The Battle of Lexington and Concord

"Here once the embattled farmers stood, and fired the shot heard round the world."

This continues my series marking the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the American Revolution. Previously was Liberty or Death: the Last Speech Before War, on 22 March 1775; next is The Growing War and the Continental Congress, on 10 May 1775.

The anniversary here is properly next week, 19 April, but - partly following medieval Christian traditions about two commemorations occurring on the same day - this is bumped in favor of Holy Week.

The bells were rung the drums were beat

The Melitia attended the roll

Every face we meet in the street

Wears a determined Scoul

For this is the day all men expected

Yet none of us wanted to see

But now it had come no one rejected

Our Country’s call for Liberty-- Ebenezer Stiles, "Story of the Battle of Concord and Lexington", 1795

Next week in 1775, the American Revolution broke out into war.

Everyone in Massachusetts had known this was coming since the previous fall, when the Patriots formed their own government and started drilling as militia. General Gage had been too terrified to send his troops too far out of Boston...

... But King George and his Cabinet had sent Gage peremptory orders to suppress the rebellion with the troops he had, or be held a coward.

So, Gage laid his plans to follow his orders the best he could. He would send a column of about 700 soldiers to Concord, where his spies had told him the Patriots had a large supply of gunpowder. They would leave overnight, ferrying to Charlestown, hopefully reaching Concord before dawn and before any Patriots spotted them. And on the way, they would march through Lexington and hopefully capture Samuel Adams and other Patriot leaders who were known to be there.

This was an optimistic plan, but perhaps the best that could be done in Gage's situation. He'd delayed this long, but with his new orders, he no longer could.

The plan immediately started going wrong.

Boston Patriots had seen the troops preparing. Joseph Warren (soon to be President of Massachusetts) chose Paul Revere and William Dawes - two staunch Patriots, of whom Revere had previously carried other important messages - to spread the alarm, to Concord and everywhere along the way, as soon as the troops were leaving. Revere would go by sea; Dawes by land over Boston Neck.

Revere rowed to Charlestown well ahead of the Redcoats. They had too few boats, and the boats they had ill-prepared. He spread the alarm to every town on his way. Contrary to popular belief, he did not shout "The British are coming"; the Patriots of Massachusetts still considered themselves British. What he actually cried was "The Regulars are coming out!"

Revere reached Lexington a little after midnight (Dawes around 1 AM). Adams, already elected a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, was there; along with John Hancock, the president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and thus the closest thing to Massachusetts' chief executive. Hancock insisted on personally joining the militia who were starting to assemble on Lexington Green. Adams was horrified, and he and Revere eventually talked Hancock down. Then, after some time discussing plans, Revere and Dawes - now accompanied by Dr. Samuel Prescott, a Patriot who'd met them in Lexington - rode on to Concord.

But by now, the Redcoats' scouts (a few hours ahead of the main column) were already there. About halfway to Concord, the three of them were halted by six Redcoats.

Dawes instantly turned back to Lexington and escaped; Prescott sped off into a field and escaped to warn Concord; Revere stood his ground and was captured. As they took him back toward Lexington and the approaching column of Redcoats, he insisted to his captors that at least five hundred militiamen were already on Lexington Green and about to destroy the Regular column. They believed him, and headed back in fear to warn the main column taking Revere with them - but, upon hearing some gunshots while passing Lexington, they released Revere and galloped away.

Revere ran into Lexington (the Redcoats having kept his horse) and convinced Hancock and Adams to leave at once. But, encumbered by a trunk full of secret records, they were delayed until battle was already joined across town.

The Lexington militia, or those who could come in the middle of the night, had assembled. Revere had wildly exaggerated; there were perhaps seventy or eighty of them. They were led by Captain John Parker, a local farmer, veteran of the French and Indian War, and committed Patriot, already ill with the tuberculosis which would kill him that next September. But at the moment, he was ready to lead his neighbors.

Parker didn't want to start a war right then. Even if he wanted a war, he knew his men weren't ready that dawn. But, he didn't know what the British would do. In the end, he ordered his militia not to "meddle or make with said Regular Troops (if they should approach) unless they should insult or molest us", but kept them there on the Green.

And then, at sunrise (5 AM), the lead column of Regulars under Major Pitcairn marched into town.

For a while on Lexington Green, the Regulars and the militia stood there facing each other down. Captain John Parker and his militiamen did not want to be the first to open fire. They weren't soldiers; they were normal farmers from the town of Lexington who'd been drilling as militia for the day when they'd be needed. But they didn't want to start the war if it could be delayed.

After a bit - as, unknown to any of them, Revere and Hancock and Adams were still struggling away with the chest of important papers - Parker ordered his militia to disperse.

But then, a shot rang out.

Nobody knows who fired that first shot. Pitcairn and his officers blamed the militia; Captain Parker and his men blamed the Regulars. But both sides quickly returned fire at each other. The war had begun that morning in Lexington Green. Eight militiamen were killed, and one Regular injured: the first deaths in battle of the American Revolution.

