This week in 1801, on February 17th, the US Presidential Election of 1800 was finally settled. Thomas Jefferson would be President, in the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing political parties in the United States federal government.

As you can tell from how long it had been since Election Day, the election of 1800 was a mess. It was a mess in several ways, some of which sound surprisingly modern despite the country barely being ten years old at the time. But still - despite all the fears of people at the time, what actually transpired was nothing like what either side had feared. More than that, it was a triumph: the first transfer of power between opposing parties in the United States.

In short: Thomas Jefferson, who'd essentially founded the brand new Republican Party1, was facing off against incumbent John Adams of the Federalist Party. The Federalists had essentially held power since the federal government was formed. Both sides fought a highly-vituperative campaign with multiple political machinations. Finally, the Republicans won in the electoral college (there wasn't really a popular vote)2 - except that, at the time, the Constitution didn't provide for separate Presidential and Vice-Presidential ballots, so Jefferson and his own Vice-Presidential nominee, Aaron Burr, were technically both running for President and tied each other. To cap off the mess, the lame-duck Federalist House of Representatives had to break the tie, and they took until 17 February to do that (during which time some people were plotting to keep a Federalist in office).

But in the end, the House did vote for Jefferson, and he took office peacefully and smoothly.

I think this's a fascinating story, and one that can provide some perspective to people following modern-day politics.

The original cause of this mess was that nobody had realized the United States would even have political parties. The thirteen states3 didn't have them, and many didn't even have at-all-organized factions. "Factions," all the Founding Fathers agreed, were a bad thing, and fortunately usually a temporary thing. In the Federalist Papers - written to support the new Constitution of 1789, the same Constitution we have today - they talked about how the sheer size of the United States would stop any factions from arising on the Federal level. They designed the Constitution assuming that politicians would be independent from each other, working either for their self-interest or their own constituents' interest.

But, parties showed up anyway. Almost as soon as the first President, George Washington, began taking any meaningful actions, some people in Congress supported what he was doing, and other people opposed it. The people who opposed it, like Secretary of State Jefferson, started collecting a temporary alliance - in "the republican interest," as one of Jefferson's allies called it - to rescue the United States from the would-be aristocrats who were supporting the administration; they dubbed themselves Republicans. And then, the people who supported Washington, like Vice-President Adams and Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton, started banding together in what they also called a temporary alliance to oppose the Jacobin anarchists trying to tear down the government; they dubbed themselves Federalists. So, even though President Washington deplored factions and tried to hold himself above the fray, the Federalists had essentially held power from the start of the federal government till 1800.

Looking back, we see that the Federalists generally wanted a stronger central government and favored merchants and industrialists and cities. The Republicans generally wanted a weaker central government (and stronger states) and favored farmers and "the common man." In addition, in the French Revolutionary wars which were going on, the Republicans favored France while the Federalists favored Britain - though how strongly varied over time for both sides. A lot could be said about these differences, but I think they aren't the most important part of this story, and they definitely weren't what the two sides focused on at the time.

At the time, they both saw each other in apocalyptic terms. They didn't view each other as just disagreeing on policy; they each thought the other party was opposing America. To their partial credit, the whole concept of organized political parties disagreeing with each other was new. America was new. The last major factional disagreements - with the Anti-Federalists opposing the Constitution twelve years before, and before then with the Tories opposing the American Revolution twenty years before - really had been that foundational. But to quote one handbill from 1796, in language that fit the American Revolution more than party politics:

Thomas Jefferson first framed the sacred political sentence that all men are born equal. John Adams says this is all farce and falsehood; that some men should be born Kings, and some should be born Nobles. Which of these, freemen of Pennsylvania, will you have for your President?"

