This continues my series marking the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the American Revolution. Previously was the First Continental Congress, on 5 September 1774; next is the Portsmouth Powder Alarm and Battle, on 14 December 1774.

Two hundred and fifty years ago tomorrow - on 6 October 1774 - the Massachusetts Provincial Congress convened in Salem. Though they carefully didn't call themselves a government yet, they were effectively a new government for Massachusetts, independent of British authority or the British colonial governor, General Thomas Gage.

Before the war had begun, Massachusetts had not just thrown off the British government but - with very little violence and complete order - established its own government.

After the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, the British King and Parliament had punished all the American colonies, but especially Massachusetts. Under the "Massachusetts Government Act", the colonial charter was suspended, General Gage was appointed colonial governor, town meetings were forbidden without Gage's consent, and he was empowered to appoint his own executive council and local court officials who could then appoint their own juries. At the same time, under the "Boston Port Act", the port of Boston would be closed until and unless Boston paid for the tea spoiled in the Tea Party.

When General Gage arrived in Boston on 13 May 1774, carrying news of the Massachusetts Government Act, almost everyone in Massachusetts was shocked and horrified. The first reaction of the colonial legislature (the "General Court", as is still the name of the State of Massachusetts legislature today) was to object that this violated their rights of self-government. Their second reaction was to urge the other American colonies to join in an intercolonial Congress. Gage immediately responded by dissolving the colonial legislature.

That invitation would be accepted by eleven other colonies, in what was soon called the First Continental Congress. That Congress would meet on 5 September 1774, in Philadelphia, per the Massachusetts General Court's invitation. It would reaffirm that the other colonies (many of whom had already been sending charity to Boston) were behind Massachusetts' resistance.

In the meantime, resistance in Massachusetts would quickly grow to the point where General Gage was afraid to do anything about it.

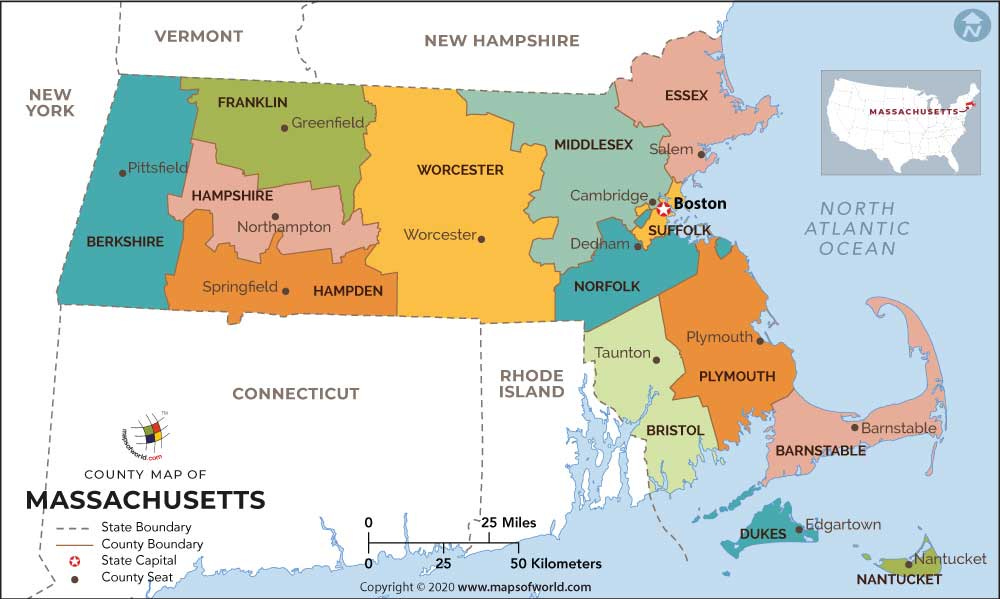

The first move came from Berkshire County, at the far western edge of Massachusetts. On July 6th, delegates from every town in the county met at a county convention to organize against the Massachusetts Government Act. As Gage realized, Berkshire County was simply too remote for him to do anything to stop it. If he sent a few troops west, they could easily be ambushed and defeated; if he sent more, he would be dangerously understrength in Boston.

But even when closer towns decided to ignore the Act and have town meetings or county conventions anyway, Gage found there was nothing he could do. In Salem, when Gage sent two companies of soldiers to dissolve the town meeting, they simply adjourned quickly before the soldiers could arrive; when he tried to arrest the people who'd called it, the county judge released them without bail. One or another of these scenes was repeated regularly, until - as Boston merchant John Andrews wrote - "a day in the week does not pass without one or more [towns] having meetings, in direct contempt of the Act."

The town meetings insisted on action. The Sons of Liberty in Boston - who had organized the Tea Party the previous year - quickly found themselves outdone by the rest of Massachusetts.

General Gage still sat unchallenged in Boston, but all his appointed Councilors and judges were helpless to do anything. Quickly, crowds of men from the town meetings coerced the Councilors to resign their seats or else flee to Boston where the British army could protect them. Similar crowds tarred and feathered, or otherwise intimidated, local Loyalists whenever they let their sentiments be known, until many of them fled to Boston and the rest remained silent.

This might look like mob action, but the vast majority of Massachusetts considered it democratic action. Gage's government was enemies of the rightful government of Massachusetts. Anyone who supported it, therefore, was also an enemy. An overwhelming majority of the people of each town agreed to this; therefore, each town would defend itself. But it would do so in a sober and organized fashion - none of the Councilors were killed; no action was taken without consultation.

