I was recently reading about railroads in the American Civil War. It was fun, and eye-opening in several ways. I'd known the basics of the armies using railroads for supplies, but I hadn't appreciated many of the difficulties, or how they overcame them.

One other thing the books didn't talk about, but stood out as I was reflecting, is how unprecedented a difference railroads actually made here.

At the beginning of the war, most European observers expected the Union to lose because the South was just too large. An army couldn't fight its way far enough into it in a reasonable time, and couldn't occupy it once it’d fought its way there.

Going by any past wars, they probably would've been right. But this war was different.

With the occupation, the observers were ignoring how a large part of the Southern population was slaves who were overjoyed to join the Union as soon as they could. But that's another point I've already talked about elsewhere.

The other thing they were ignoring was how technology had changed.

The armies in the Civil War were no larger than previous armies, and indeed sometimes smaller. At the 1864-65 Siege of Richmond, Grant and Lee's armies were comparable to the Allied and French armies respectively at the Battle of Waterloo - but Waterloo itself was fought with armies that’d been hastily assembled after Napoleon returned; the Battle of the Nations the previous year before his first fall had been much larger.

The difference was that, unlike Napoleon's armies, the armies in the Civil War could keep feeding themselves on the move. They didn’t have to pause to forage food from the local inhabitants, or to wait for the supply train to catch up. In Napoleon's era, armies marched in separate columns to combine for battles, so that no one column would overforage an individual area. He did have a supply train, but it was limited to wagons, so it was intermittent and slow.

Civil War armies, on the other hand, were for the first time1 being supplied by railway. They could stay together. This made operations simpler, and meant that a surprise attack (like at the Battle of Shiloh) couldn't catch a single column unawares.

Of course, this also made things vastly easier for the people nearby. The dull word "forage", basically, means stealing food from the local people, threatening them with starvation, and giving a perfect chance for unscrupulous solders to steal or maraud in other ways too. When old tales lament over soldiers' bad morals, this is why.

For perhaps the first time in history, foraging was illegal in the Civil War. It happened anyway - but on a small scale, a shockingly small scale by historical standards. All this was thanks to railways. When Sherman cut loose from his supply lines and marched through Georgia with the purpose of devastating it, any pre-railroad army would have been very familiar with the sort of devastation that happened.

The idea of a logistics system wasn't new. One big reason the Romans could supply such large armies throughout their Empire was their logistics system. In Roman forts in Britain, archaeologists have found food shipped from across the empire.

But the difference in America was how quickly and freely it was shipped. Before railroads, cheap shipping meant water. Roman armies were bound to the coastlines or rivers, or else forced to forage from the local population. Shipping along roads was possible, but much more expensive because everything that could carry food also ate food. Now - supplies could run anywhere you could run a train, much faster than before.

This held for men, too. Casualties were evacuated, and reinforcements brought up from across the country, in hours or days. Multiple whole divisions were transferred between Eastern and Western fronts in days.

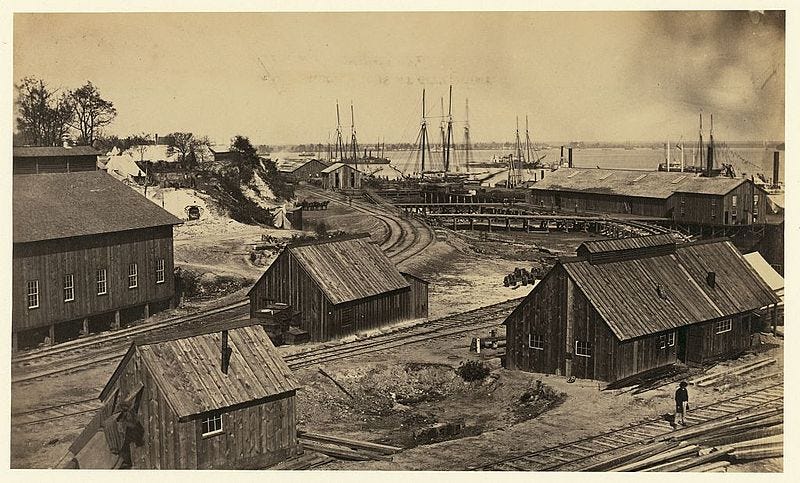

This wasn't a simple matter, even given that railways existed. It took more organization than railroads had ever needed before.

Throughout the North, railroads were seeing far more long-distance traffic than ever before. In part, this was because of the war, but more of it was due to the Mississippi River being closed. Regardless, overall freight traffic increased by roughly 15% on the Erie Railroad and ~20% on the New York Central in the first year of the war versus the last prewar year. The Civil War era was what first molded the railroads into a cohesive net.