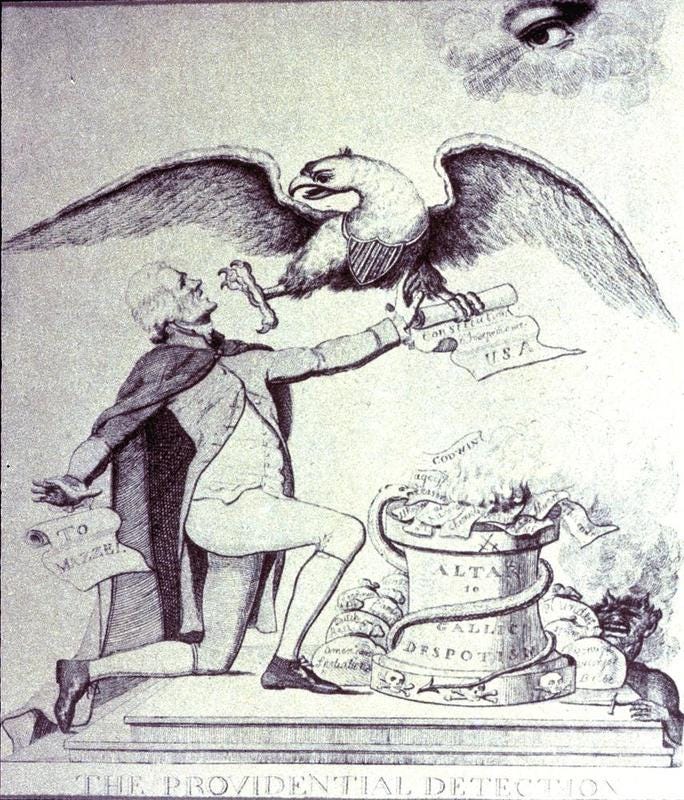

Believe it or not, this was typical rhetoric. Another Republican article made up, in detail, a story about how Adams was plotting to marry his son to a British princess and establish a royal dynasty. The Federalists replied in kind; they accused Jefferson of planning to welcome a French Revolutionary army, and stated in one handbill that the choice was between "God - and a religious President [or] Jefferson - and no God." As far as I can tell - even in their private letters - both sides really did believe the stakes were this high. Adams privately said during one debate on a commercial treaty that if the Republicans killed it, then "this constitution could not stand."

To all this heated rhetoric and actions, the Federalists responded by the unprecedented and unequaled Sedition Act of 1798. In short, it made it a crime to falsely criticize the government. As the Federalists were in power, that basically meant criticizing the Federalists. Among other prominent prosecutions, Congressman Matthew Lyon of Vermont was fined and imprisoned for accusing Adams of "ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice." This was before judicial review (it'd be established in 1803), and the federal courts were Federalist-controlled anyway, so nobody seriously considered solving the problem there. Instead in response, as if trying for just as wild legal schemes as the Federalists, the Republican-controlled Virginia and Kentucky legislatures passed resolutions nullifying the Sedition Act: declaring it unconstitutional and unenforceable in their states.

(Fortunately, the Sedition Act expired just after Jefferson's inauguration. He pardoned everyone who'd been convicted under it, calling it "a nullity as absolute and palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image.")

Jefferson and Adams had faced off once before in the election of 1796 (Adams had won). Going into 1800, they were still the logical candidates of their respective parties. Both prepared for it to be a hard battle deciding the destiny of America. It was considered unseemly for candidates to personally campaign, so the campaign meant increased vituperation from both sides.

It also meant political maneuvering. Most significantly, Jefferson chose Aaron Burr of New York as his running mate. Burr, leaning Republican (though New York politics was still more a battle of personalities than parties), had created his own political machine in New York City. Jefferson needed that to gain New York State's votes, and thus the election.

Even more than that, both sides focused on electing their supporters to state legislatures so they could manipulate how the Presidential electors were chosen. Then as it technically still is now, the President was elected by electors chosen in each state however the legislature chose4. In most states, electors were chosen by the legislature. Where they were elected, district versus general-ticket voting was up for grabs - as well as the names of the electors themselves, where both sides tried to choose prominent people (since, unlike today, the electors' names actually appeared on the ballots then). The Republicans got Virginia's electors chosen by the people on a statewide vote (like today5); the Federalists won New Jersey through gerrymandering the legislature which then chose electors itself; in Pennsylvania each side won one house of the legislature and fought out a showdown until they eventually agreed to split and name eight Republican and seven Federalist electors.

Everyone back then expected schemes like those, testing out the boundaries of the Constitution that was just twelve years old. After that, things settled down to a more accustomed set of political norms. More recently... I don't plan to speak about modern political maneuvering, but a lot of the schemes I've heard in the modern press are familiar from what I've read about people trying or floating in history.

