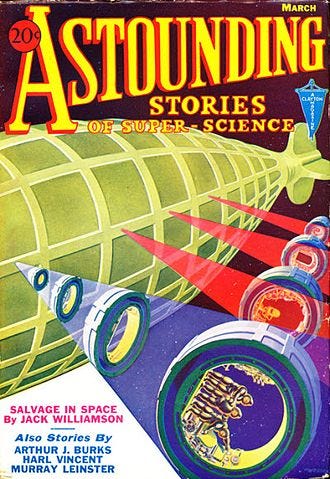

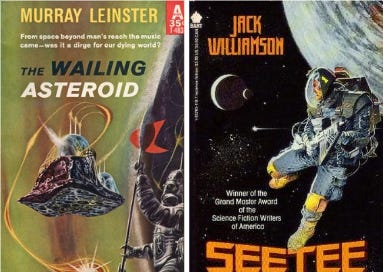

Recently, I enjoyed two science fiction novels from the mid-twentieth-century, the "Golden Age of Science Fiction": The Wailing Asteroid (published 1960) and Seetee Ship (1951). These aren't particularly great books. They're standard-issue plots, with two-dimensional characters and endings that solve things too abruptly. For myself, though, I did enjoy both of them - the plots may be standard-issue for their era, but they were exciting, and I liked the sort of things that happened even though I'd seen similar things before.

After I finished reading these books, I kept thinking about why I'd liked them and other Golden Age science fiction stories - by more famous writers like Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and James Blish - so much. In fact, the flaws in these two novels made some of the common tropes of that age stand out even more and made me realize why I liked them. I don't have any grand pronouncements to make about the Golden Age of Science Fiction, but I've got some observations about some trends which I think could be interesting and helpful to readers.

(As a quick note, it's disputed whether the 1950's were actually part of the "Golden Age of Science Fiction" or a transitional era afterwards; I'll be calling them "Golden Age science fiction" here. That's both for simplicity and because I do consider them part of the same era.)

To briefly tell the plots:

In Wailing Asteroid, an asteroid starts sending out an apparently-automated radio signal to Earth. It's clearly an alien device. Governments frantically try to get a mission together to look into it. Meanwhile, our protagonist - a lone engineer and factory-owner - observes that he's heard the same signal before in some surprisingly detailed dreams earlier. On a guess, he starts building a spaceship with some plans from those dreams. It works. He and his fellow-protagonists reach the asteroid first, to discover it was a war base for ancient aliens and their human servants. The dreams came from a hypnoteaching device, one instance of which had been left on Earth in the distant past. The enemy is about to return and destroy Earth; our protagonists must use this war base to save the day.

In Seetee Ship, our protagonist and his father are small-scale prospectors and settlers in an asteroid belt where a large minority of asteroids are antimatter. ("Seetee", they're called, an in-universe variation of "CT," an abbreviation of an old alternate name for it, "contraterrane matter.") The Belt settlers are groaning under economic and political domination from Earth, and our protagonist hopes to figure out the fabled "Seetee baseplate" problem of how to safely manipulate antimatter and use its near-limitless power. Meanwhile, the Earth government agents are looking into some suspicious circumstances around his father's asteroid... which turn out to be an alien ship that might hold the key to the Seetee baseplate problem.

Looking back over the plots, what stands out to me the most is that they're optimistic. I don't necessarily mean they believe in a good future - definitely not from our perspective (many of these novels have oppressive regimes in the setting), but not even from an in-world perspective either. Our protagonists are frequently upset at what's going on. What I mean is they believe in possibility. The characters feel they have individual agency. They're not resigned to things going negatively. Our protagonist in Seetee Ship isn't necessarily convinced he can solve the "seetee baseplate" problem which has stumped human scientists for generations, but he believes it's possible enough that he's ready to try. And, through unexpected help, it works. This sense that any problem is potentially solvable pervades the genre. In Heinlein's Red Planet (1949), our young protagonists end up launching a revolution themselves, because they've moved forward without being stopped by calling it impossible.

These solutions usually come through science and technology. In Seetee Ship, the limitless power of antimatter is how our protagonist hopes to bring prosperity to the people in the asteroid belt - yet he must figure out how to safely manipulate it first. In Wailing Asteroid, the problems arise during the course of the narrative, but our protagonists must still figure out the secrets of the ancient aliens' technology in order to solve the mystery of their spaceship and save Earth.

