I once saw someone ask online what Shakespeare might have written about the French Revolution, if we ignore how he died long before it and pretend he could've written about it. Recently, I was musing over it again.

235 years ago tomorrow - on 14 July 1789 - French revolutionaries stormed the royal prison called the Bastille, to release prisoners oppressed by the aristocracy. The French Revolution had already started, but this was taken to symbolize its heady early days. It's still remembered today as France's national holiday, "Bastille Day."

But, the revolution that had begun with such great promise turned into a tragedy. Just like Caesar's assassination is only the start of more war and violence in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, and Duncan's murder yields more war and murder in Macbeth, storming the Bastille and abolishing aristocratic privileges was only the start.

After waves of sweeping reforms and changes frequently reversing each other, executing the King and his whole family, and mass executions of people thought to oppose whoever was on top at the moment - and war against most of the crowned heads of Europe who were horrified at what was happening - the Revolution fell to one of its own generals, Napoleon Bonaparte, naming himself first ruler and then Emperor. Then, after Napoleon lost the war and the armies of Europe paraded through Paris, the old king's brother was restored to the throne.

There could be many tragedies found in the Revolution, and I'd like to tease out some.

The core of a Shakespearean tragedy (as I dug into in another post) is that the protagonist ("hero") is put in just the wrong plot, which plays on a failing of his - his tragic flaw - to bring him down to disaster. His choices create his tragedy, but he starts out a noble person and only makes those choices because of just the wrong circumstances.

There're multiple tragic heroes here.

Let's start with King Louis. Shakespeare, being a staunch monarchist who wrote most of his historical plays about kings, would've liked to start with him. King Louis didn't seem to like the business of being king, and he certainly didn't see the need for reform. My own impression of him is that he did want to help France - but if so, he certainly wasn't good at it. He was in a bad situation at the start of the Revolution, because his government was legitimately bankrupt, and the ideals of the (very recent) American Revolution were very popular in France. Then, he didn't want to give up power and become a constitutional monarch, but he felt forced to give in - and he gave in with such visible reluctance that it emboldened the revolutionaries to demand more. That was his real tragic flaw: he ended up being lukewarm and sitting on the fence.

Perhaps Shakespeare could pick on that. The revolutionaries' initial demands for a constitutional monarchy did echo the British monarchy; Shakespeare could make much of comparisons like that. But even so, the interplay of power between Crown and Parliament was too politically sensitive in Shakespeare's day for him to mention in any of his historical plays.

So, I think instead he would've played up how many of the revolutionaries were villains, and painted King Louis's tragic flaw as his cowardice and unwillingness to face them. This might be similar to Hamlet's self-doubting excess of caution, or perhaps King Lear's fall to flattery. All of this was quite true of King Louis.

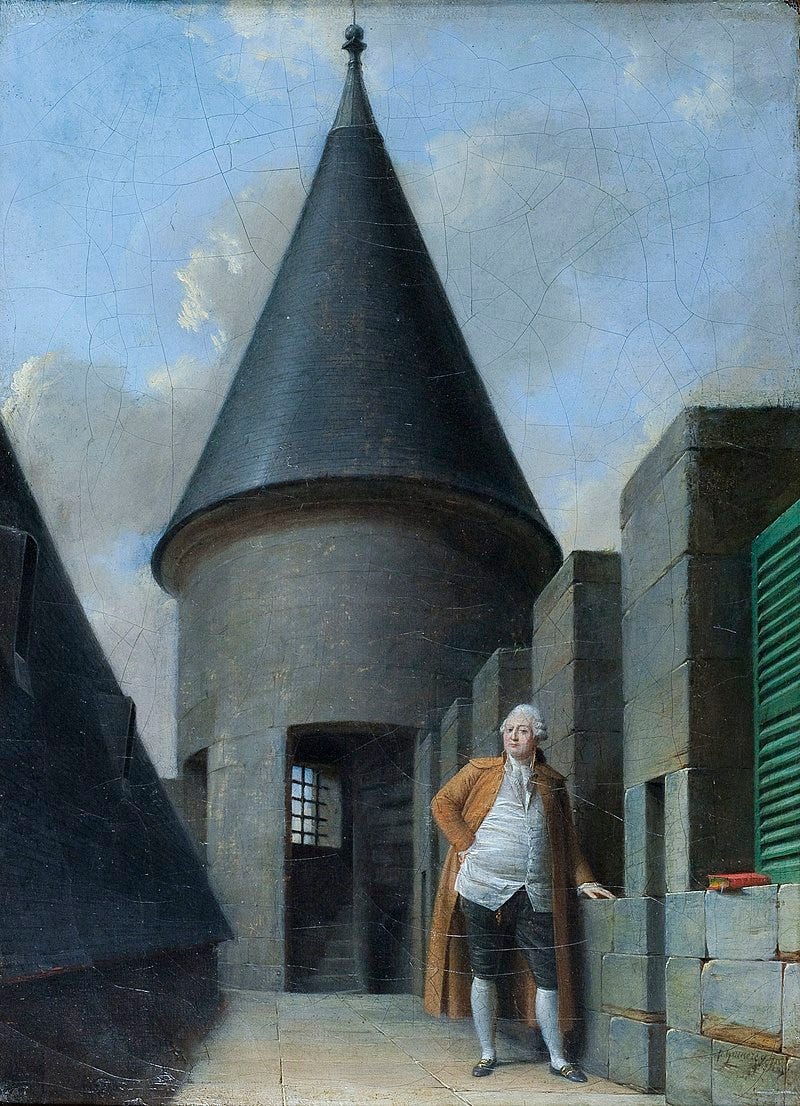

As the Estates-General was growing more and more radical, King Louis tried to flee to the Austrian army on the border of France. This, to Shakespeare, would've been the turning point. King Louis's escape failed; he was brought back in name as a constitutional monarch but in practice as a prisoner. A year and a half later - after more riots - he was officially arrested, tried, and (on 15 January 1793) sentenced to death.