After all those political machinations and campaigning, the Republicans - Jefferson and Burr - won a 73-65 majority in the Electoral College. Losing New York or South Carolina or their half of Pennsylvania would've lost it for them.

Except - as I mentioned before, Burr was technically running for President too; he and Jefferson tied. According to the original Constitution, each elector voted for two people for President. If two people both got a vote from the majority of electors, the one with the highest majority would become President and the one with the next-highest would become Vice-President. The Framers hadn't envisioned political parties, so they assumed that hardly anyone would ever get a majority. After all, they said, the United States was so big that not that many people would be nationally famous. So, if no one got a majority, the House of Representatives (voting by state) would decide the President from the top five candidates. Or if two people had an equal majority, the House would decide between the two of them. In essence, the Framers thought, the electors would usually be nominating candidates for the House to choose the President from6.

The Federalists performed perfectly under this system: all Federalist electors cast one of their Presidential votes for Adams, and their second vote for Charles Pickney; except that one elector threw away his second vote on John Jay. So, if the Federalists had won a majority, Adams would've been the top candidate and become President; Pickney would've been the runner-up and become Vice-President. But, because of Burr's jealousy and fears that some electors would be "faithless" and choose someone else of their own choice, the Republicans had instructed every elector to vote for Jefferson and Burr. Unexpectedly, no one proved faithless. Jefferson and Burr were tied. The tie needed to be broken by the House... the lame-duck Federalist-controlled House.

Many Federalists were inclined to make a deal with Burr, or support him as President anyway. Burr had rarely denounced them or their principles; he was a man of New York politics which was still more a matter of personalities. In addition, he was hardly ever one to talk about grand political principles at all. Burr did seem to at least be open to this plan. We don't know that he actively cooperated with it, and he did refuse to go to the Federal City (as Washington, DC, was called then) in person to help convince wavering Congressmen. But, he didn't categorically refuse. Jefferson never trusted him afterwards.

Meanwhile, another prominent Federalist - Alexander Hamilton - pressed his party to support Jefferson. Burr, he said, "has no principle, public or private"; "his ambition aims at nothing short of permanent power and wealth in his own person." Jefferson, by contrast, would be "the least of two evils."

Hamilton had already been Burr's enemy in New York politics. But I do have to say that Burr is closer to fitting his accusations than anyone else in early American politics. We do know is that later, while Vice-President, he actually raised his own private army. He was accused of treason for that (I might tell that tale in another post soon) (EDIT: Here it is!). I'm not sure whether he was actually planning treason. But when the Federalists accused Jefferson, or the Republicans Adams or Hamilton, of wanting to become a dictator - I laugh it off knowing that their actions and private papers prove otherwise. But when Hamilton accuses Burr... Burr is enough of an enigma that I don't have that proof. Lin-Manuel Miranda's musical caught a big aspect of Burr's character when it had him advise "Talk less; smile more; don't let them know what you're against or what you're for."

Meanwhile, Republicans discussed plans to openly levy war if the Federalists tried to hold onto power. It was a possibility; the Constitution didn't say what would happen if the House didn't choose a President by Inauguration Day. It would've been warranted if their rhetoric about the Federalists wanting to establish a monarchy had been true - and the Republicans really did think it was true. A few Federalists, terrified that the Republicans would be anarchists, were actually cooking up schemes to do this.

But thankfully, neither side actually put its anti-apocalypse plans into action. The worst thing the Federalists actually did was to pass a new Judiciary Act establishing new courts, to which President Adams named Federalist judges... also naming his Secretary of State John Marshall to the Supreme Court, where Marshall would have great impact later.

Amid all these apocalyptic plans and rising tensions, Congress finally met on February 11th to count ballots and for the House to choose. A majority of state delegations - nine of the sixteen states - were needed. (Each state's vote was a majority of its delegation.) On the first ballot on February 11th, Jefferson got 8 states (where Republicans had a majority), Burr 6 (where Federalists had a majority), and two states were evenly-divided and thus not counted. So they continued throughout the week, waiting for who would blink first, while tensions continued to rise even further and the (Republican) Governor of Pennsylvania marshaled his militia just in case. Finally, after a week - on February 17th - and hearing assurances that Jefferson would not dismiss all Federalists from the civil service, enough Federalists gave in. By 10 states to 4 with two abstaining, Jefferson was elected President.

