This week in history - May 14, 1800 - the United States Congress recessed for the final time in Philadelphia, before its move to the new capital: the newly-built Washington City in the new District of Columbia.

It had been a surprisingly difficult time getting to this point, and Washington City - "Washington, DC" as it's now called for short - would keep creating interesting footnotes in history to the present day.

When the United States declared independence, the Continental Congress was sitting in Philadelphia. Philadelphia was fairly central in the new United States, and also its largest city. (New York would pass it in 1790, and remain the country's largest city through today.) However, Philadelphia would also be threatened by British troops in late 1776, sending Congress fleeing to several nearby cities. After peace, they fled again thanks to an army mutiny which Pennsylvania was unwilling to suppress, and eventually settled in New York City. When the Constitution of 1789 was ratified (the one still in effect today), the new government stayed in New York City.

But, most Congressmen, and most of the state governments, weren't satisfied with that. They all assumed the capital city would naturally grow into a large and important city, the focus of political and economic power. So, they all hoped to get the capital closer to them. Americans today, with many cities larger than Washington DC, and many state capitals in small towns, might scoff at this. But it was true then in most countries, and it's still true today - usually, the capital city is the largest city - and frequently many times the size of the next largest. Americans in the 1790's wanted those benefits for their region.

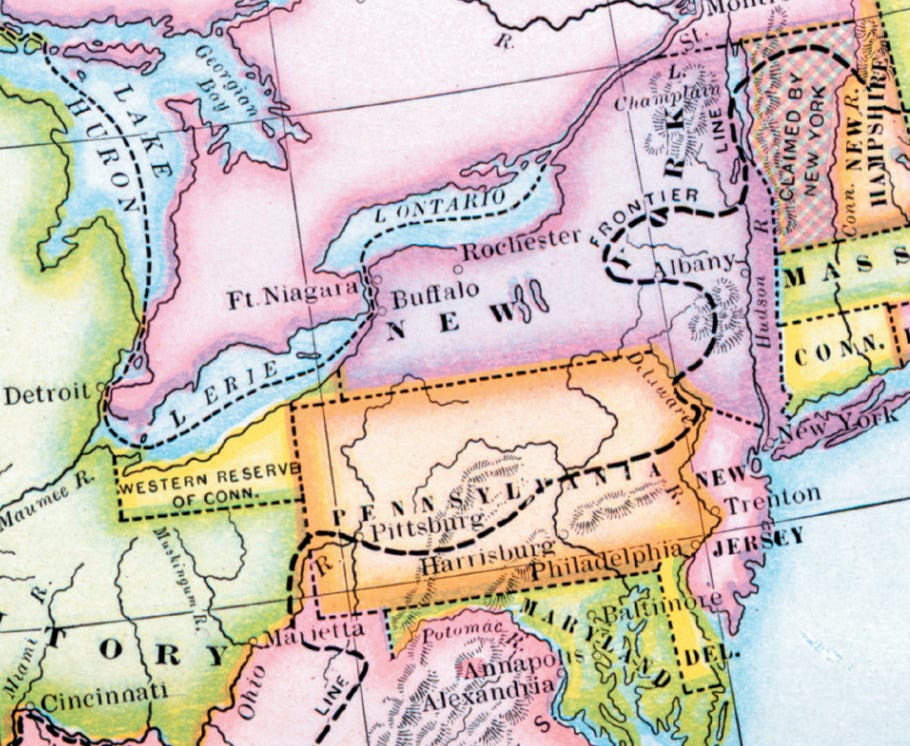

Within the first year of Congress's existence, sixteen possible sites had been proposed for the permanent capital, from the Potomac north to New York City, and Congress was consumed with arguing about them. The intricate fight was "a labyrinth," as Representative James Madison put it, "which it is impossible in a letter to explain." Various hopes of the future were bandied on all sides, most of which would prove futile: Virginians claimed that the Potomac was the best avenue to cross the Appalachians (it isn't, and never was); Pennsylvanians claimed their state would remain the center of the Union since the trans-Appalachian West would never join as states.

Finally, the issue was resolved as a compromise - said to be a compromise with then-Treasury Secretary Hamilton's plan for the Federal government to take up the states' debt.

The Revolutionary War had been expensive.

To fund the war, the Continental Congress had borrowed money from France and the Netherlands, and effectively borrowed from their own soldiers by partly paying them in bonds. Still, the states had also had to borrow: in part from European financial markets as well, and in part from their own people. Treasury Secretary Hamilton insisted that the new federal government would pay back Congress's old debt, and he wanted to assume the states' debt and pay it back as well.

Hamilton had three main arguments. First, the states had borrowed to pay for the Revolution, which was a common cause, so why shouldn't all states share the burden together? Second, Congress - with authority to tax across the country - would be better able to repay the debt than individual states.

