The Birth of the Bill of Rights

Even though it was extremely important, the first Congress was left to write the Bill of Rights as amendments to the Constitution. Therein lies a story.

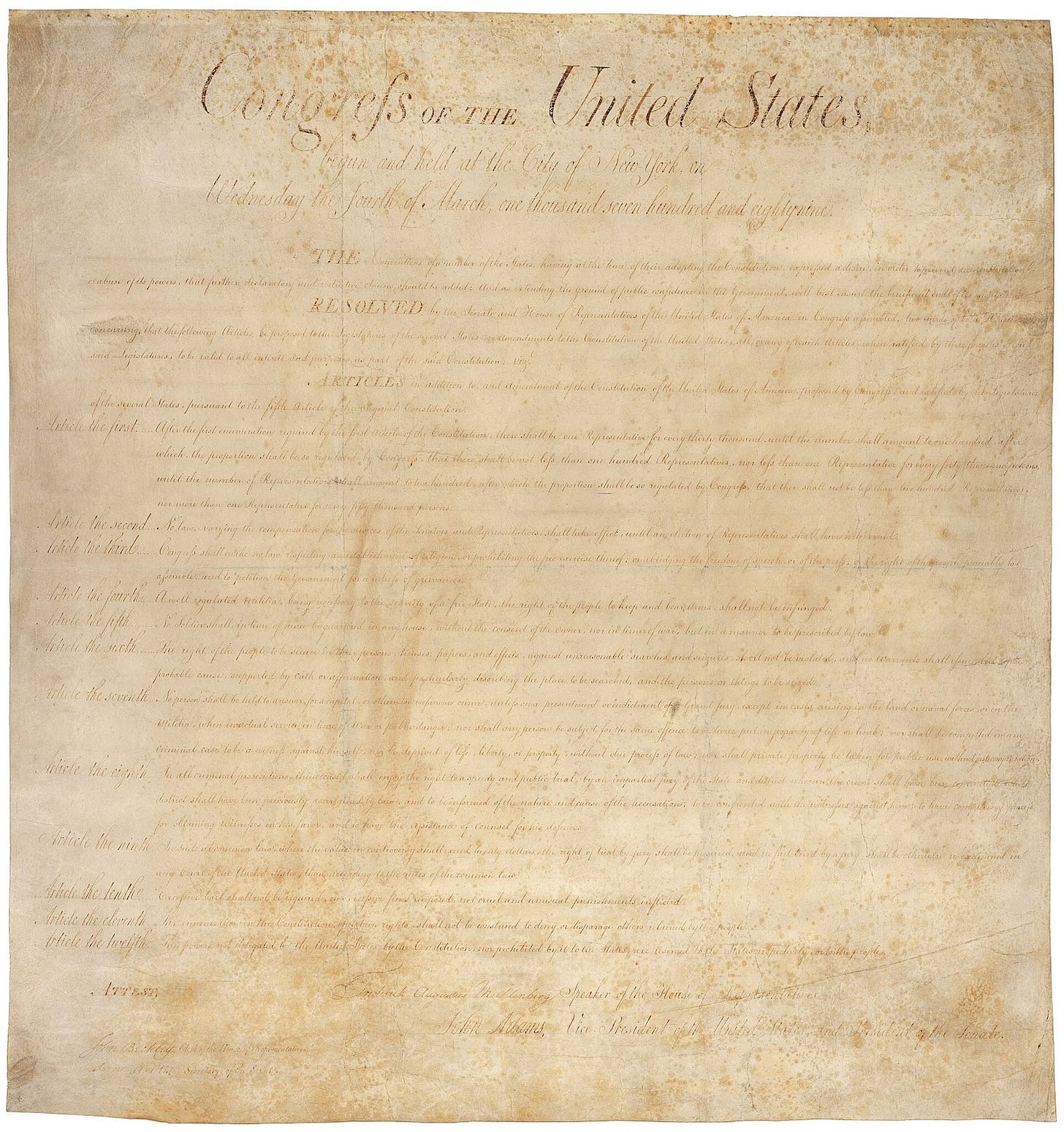

The Bill of Rights

This week in 1789 - September 25th - the US Congress approved the Bill of Rights and sent it out to the states for official ratification. Once ratified by ten states, ten amendments (out of twelve articles approved by Congress) would become part of the Constitution in December 1791. The first ten amendments to the US Constitution, they guarantee many essential rights - to pick a few, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from unreasonable searches, and trial by jury.