At the end of this mess, Jefferson was duly and peacefully inaugurated on 4 March 1801. Adams had left town the previous night on the public stagecoach; Jefferson - dressed as a common citizen - walked to the Capitol and took the oath of office from Chief Justice Marshall. For all the apocalyptic rhetoric, things worked out. The Federalists weren't aristocrats thwarting the people's will; the Republicans weren't anarchists trying to tear down the government. Jefferson said in his inaugural address, quite correctly, "The contest of opinion... being now decided by the voice of the nation, announced according to the rules of the Constitution, all will, of course, arrange themselves under the will of the law, and unite in common efforts for the common good."

It was very optimistic for Jefferson to say "of course" there. But in fact, despite all the boiling rhetoric, his hopes did come true for a while.

What's more, partisan strife almost vanished. The Federalist Party largely melted away; Jefferson won reelection four years later carrying every state except Connecticut and Delaware. By the time new political parties emerged in the 1820's, the rhetoric was less heated as a new generation accepted parties as an inherent part of American life, and both parties accepted each other's loyalty to America. That would eventually temporarily break down in the 1850's with the new antislavery Republican Party... but that's another story, which maybe I'll tell in another post.

(And then political rhetoric has become heated again in the modern day, but that's also another story, and one I don't plan to write on this blog.)

I could say a lot about the political consequences of the election of 1800, how Jefferson's vision of America wrote itself into our self-conception, and how some Federalist policies stayed around anyway. But the more significant thing is that this established a precedent for political parties fiercely fighting elections but then giving in after losing, trusting that their fears would be proven groundless - and also, a precedent for the victorious party not living down to its opponents' rhetoric. Sometimes we lose sight of this because it's gone without saying for so long. Sometimes I do myself - but then I look at history, and our modern-day fears take on a new light in perspective.

In 1800 and 1801, the American republican government passed its second great test. The first test was when the first President, George Washington, abided by the Constitution and stepped down from office; the second test was when President Adams left office in favor of his political enemy after losing an election. "I have repeatedly laid myself under the most serious obligations to support the Constitution," Adams had said in his inaugural address - and he acted that out by leaving office. Despite everyone's rhetoric, he - just like everyone else on both sides - valued the Constitution more than he feared anything his opponents might do.

The United States would be a very different place if they hadn't.

There's no direct relation to the modern Republican Party, which originated in 1854 as an antislavery movement. Some historians call Jefferson's party the "Democratic-Republican Party," a name that some of them occasionally used at the time; but the normal contemporary name was "Republican Party."

There wasn't a full popular vote. Six of the sixteen states chose electors by popular vote; the Republicans won them in a landslide. The other ten states had their legislatures choose electors, so we don't know how a full popular vote would have gone.

Fourteen, if you count the unrecognized Vermont Republic which didn't have political parties either. (Vermont became a state in 1791, during President Washington's first term, after New York gave up its claim to the land.)

Now, of course, all state legislatures have enacted that the people will choose the electors by popular vote. The last state to consistently choose electors in its legislature was South Carolina, through the 1860 US (and 1861 Confederate) Presidential elections. After that, the Colorado legislature chose its electors once in 1876, when it gained statehood without enough time to arrange a popular election. In 2000, Florida attempted to do so after the election while the results were being debated in court; both the legislature and court-finalized recounts chose the Bush/Cheney electors, so their attempt ended up not mattering.

Technically, like today in 48 of the 50 states. Nebraska and Maine choose two electors by statewide vote, and the others by district vote. But today, unlike in 1800, we don't see the electors' names - they're listed as "Electors for (candidate's name)".

In 1804, as a consequence of this mess in 1801, the Twelfth Amendment would change this all to the current system. Since then, the electors cast separate ballots for President and Vice-President. If no Presidential candidate gets a majority, the House (still voting by states) decides from the top three. Under this system, the House has needed to vote on the President exactly once, in 1824, though some modern third-party candidates have tried to trigger it again.