The books don't show the actual science in detail. Wailing Asteroid gets away with a few handwaves all around, and for all that Seetee Ship handles the science of antimatter in detail, it also handwaves the gravity generators. Sometimes the technology - or at least the first example of it - comes wholesale from aliens, as we see with Wailing Asteroid, and some parts of Seetee Ship and Heinlein's Farmer in the Sky (1950). Still, with their characteristic optimism and ingenuity, our protagonists start using that alien technology confident that it can at some point be reverse-engineered. In fact, that's the note on which Seetee Ship ends.

The other point - aside from that optimism and ingenuity - is that Golden Age sci-fi tends to assume the audience is excited by science. Heinlein can interrupt Rolling Stones (1952) for lectures in ballistic trajectories, confident that his audience will follow with interest. The solution to the climaxes for both Wailing Asteroid and Seetee Ship depend on our protagonists remembering and applying a scientific theory to their circumstances. Even though they're using alien technology, the science is still their own. And also, even though most of the specific technology was designed and built offstage, this plot-important bit of the science is visible to the readers.

On the other hand, that plot-important bit of science in Seetee Ship is flat-out wrong.

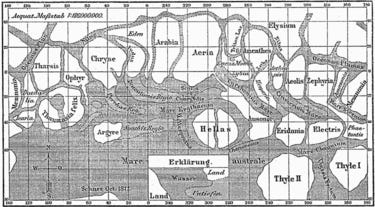

This isn't unique to that one book. Most blatantly, the Martian canals were known to be optical illusions, and Martian life improbable, long before Heinlein gave them major roles in Red Planet. Telepathy, whether mind-to-mind as we see in Red Planet (and many other contemporary novels) or technologically-aided as we see in Wailing Asteroid, is also impossible. The alignment of the Jovian satellites that figures significantly in Farmer in the Sky is impossible because they're in orbital resonance. Beyond that, science has marched on with regards to things like the formation of the asteroid belt and the nature of antimatter. In Seetee Ship and Rolling Stones, it's taken for granted that the asteroid belt was formed by a planet breaking up. Modern science says, rather, the asteroids are parts of the original dust cloud that never coalesced into a planet.

And even beyond this, I'm not sure whether the whole problem of Seetee Ship is scientifically plausible. Our current antimatter manipulation doesn't need any baseplate or any devices made of antimatter. We manipulate tiny quantities of positrons or antiprotons with magnetic fields in particle accelerators, and we use them to generate power by just having them smash into matter, and we can then direct the power just like we can direct the power of nuclear fission (or we could, if it were available in viable quantities). On the other hand, we can direct antiprotons or positrons with electric fields because they have a charge - the antimatter asteroids from Seetee Ship would have no net charge and be much more difficult to manipulate. Perhaps this is the problem?

But regardless, all of this, I just accept as the rules of an alternate universe, a smaller-scale version of the alternate physics that modern writer Greg Egan sometimes writes stories around. The only weirdness is when I'm not sure what rules are used - like in Seetee Ship, where a wrong understanding of antimatter is pulled out of the hat to solve a mystery at the last moment. (In the book it's true, but in the real world it was known false even at the time.) Though even there, I can scarce blame Seetee Ship when it gets so much right - especially as compared to James Blish's The Triumph of Time (1959) where antimatter comes from another universe and simply cannot survive in ours.

Social roles are also very different.

These books were written in the 50's, and it shows. On the larger level, in some places like Heinlein's Have Space Suit Will Travel (1958), we can see an explicit background of small-town America almost indistinguishable from the actual 1950's even while people are flying through space above it. With this in mind, we can place the small factory in Wailing Asteroid as an actual small-town American factory, and we can see where Seetee Ship gets its inspiration for the conflict between independent tradesman/prospectors and the large corporation.

Gender roles are also clearly written in the 1950's. Science fiction writers tended to be on the progressive side, which sometimes (like in Heinlein) leads to a by-now-tropish spunky girl supporting character. In Seetee Ship, this's led to a very interesting place: while the actual women we see on the page clearly have their own beliefs and goals, our characters' social norms around gender relations and romance are just as clearly presuming they won't! This was interesting to read, as a sociological study.