Even though the Founding Fathers - and almost all Americans at the time - viewed a bill of rights as extremely important, it wasn't part of the original Constitution. The first Congress was left to write the Bill of Rights as amendments to the Constitution. Therein lies a story.

A bill of rights was already an old thing when America was founded. To pick one example very much on the Founding Fathers' minds, after deposing King James in the Glorious Revolution, Parliament wrote a list of the rights he had infringed on to ensure that they wouldn't be broken again. That became known as the English Bill of Rights.

During the American Revolution, the new American states similarly wrote their own bills of rights, listing a number of rights that George III and the British Parliament had infringed on. But, inspired by political theory, the American states listed more than that: they tried to make comprehensive lists of rights to fence in their new state governments. As John Adams wrote at the start of the (1780) Massachusetts Declaration of Rights, "All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights..." Or, at the start of the (1776) North Carolina Declaration of Rights, "All political power is vested in and derived from the people only."

So, by the end of the Revolution, twelve1 out of the thirteen2 states had a Bill of Rights.

But, the United States itself didn't.

That was because the Articles of Confederation (written 1777-1781) was essentially a treaty among the thirteen states, where "Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence." The Articles "expressly delegated" a few powers to Congress "for the most convenient management of the general interests of the United States", but Congress wasn't given any powers that people thought would let it infringe on people's rights, so no bill of rights was needed on that level.

When the Constitution of 1789 (the same one we have today) was written, despite the federal government being given more powers (and its own sovereignty, casting into doubt the previous framework), the authors didn't think one was necessary either. "The State Declarations of Rights are not repealed by this Constitution," as delegate Roger Sherman objected when someone suggested a bill of rights.

Nevertheless, as the states debated whether to ratify the Constitution, one of the major objections was that it lacked a bill of rights. Eleven states finally did ratify3, "under the conviction, that, whatsoever imperfections may exist in the Constitution, ought rather to be examined in the mode prescribed therein, than to bring the Union into danger by a delay" as Virginia put it. But, many of them strongly recommended a bill of rights lest the new government - with its new powers and separate sovereignty - infringe the people's rights. It would be a government elected by the people, but they still weren't willing to trust it.

When Congress first assembled under the new Constitution in March 1789, it was very busy setting up the new government and writing urgent laws, but James Madison of Virginia - coauthor of the Federalist Papers that helped secure ratification for the Constitution - eventually proposed a Bill of Rights. There was long debate; some objected to any amendments so soon; others like Representative Theodore Sedgwick (of Massachusetts) argued that it was impossible to list out all important rights; a worthwhile Bill of Rights would need to include rights such as "that a man should have a right to wear his hat if he pleased; that he might get up when he pleased, and go to bed when he thought proper."4

Roger Sherman (now a Representative) persuaded the House to add the amendments to the end of the Constitution rather than editing the text, setting a precedent followed by every amendment since. This helps us understand the historical growth of the Constitution, by seeing at a glance which parts were adopted when.

Twelve amendments (out of Madison's original nineteen) passed Congress, on 25 September 1789. According to the Constitution, three-fourths of the states were needed to ratify them. By 15 December 1791, ten of those twelve amendments5 were ratified by eleven of the fourteen states6 to become the first ten amendments of our current Constitution, what we know as the Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights guarantees many vital rights. In everyday life, there're the right to freedom of speech, of religion, and of assembly; the right to bear arms; the right to not have soldiers quartered in your house; the right to not have your property unreasonably searched; and others - some of which Britain had violated before the Revolution; others it had been feared Britain might violate. In court processes, there're the right to trial by jury, to not be unreasonably or cruelly and unusually punished, to be able to call witnesses in your defense, to have a speedy trial, and others - again, many of which Britain had sometimes violated. And then, finally, it acknowledges there're other rights too; and says that the powers not given to the federal government are retained by the states and people.

The Bill of Rights doesn't claim it gives us rights.

Instead, it says, "Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom of speech." Most of the other rights use the same phrasing. For example, the freedom of speech already exists; the First Amendment bans Congress from violating it. We already had our rights before the United States or its Constitution existed; the Bill of Rights is recognizing that. As law professor Randy Barnett puts it, "First come rights, and then comes government." That, he says, is the fundamental substance of "the American Theory of Government."

In the words of the Ninth Amendment, the Bill of Rights is merely "the enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights..." There are other rights that also already existed before the Constitution; the Ninth Amendment continues by saying this enumeration "... shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." There were already thirteen state Bills of Rights with different lists of rights; Congress wasn't trying to make one authoritative list of every right. They knew there were others they weren't listing, even down to things as simple as Sedgwick's "right to wear his hat if he pleased."