Parker and his militia, outnumbered and unready for a stand-up battle, quickly retreated to the fields around the town. The Regulars, enraged, chased them down until the rest of the column arrived and Lieutenant Colonel Smith stopped them. Under Smith's command, they continued to Concord - but news was outpacing them. Already between Lexington and Concord, a few militiamen fired at the Regulars from the hills.

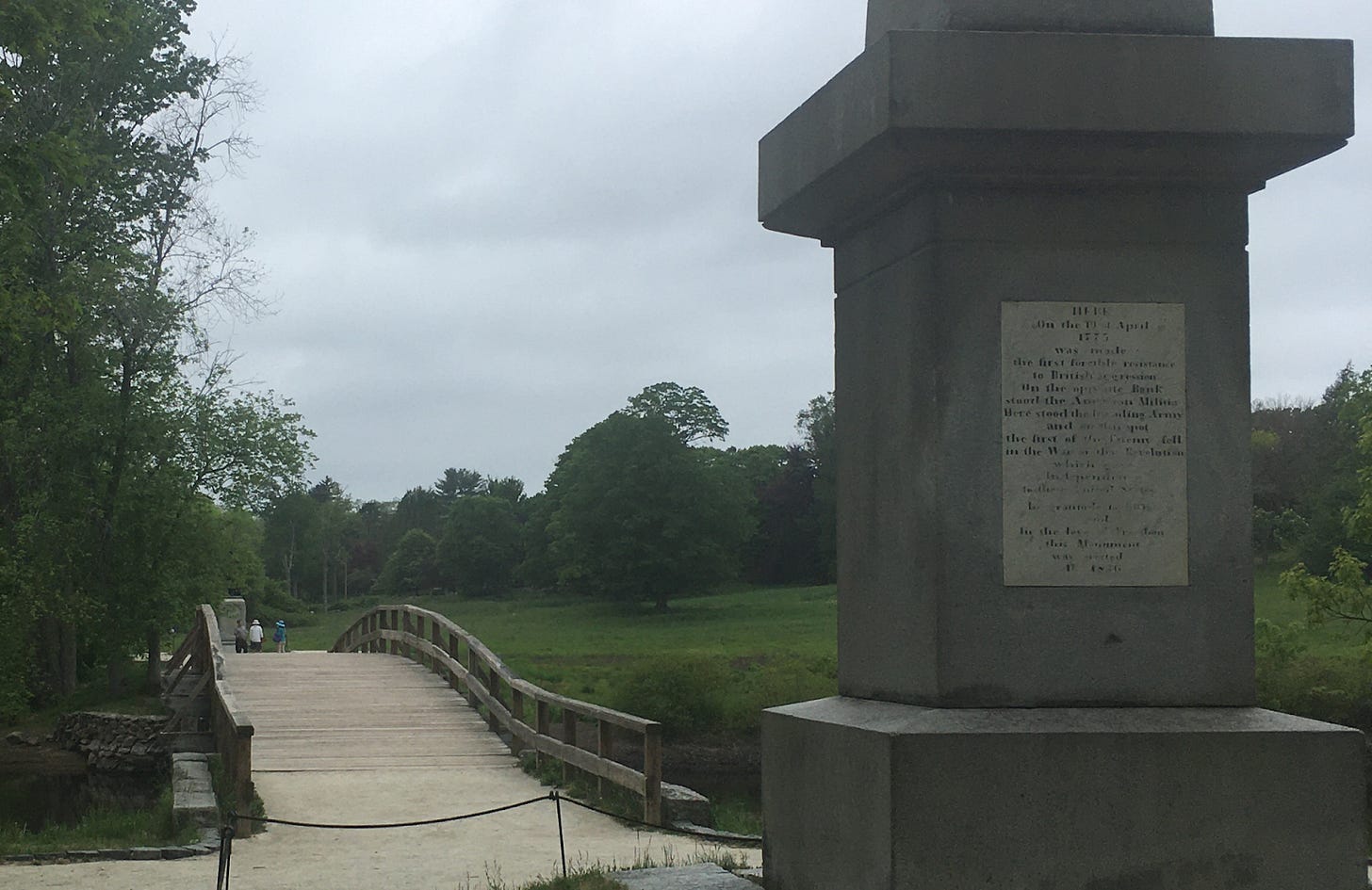

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard round the world.-- Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Concord Hymn," 1837

Prescott had completed Revere's mission for him: he'd alerted Concord.