But society isn't the focus of the novels. Sometimes it's hardly present, like in Wailing Asteroid. But even when it's a major theme, like in Tunnel in the Sky or Between Planets, the adventure gets at least as much billing and we have a sense of possibility that even the society can change. And it usually does - either because our protagonists change it through revolution, or because they change their society through emigrating.

It seems to me that these tropes - a sense of limitless possibility, love of ingenuity, and excitement at science and technology - aren't so common in modern science fiction. They definitely exist (I'm immediately thinking of Andy Weir's fun The Martian (2011)) - but they're less common. The 1960's "New Wave" subgenre focused more on symbolism; the more recent cyberpunk and dystopian subgenres put their protagonists in negative social structures usually too complicated for anyone to fully fix.

In part, I'd guess, that's because the cultural mood has shifted. Not so many readers have so much a sense of limitless possibility and excitement at science anymore. The environmentalist movement, and the other movements focusing attention on (often very legitimate!) social problems, probably contributed to this. The space program petering out after the Apollo landings probably didn't help either.

But also in part, I think that's because the science fiction genre has shifted more toward focus on characters and their reaction to the setting they're in. The Stars are Legion (2017) and Sleeping Giants (2016), both of which I've read in the last year, show that well. That was definitely present in earlier novels, and even sometimes the focus - take, for instance, Heinlein's Citizen of the Galaxy (1957) - but it's grown now to the exclusion of these other older tropes.

I definitely like well-developed characters, and if someone prefers them to these older tropes, that's definitely valid. But personally, I'm sorry to see less of the older tropes recently.

That's one reason I plan to keep reading Golden Age science fiction.

I haven't read either of the new books you mention. That's because I've moved more or less exclusively to Indie published (e)books available on Amazon. The sense of optimism / positivity you mention in the golden age books tends to still be there. The characterizations seem to be better though. Or at least they can be, there's plenty of dreck

The one traditional publisher that is still publishing mostly positive books is Baen. A decade or so ago I bought everything Baen published, I no longer do that, but I still buy some books there.

I've been hearing people praise Golden Age SF as optimistic about agency for decades and I find it confusing.

For a man versus environment story like The Martian, it makes sense to say that knowledge and agency is the only thing that matters.

Knowledge and agency are valuable in war, but is any story about war optimistic?

I recently came across a Neil Gaiman essay in which he claims that the moral of 95% of pulp SF is "people are smart. We'll cope." That makes sense for the one story he describes, about an invention that upends everything and the suggestion is that the positive developments are more important than the disruption to people who gambled on obsolete monopolies. This is optimistic. And it takes agency to actually negotiate such a settlement. But this is a very small slice of pulp SF, not 95%, more like 5%. War is where such a negotiation failed.

https://boingboing.net/2014/11/06/neil-gaiman-how-i-learned-to.html

In a zero-sum game like war or racing for a particular discovery, there is conservation of agency. The kids in Red Planet start the war because no one else has agency. Is this optimistic? How about Foundation, where Hari Seldon has agency because everyone else is predictable? In the sense that "it all adds up to normality," it is a positive update to discover that no one else has agency because the world system produces just as much it did before you learned it, but you have more leverage than you thought. But it leaves the mystery of what destroyed everyone else's agency. Maybe you don't have agency, either.

I suppose you could say that Atlas Shrugged is optimistic about war in that it proposes that a system aligned with human agency will defeat one opposed to it. Is the Moon is a Harsh Mistress framed that way? But in that book the Loonies merely preserve their freedom while leaving the Terrans to tyranny. And even Lunar society starts decaying at the end. Does civilization eat agency? That sounds pretty pessimistic to me. Pick your battles is good advice, but whether someone judges it optimistic or pessimistic depends on what they think the heroes should be able to accomplish, which seems pretty arbitrary.

You mention recent dystopias. 1984 is a pessimistic dystopia about a government focused on attacking agency. But recent books like the Giver or The Hunger Games are about individuals overthrowing oppressive governments, aren't they? (I checked wikipedia and it sounds like only book 3 is about revolution, while in the first two the government is pretty good at manipulating the heroine.)

The Stars Are Legion reminds me of the Golden Age story The City and the Stars, a travelogue through a decaying civilization. The characters do not make use of fundamental science, but they gather and exploit knowledge of the artificial environment. Isn't it optimistic about agency? I think there is something else in these stories that you (and many others) are picking up but describing wrong.