King Louis's last words were, "I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France." Shakespeare would have dressed up this eloquence with even more eloquent words, and had him beg forgiveness for his tragic flaws as well.

The second tragedy interwoven with this was the Marquis de Lafayette, called the "Hero of Two Worlds." He had fought in the American Revolution and gained George Washington's favor for his truly believing in American ideals of liberty. King Charles - who eventually took the throne after the bloody cycle of the Revolution was over - once said of him, "Since the Revolution there were only two men in France who never changed, M. de La Fayette and myself."

That consistency was his virtue and his tragic flaw. He was brought down mostly by his virtues, in a way simpler than any of Shakespeare's actual tragic heroes. The closest analogy might be Coriolanus, but even that's a stretch since Lafayette refused to compromise himself to fight his friends.

Lafayette spoke in the Estates-General for a constitution; he commanded the National Guard in name of King and National Assembly while he still could. But that left him as a moderate amid the growing radicalism of the revolution and the tragic reluctance of the King. So, the ground around him got hollowed out until - by late 1791 - he had lost the trust of both sides.

Then - in December 1791 - Austria invaded France, to rescue King Louis from the National Assembly still officially reigning in his name. Lafayette, with more friendship to the Revolution than most officers, was appointed to command one of France's armies. But, he distrusted his soldiers and tried to command in the old aristocratic way. In turn, the soldiers distrusted him and denounced him as disloyal. This was partly correct; he was indeed denouncing the radicals who'd taken control of the National Assembly. In August 1792, shortly after the King's escape attempt, a warrant was put out for Lafayette's arrest.

He deserted to the Austrians, and would stay their prisoner for the next five years until Napoleon negotiated his release.

The last tragic hero of the Revolution was Napoleon. After several cycles of unstable governments, General Napoleon Bonaparte forced the legislature to declare him "First Consul," and later crowned himself Emperor of France. And then, at the head of French armies, he conquered most of Europe.

On the one hand, as many said at the time, he betrayed the Revolution: he declared himself Emperor; he turned the rest of the government into rubber stamps; he harshly taxed France and censored the press and suppressed any opposition. But on the other hand, he ended feudal privileges wherever his armies went. He welcomed talent wherever it could be found, without regards to birth. And, he instituted a new legal code based on reason to replace the old code based on tradition and feudalism.

Napoleon's pride and talent had served him well so far; he was ruler of most of Europe. But, England stood unconquerable, defended by the sea and its navy. There's great drama in that stand; Shakespeare would play it up in full measure. Then, irked by unconquerable England, Napoleon overstepped into hubris: he invaded Russia. The Russian army kept retreating without giving battle, and Napoleon kept marching until most of his army had died in the Russian winter.

That was his turning point. He fled home and raised a new army, but that failure had caused his allies to desert him, and final defeat quickly followed with a Russian army marching into Paris and Wellington leading an English army to defeat Napoleon in one last battle on the field of Waterloo.

Shakespeare might paint Napoleon as a simple villain, in the way he painted Richard III or Joan of Arc, whose stage characters have almost nothing in common with the actual historical persons. British propaganda did paint Napoleon like that, and aligning with it would score our hypothetical Shakespeare some easy patriotic points.

But if he wanted to make a richer character, I could see Napoleon as something like a more eager Macbeth. He was lured into seizing power and a crown, only to find that to keep it he needs to keep fighting more and more. Macbeth did it for safety, but Napoleon did it to try to satisfy his pride. Both of them ended up at disaster.

There are so many more stories that could be told about the French Revolution. Some of them have been told - for three very different novels with mostly-fictional characters there, I can recommend Victor Hugo's Ninety-Three or Charles Dickens' Tale of Two Cities or Baroness Orczy's The Scarlet Pimpernel. Or from a very different angle, I recommend H. G. Parry's recent historical-fantasy novel A Declaration of the Rights of Magicians.

Yet there's more that could be told, especially more that (as I said last week) highlights the actual events. I could see even the villains like Robespierre and Marat being tragic heroes. Shakespeare would be afraid to try to excite sympathy for people who'd done such horrors, especially militant atheists who'd executed their king and persecuted Christianity. And he would be right, they did fall into horrible evils in their Reign of Terror. But - horribly - I think they sincerely believed it would be good for France in the end. Even if they'd been correct there, it wouldn't have justified them. But a tragic irony is they were wrong; they led to Napoleon and then a royal restoration.

Shakespeare was far from the last historical playwright, but in recent centuries, the genre has fallen from his heights of poetry and his heights of characterization. I wish a playwright of his caliber were around to tell the more recent tales.