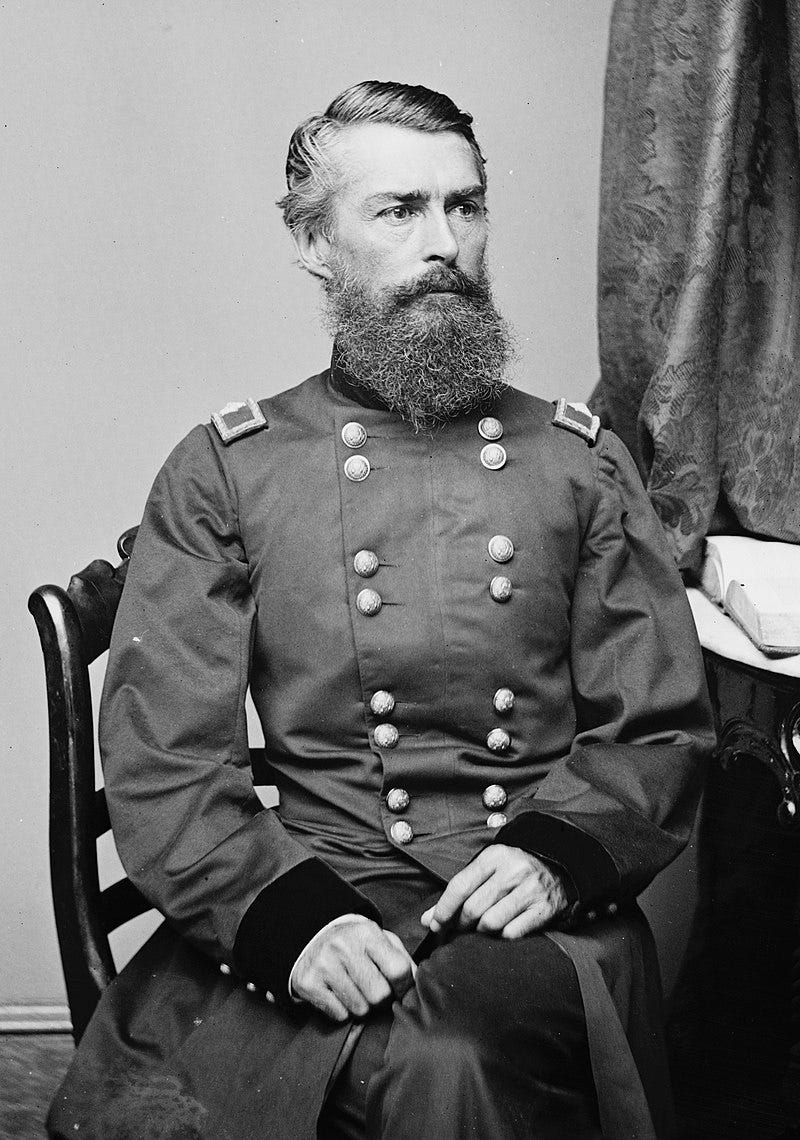

Railroads closer to the battle lines demanded even greater organization. As General Herman Haupt of the US Military Railroads said, "A single track road in good order and properly equipped may supply an army of 200,000 men, when, if these conditions were not complied with, the same road would not support 30,000."

Haupt himself, actually, provided most of the Union's organizational effort. He organized his construction and operations corps under strict discipline, demanding trains run exactly on schedule (a new concept) and be unloaded promptly, regardless of whatever any other officer might say. After he resigned in December 1862, he was called back and almost singlehandedly enabled victory at Gettysburg by supplying the Union army over a brand-new supply line of single-track railroad. By the time he resigned again in September, he had infused the US Military Railroad with enough of his drive that they could continue without him.

The Confederacy didn't even approach the Union's triumph. In large part, that was due to their laughably small industrial base. They could only build urgently-needed new rail lines by ripping up existing lines to reuse their iron, and they didn't build a single new locomotive in their entire existence as a nation.

But even beyond that, their use of what they did have was much worse than the Union's. In late 1863, Lee's army was encamped right on a rail line to Richmond which had been running throughout the war. It was still running. But, mismanagement and bad maintenance meant it couldn’t carry enough supplies. Lee’s army was still starving, almost as badly as a pre-railroad army would have been.

I’ve been talking about the American Civil War here, but quick transportation of food and supplies changed a lot more things than just wars.

Before modern times, famine was a constant threat. Villages organized their farms to stave off the chance of complete crop failure in every possible way. Even so, it remained a possibility - because if one region lost its harvest (whether from drought or blight or war), it would be all but impossible to import enough grain to make it up. The only theoretical possibility would've been by sea, and even sea transport would've required so much grain that hardly anyone would ever have been selling it. Even in the Roman Empire when there was a long-distance market for grain, regional crop failures caused the supply to drop and price to rise so high that most people would be on the edge of starvation if not starving.

Nowadays with modern transportation, no famine has ever been seen in a modern democracy. In 1861 at the start of the American Civil War, Europe had a large crop failure - so they bought grain from the United States. The Mississippi being closed by the war, the grain was largely shipped over railroad to Atlantic ports where it was transferred to steamships. None of this would have been possible even fifty years earlier.

Beyond just preventing famine, this's enabled modern cities to grow larger, with a more varied diet, than ever before. At my local grocery store, I can buy fruits and vegetables from all over the world, and meat from all over the country, regardless of the season.2 All of this is shipped into my city over distances unthinkable in premodern times, without needing to worry about livestock grazing en route or farms taking up valuable land near the city.

Truly, we live in an age of wonders.

Technically, one railroad had been used earlier in the Crimean War, but that was over an extremely short distance (14 miles) to established siege lines.

Fresh fruits and meat, too, thanks to modern refrigeration!

It is worth noting that even today in 2024, the Russian forces in Ukraine are mostly supplied by rail. In places where there is no rail link they have generally been forced back.