But third, and more deeply, Secretary Hamilton reasoned that making creditors depend on the new federal government for payment would encourage them to support the new federal government. This wasn't just major bankers; a number of people - from lawyers with money to invest, to people who'd done business with the states - had such loans. Hamilton correctly saw the new government needed support, and he figured that financial incentives would be useful.

However, Hamilton's opponents - led by Secretary of State Jefferson and Representative James Madison - replied that some states (like Virginia, where they were both from) had already paid off most or all of their debt; why should the federal government tax them to pay off the debt from other states that hadn't? But also, they were starting to look skeptically at the new federal government, and Hamilton's sweeping financial plans (including things like a new national bank) made them even more skeptical. So, when Hamilton argued that assumption would increase support for the federal government, they saw that as a negative.

(The Hamilton musical summarizes the arguments decently well in rap form.)

The fight over debt assumption, like the fight over the capital, continued for months.

Jefferson would claim afterwards that he, Madison, and Hamilton made a deal one night over dinner: Hamilton would get his way on assumption, Jefferson and Madison would get their way by putting the capital on the Potomac, and they would both lean on their friends in Congress to ratify this compromise.

Modern historians believe Jefferson wasn't being honest there - he and Madison had already struck a tentative deal with Pennsylvania to temporarily move the capital to Philadelphia while a permanent home on the Potomac was being constructed. (The Pennsylvanians hoped that the Potomac capital would never actually finish construction. In reality, it would stay in Philadelphia for nine and a half years.1) But, the deal with Hamilton definitely helped assumption, probably was what influenced Hamilton to give the already-paid-off states more favorable terms when assuming debt, and it probably also helped the Potomac location stay approved.

But we don't know for sure; we weren't in the room where it happened.

To really ensure that it stayed approved, Jefferson and Madison used a trick: they made sure the Potomac location never again came before Congress. Congress would vote on one Residence Act of 1790, listing a temporary move to Philadelphia and a permanent move to the Potomac no later than December 1800; the Potomac location would be "at some place between the mouths of the Eastern Branch and Connogochegue"2; all details would be settled by President Washington without further reference to Congress.

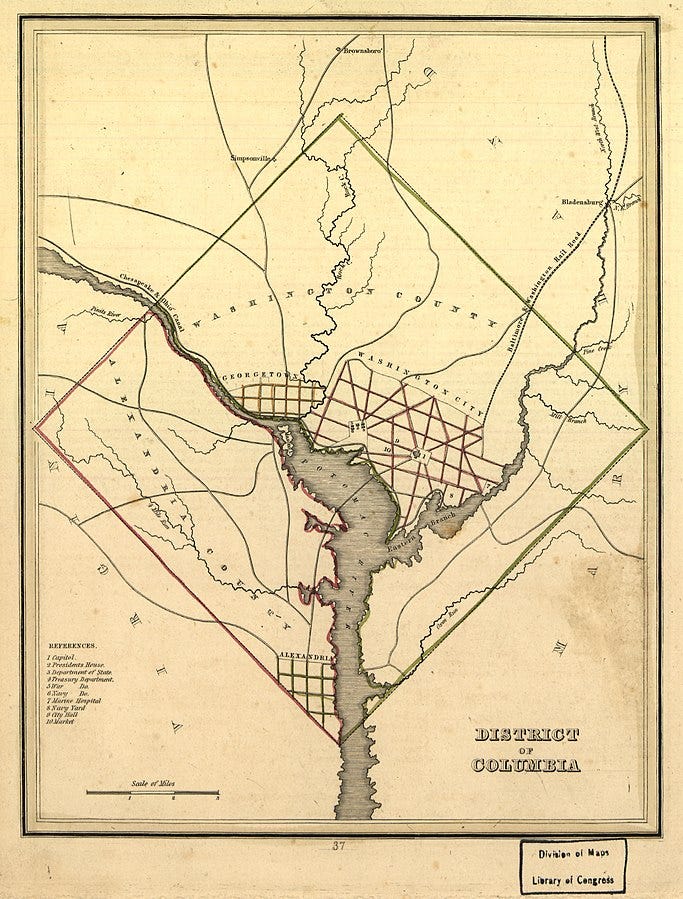

President Washington then promptly settled the location as far East as Congress had let him, adjacent to Mount Vernon and in fact including a substantial amount of land he owned. Of course, this disappointed boosters of the Potomac as a route to the west, who had hoped the capital would be further west. Washington never explained why, and Jefferson described him as "unusually reticent" about the choice.

Outside the two towns of Alexandria and Georgetown, the new federal District of Columbia was part farmland and part swamp - but people promptly started building a new capital city there.

