rest on vibes, and it's totally possible for other people to see things differently. I've seen several libraries and bookstores which avoid this whole issue by shelving fantasy and science fiction together as "speculative fiction," and that makes sense from their perspective. But for myself, and for talking with other people, I think it's useful to distinguish between the genres - and this's how I do so.

I hope it'll be useful for you too and help you explore them better.

Card eventually published the story in his The Worthing Saga, along with other stories set in the same universe. To me, it does read very much like fantasy.

Tolkien never did write anything very like that… though he did comment in a letter that the flying beasts the Nazgul rode could be taken as pterodactyls. Bradley’s fanfic was written before he and his estate took a more negative attitude towards fanfiction.

Let me suggest a different method of classification, one which hinges on the nature of magic. In fairytales, and in the Arthurian cycle, magic is a manifestation of chaos. The antidote to chaos is order. Magic is defeated by an appeal to a higher order. Thus Aslan defeats the White Witch because he knows, and she does not, a higher law. To put it another way, magic is defeated by virtue, a constant theme of the Arthurian cycle. Fairytales, in other words, are about the conflict between chaos and order and magic -- the violation of the natural order -- is the manifestation of chaos. As such, it has no rules.

Science fiction, on the other hand is about competence. The antidote to incompetence is competence, and competence is gained first and foremost by knowledge. Magic, in the Brandon Sanderson sense of the word, is not a manifestation of chaos. It is an alternative physics. Victory comes through the mastery of this alternate physics, not through higher order or virtue.

Which leads us to the question of whether fantasy is on the side of fairy tale or science fiction, and it would seem that today it is more and more on the side of science fiction -- a story with fictional science, rather than a fictional story with real science, but still fundamentally about competence.

Eric Raymond wrote a long essay on SF that implies a distinction similar to yours. It focuses more on SF's political history, but in the middle is a core observation about SF: its tropes are "situated within a knowable universe, one in which scientific inquiry is both the precondition and the principal instrument of creating new futures"... "even when SF is not optimistic, its dystopias and cautionary tales tend to affirm the power of reasoned choices made in a knowable universe; they tell us that it is not through chance or the whim of angry gods that we fail, but through our failure to be intelligent, our failure to use the power of reason and science and engineering prudently".

By ESR's account, a story is SF exactly when it is assuming and affirming a knowable universe. And particularly, when its unknown parts are being explored through scientific inquiry (otherwise it would include too much, such as murder mysteries or certain historical dramas).

http://www.catb.org/~esr/writings/sf-history.html