Nowadays, most Americans usually think of the Bill of Rights as something where lawyers argue in court over the exact bounds of each right, and something that's enforced by the courts by overturning laws that infringe on it.

None of this was in the minds of the Founding Fathers.

Hamilton, in the Federalist Papers, considered the courts to have more "natural feebleness" than any other part of government, and to be "in continual jeopardy of being overpowered, awed, or influenced." For decades, the courts bore him out. The Supreme Court didn't find any federal law to violate the Bill of Rights until Dred Scott, where they claimed the Fifth Amendment forbade the government from freeing slaves in federal territories.

In the dispute over the Sedition Act in the 1790's, when the federal government briefly made it illegal to criticize them, people barely considered challenging the act in court. Jefferson and Madison did argue (among other things) that the Sedition Act contradicted the United States Bill of Rights - but they cited other bills of rights in the same breath, rather than attaching sole significance to the precise wording of the First Amendment. And, they did so in state legislative resolutions and in the press rather than in the courts.

Instead, the Bill of Rights was foremost - like other bills of rights - meant primarily as a rallying place. It was meant to guide Congress and the President as much as the courts, and - at least as importantly - to remind every American these are our rights.

The exception was Rhode Island, which still kept its old colonial charter rather than writing a new Constitution. That’s a story in itself, which I hope to write here someday.

Or, thirteen out of fourteen, if you count the unrecognized Vermont Republic which also had a Bill of Rights.

The exceptions were North Carolina (which eventually joined the already-started government on 21 November 1789) and Rhode Island (joined on 29 May 1790).

As a comic sidenote, ever since 1837, you have not had the right to wear a hat in the gallery of Congress. I first saw this on my ticket when I toured the Capitol, and ever since, I’ve considered it a sign of how we have, in fact, needed to list out our rights lest the government infringe them.

Of the other two amendments, one of them regulated the size of the House of Representatives, and is technically still pending for states to ratify; the other prohibits Congress from voting itself immediate pay raises, and eventually got ratified in 1992 as the 27th Amendment.

On 25 September 1789, there were eleven states, so nine states were needed to ratify. By December 1791, North Carolina and Rhode Island had finally ratified the Constitution (in part thanks to the Bill of Rights being proposed, and in part thanks to Congress threatening tariffs against them); and the Vermont Republic had also been admitted thanks to New York dropping its claim to the land. So, by that time two years later, 11 states were needed to ratify a Constitutional amendment.

Great post!

After reading Woody Holton's 'Unruly Americans and the Birth of the US Constitution I was left with the impression that the US Constitution was born from a meeting of the governing class of the US.

The Congressional Congress was in debt to its governing class, so they could not welsh on the debt.

The debt was in specie, gold and silver, so they could not print money. Everyone knew US printed money was not worth a Continental Dollar.

They tried taxing everyone for gold and silver. 90% plus Americans were dirt farmers, no gold or silver, just land they'd move off and go west anytime. They tried taxing dirt farmers and got Shay's Rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion, farmers going in a body to the state legislature to veto enforcement of taxes, tax collectors going to debtor's prison because they could not collect taxes, farms seized from farmers who lit out west and left neighbors laying in the bushes to backshoot whoever bought the farms ... After that and worse, dirt farms still had no gold and silver.

So the governing class got together and made a Constitution that said taxes would be collected by tariffs at ports where the gold and silver was.

But by then they'd annoyed the dirt farmers, who made them accept a BIll of Rights to keep tax farmers from messing with them.

Every economist on Earth hates tariffs. A tax on the consumers! A subsidy for local manufacturers! Bad!

All true, but the US manufacturers were in New England, which was seriously considering secession from the other buttholes in the US 1776 - War of 1812. New England had a good war of the Revolution. The Brits won the Battle of Bunker Hill, lost half their army, stayed in Boston. Nobody crossed the Brits in Boston with an army and British battleships. Afterwards Boston merchants repaid the Tories 5 million pounds and kept doing business. The South repaid nothing and stopped doing business with Brits. Why?

Everyone in the South had a horrible eight years total war with Brits raiding everyone. New Jersey had a total war for eight years, New York middling. 1776-1815 was a long time, and the Brits were waiting to pounce the whole time. A subsidy to the governing class of New England to convince them to stay in the Republic was a great idea.

So the tariffs worked. The US Constitution worked. The Bill of Rights worked to placate the dirt farmers because nobody federal sent tax collectors.