There was one afternote to the federal district, which no one seemed to consider until afterwards. The Constitution declared the capital city would be a federal district governed solely by Congress, so that Congress would have authority to protect the new capital (against, say, a riot or another army mutiny). Accordingly, Washington City isn't in any state; it's in the "District of Columbia." But what no one seemed to consider was that, as a federal district governed by Congress, its residents wouldn't have any self-government. Not only does Congress have authority over the District of Columbia; the District doesn't have any representatives in the federal government because Congress only includes representatives from the states.3

Laconically, all the Constitution said was that Congress should have power "To exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever" over the district. Coincidentally, "in all cases whatsoever" were the very words of the Declaratory Act, by which Britain declared power over America in 1766. As far as I know, no one remarked on this wording at the time - but the citizens of the District remarked on the substance in a petition to Congress in January 1801, protesting they "shall be completely disfranchised... We shall be reduced to that deprecated condition of which we pathetically complained in our charges against Great Britain, of being taxed without representation."

(As it developed, those fears would be relevant exactly once, in 1861, when Virginia had seceded and Maryland was contemplating secession and unwilling to defend the federal government. Washington City had also been invaded by the British in 1814, but then state officials were very willing to assist in the defense.)

However, Congress didn't listen to the residents' petition, and empowered the President to appoint almost the entire District government4. This would continue until the new Organic Act of 1871 would merge the boundaries of Washington City with the District of Columbia and establish an elected District Assembly - except that would be repealed in 1874 on grounds of fiscal mismanagement5. Permanent representative government would only come with the Home Rule Act of 1973.

Today, it might seem that both Hamilton and Jefferson got what they wished out of this bargain. As Hamilton wished, United States federal government bonds form the foundation of the financial system, the federal government has never reneged on its debt, and creditors are extremely interested in its fortunes. Also, as Jefferson wished, the capital has remained on the Potomac to the great economic benefit of Maryland and northern Virginia: a huge part of the local economy is centered around the federal government.

However, the benefits to the regional economy didn't arise until much later. As late as 1860, only 75,000 people lived in the District of Columbia. Hardly any federal employees existed to reside there - most federal jobs were in the post office and customs service, who would of course live away from the capital. It was the Civil War that grew DC, and the expansion of the federal government with the New Deal and World War II catapulted it into a major employer beyond the District itself. So, when Jefferson protested later in his life that Hamilton had gotten the better of the deal, he was quite correct at the time.

But in a deeper sense, I think Hamilton got the better of the deal even today. Jefferson, and the Republican Party he founded6, favored farmers and rural life. Large cities he described as "pestilential to the morals, the health, and the liberties of man." Jefferson would look at the modern DC urban area with horror - and all the more horror, I'm sure, to see it in his home state of Virginia.

I think this's a microcosm of how Hamilton's influence is more visible in the modern federal government as a whole. None of the Founding Fathers came close to anticipating the government's modern size and power, but Hamilton came closer than most of them. He was the one who pushed forward a strong federal bank and unsuccessfully pressed for federal veto over state laws, as well as supporting more widely-favored proposals like an independent federal judiciary and customs service. Out of all the Founding Fathers, I think it's Hamilton who would come closest to recognizing the modern District of Columbia.

This week, the anniversary of the government's move to the District of Columbia, I'm marveling at how much things have changed since then - in Washington City and in the federal government. And also, I'm shaking my head at how many things in politics have unexpectedly stayed the same.

Also, the details that went into the siting of the capital in Washington DC are just one example of how many different paths history could have gone down, there and in general. The Founding Fathers chose this course, only guessing at what it would mean. But there were so many other possibilities, and we still can only guess what impact any of those other choices might have had.

The main street in Washington City between the Capitol and the White House is named "Pennsylvania Avenue"; historians don't know for sure, but it's guessed that name might have been given as a consolation prize.

The "Eastern Branch" is the Anacostia River that flows through the modern District of Columbia; the Connogochegue flows into the Potomac at modern Williamsport, MD.

Today, the District of Columbia (like other territories) has one non-voting delegate in the House of Representatives. But, that delegate still isn't technically a member and accordingly can't vote. They also have three electoral votes in electing the President, but that's thanks to a Constitutional amendment specifically giving it to them.

The exception was the cities of Georgetown and Alexandria, which preexisted the District of Columbia and continued to exist under their old charters. The President would appoint the Mayor of Washington City, and Boards of Commissioners for Washington County (the parts of the District on the Maryland bank of the Potomac, outside Washington and Georgetown Cities; now part of Washington DC) and for Alexandria County (the parts of the District on the Virginia bank, outside Alexandria City; now Arlington County VA and parts of Alexandria VA.)

Alexandria City and County would return to Virginia in 1847, after their repeated petition.

Interestingly, the mismanagement was by the appointed governor, not the elected assembly.

There's no direct relation to the modern Republican Party, which started in 1854 as an antislavery movement. Some historians call Jefferson's party the "Democratic-Republican Party," a name that some of them occasionally used at the time; but the normal contemporary name was "Republican Party."

"usually, the capital city is the largest city"

This is because of the corruption of politics. Politicians leech the wealth of a nation and bring it to the capital city like vampires. We should instead look to build countries where the capital city is an insignificant backwater.