Then, when the courts were to open, the counties' militia surrounded the courthouse and prevented the newly appointed judges from holding court. The first time this happened was in Worcester on September 6th, but it was repeated whenever another court was to open outside Boston.

Throughout all of this, General Gage feared to leave Boston. He knew that, with the entire province of Massachusetts against him, he couldn't win a war. There was an insurrection, but not a war... yet.

All of Massachusetts outside Boston had now effectively thrown off British authority. The province was staring down Gage's army on its rare trips outside Boston. Without a battle, a revolution had already taken place.

But, there was no leadership visible. I haven't named people like John Adams, Samuel Adams, or Joseph Warren because they weren't taking the lead here. Everything was done by individual towns' meetings, which meant by every property-owning man in the town debating, or by delegates from the meeting to advisory county conventions. This was very cumbersome, especially when trying to negotiate a councilor into resigning. Everyone could see something more was needed.

It was the Worcester Committee of Correspondence that sent representatives to the Boston Committee to decide what must be done. There would be a "Provincial Congress" to make decisions that the towns would "resolutely execute." In effect, Massachusetts would have a new independent government.

But, the Patriots wanted a legal excuse to set up their independent government.

So far, the Patriots had - in their minds - been staying strictly legal. They'd been scrupulously adhering to their colonial charter, which they argued was still valid as Parliament could not revoke it. The "mandamus councilors" were not really members of the Council; judges appointed by the Governor were not really judges so the things they'd been closing were not really court sessions. Everything the Patriots had done was under the authority of town meetings. But to move beyond that and prepare for the war everyone could see was looming, they'd need something beyond town meetings and unofficial county conventions.

Gage gave them the excuse: On 1 September, he summoned the General Court and Council to meet in Salem on 5 October, but then (on 28 September) changed his mind and canceled it. He'd decided it wouldn't be profitable thanks to the united resistance, but actually, canceling it played right into the Patriots' hands.

On 5 October 1774, ninety delegates elected to the General Court met in Salem anyway. The next day - 6 October - after giving the governor and council a due chance to show up, they organized themselves as a convention. The day after that, they officially resolved that the governor's actions were "unconstitutional, unjust, and disrespectful to the province"; that he could not validly cancel a summons to the General Court; and that they the delegates (and whatever other delegates might be elected) were now a "Provincial Congress" to "consult and determine on such measures as they should judge will tend to promote... the peace, welfare, and prosperity of the province."

They then adjourned to meet again in Concord on 11 October, where over two hundred other delegates would shortly be waiting to meet them. Altogether, 209 of the 260 towns in Massachusetts sent delegates to this Provincial Congress. This was far more than had ever been represented in the General Court, since towns needed to pay their own representatives, and many towns usually didn't think it worth the expense. Now, though, everyone saw that "the dangerous and alarming situation of public affairs in this province" demanded this Congress.

Without any fighting - months before the war began - the people of Massachusetts had created their own independent state government, in the form of the old one. Just like the American Revolution as a whole wasn't trying to throw off the old forms of government, Massachusetts wasn't trying to change things here. The American Revolution wasn't centrally defined by mobs or military force, but by a new government carrying on in the tradition of the old.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress was doing just that. Though they didn't call themselves a government, they acted like one. Reluctant to offend moderates still hoping for reconciliation, they issued "recommendations" rather than "laws". They organized themselves like the General Court but didn't claim the General Court's authority.

But, the Provincial Congress "recommended" everything a government would command. In late October, they appointed a "Receiver-General" and directed all taxes be paid to him. That money would be spent on buying a long list of guns, gunpowder, and artillery (some from abroad; some from English merchants happy to sell). And, that artillery would be in the hands of a reorganized Massachusetts militia - under new field officers, with a new province-wide commissary, drilling to a more exacting standard, and with new detachments of Minutemen ready at a minute's notice for war.

Meanwhile, General Gage - still the royal governor of Massachusetts, and nominally recognized as the governor even by the Provincial Congress - dared not do anything. His superiors in Britain had refused to reinforce him; he had only 1800 ready troops in Boston. If he wanted to suppress the rebellion, he kept protesting to Britain, he would need "an Army near twenty Thousand strong" to essentially conquer New England. As it was, he barely dared stir outside Boston. Any confrontation, he feared, might lead to a battle. And if he lost - which he saw he easily could - that would ruin the British cause. Instead, he kept waiting, in hopes that Britain would finally believe him and send more troops.

This brinkmanship lasted through the winter of 1774-1775, while the Provincial Congress kept sitting as the first independent state government in America. This was a crucial turning point in American history. Without firing a single shot, Massachusetts had successfully dismantled British authority, replacing it with their own independent government under the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. The Provincial Congress commanded the loyalty of nearly the entire population, administering taxes, writing laws, and organizing a militia to prepare for the inevitable conflict.

That conflict would break out in the spring of 1775, when the increasingly-desperate General Gage finally (to his dismay) got new orders from London to arrest the Provincial Congress's leaders. As he'd foreseen, he couldn't do it. Instead, his attempt sparked open war against the Massachusetts minutemen - and soon, against a Continental Army from across America. Then, the Provincial Congress would finally declare Governor Gage had "utterly disqualified himself to serve this colony as governor" and call elections on their own authority for a new General Court.

With each step, Massachusetts had paved the way for a new nation, built on the foundations of self-governance according to law and upholding the rights of the people. The war was still months away when the Provincial Congress assembled, but the revolution had already begun.

I note with amusement that Norfolk is south of Suffolk.