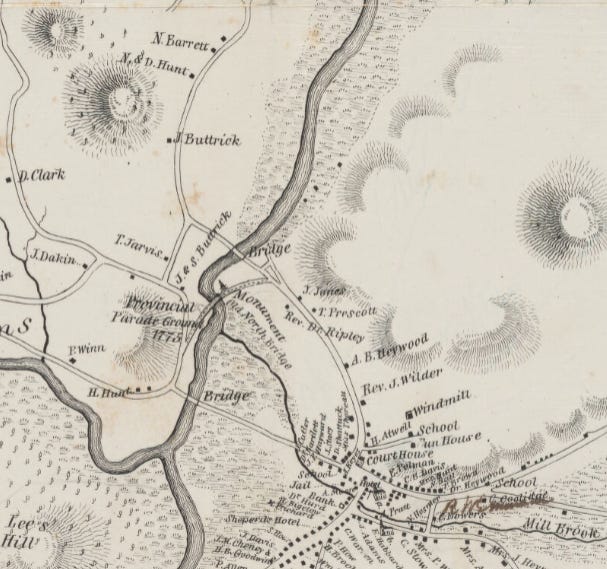

The militia of Concord, or those who could come overnight, assembled under their leader, Colonel James Barrett. Like Parker, he was a local farmer and veteran of the French and Indian War. They rushed to hide the supplies and prepare for possible war, as news reached them that the possible had turned actual. Men from nearby towns - Lincoln and Bedford and Groton - joined them overnight, bringing their numbers to around 250. Barrett, not knowing the enemy's numbers, ordered his men to wait at Punkatasset Hill on the far side of town and not fire the first shot under any circumstances. Most of the town's residents also fled westward.

The Regulars - the full 700 of them - marched into town around 7:30 AM, searched the town, found little (because most of the supplies had already been hidden in farms on the far side of town), and took their time destroying what they could. They knew Barrett's militia was on the edge of town, but they didn't take much care.

Smith sent about a hundred troops across the North Bridge toward Punkatesset Hill (and Barrett's own farm) to search the nearby farms for hidden supplies. Some of the militia wanted to confront them right then and there, but Barrett ordered them to wait. He was wise: more reinforcements arrived, swelling their numbers to around 400, while the Regulars retreated to the bridge lest they be cut off. But then - around 9:30 AM - the militia saw smoke rising from the village square. The Regulars were burning weapons - but it looked like they were burning the village. Some men demanded whether Barrett was going to let the Regulars burn the village down.

At that, Barrett ordered one company (which had volunteered) to advance down to the North Bridge. The British guard at the bridge - "about ninety men" - stood their ground and then (without orders) fired. Major Buttrick of Concord screamed "Fire! Fire!" and the Patriots fired back. At the Patriots' volley, the Regulars fled. Four British officers and three men had been killed; two Patriots had been killed.

Surprised by their victory, and unsure what to do next, the militia stayed around the North Bridge. Meanwhile, Smith in the center of Concord waited unsure. Finally, at noon, Smith ended the standoff by marching back toward Boston. More militia would be waiting for him en route.

Tho ground is covered with their dead

No reinforcements near

For every tree contains a gun

Behind a fence a foe

The Wiley’s fox’s face is run

The Tyrant’s got to go-- Ebenezer Stiles, "Story of the Battle of Concord and Lexington", 1795

The road Smith and the Regulars took back to Boston is called the "Battle Road."

It was one long battle - a series of shots and ambushes by Massachusetts militia waiting along the one road they knew the Regulars would be heading down. In the morning, the militia had still been gathering under orders to not fire the first shot. Now, they were ready, they knew the war had started and their neighbors had been killed, and they were hot for blood.

We don't know how many were killed where, but even aside from the numbers, the tired Regulars were unsure they were ever going to get back to Boston alive. Smith was shrewd; he sent out flankers through the fields alongside the road who surprised and killed some of the Patriots in turn. But there were more Patriots, and they knew the area because they lived there.

Smith himself was wounded at Lexington (where Parker and his men had their revenge), and the demoralized column was about to surrender when another column under Lord Percy - having marched from Boston by land starting at 9 AM - came to rescue them.

The ordinary people of Massachusetts - farmers and townsmen, who'd been training part-time through the last winter - had defeated the elite of the British Army. They hadn't just started a war; they'd won the first battle. This moment would go down in American tradition forever. Ordinary civilians had come from their homes to fight for their liberties, and won.

(Soon, the Continental Congress would realize that wasn't everything; they did need a trained full-time army of their own. But the militia remained a very significant thing.)

By the next day, news had spread throughout most of Massachusetts and parts of Rhode Island and New Hampshire, and Patriot militia companies - of normal farmers and townsmen, just like the militia who'd already fought at Lexington and Concord - were rushing towards Boston. Swiftly, the news would race further toward the Middle and Southern Colonies as well.

These militia would swiftly turn the self-made siege of Boston into an actual siege. The Battle of Lexington and Concord would not be forgotten; it turned the American Revolution into an actual war, which led to actual acknowledged independence from Britain.

As Samuel Adams was fleeing for safety from Lexington, he commented to Hancock, "O! What a glorious morning is this. I mean, this day is a glorious day for America." It wasn't glorious at the moment - Adams' correction was well-put, given the farmers dying at that very moment - but in a larger sense he was truly seeing the significance of this day.

John Adams - who was home in the town of Quincy during the battle, preparing to leave for the Second Continental Congress - would later say that the true Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people long before the war. He was close to correct: it wasn't just their changed hearts, but everything they had done before the war: asserting their rights and forming new governments for themselves - and starting to form a new nation, though most of them didn't realize it till later.

By the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the true Revolution had already happened. What followed was the Revolutionary War: a war to prove whether (to borrow Lincoln's phrase from a later war) "that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure."

And it did endure.