There're two approaches to what might be called historical fantasy. The more common one is to rewrite the society to enlarge on the fantasy elements. In the extreme, this's something like Tolkien's Middle-Earth, what I call "fantasy medieval": it's medieval in technology and in the general organization of society, but it only has vague counterparts to any specific medieval countries or events. Tolkien, a professor of early medieval literature, does that much better than many of his modern imitators such as the Dungeons and Dragons settings. But still, this's very different from the actual Middle Ages.

The other approach is to keep the historical society and fit in the fantasy around that.

I recently reread two very good books which took that second approach. They put fantasy elements, or what could just as well be fantasy elements, in a realistic medieval society. (A medieval European society, in these cases, but I think it could be done similarly elsewhere.) And, they both take a good perspective on how to integrate the two: they place the fantasy elements - whether werewolves or elves - at the margins of medieval society.

They're both good books, and I think they point to a lot that can be said about this approach of medieval historical fantasy.

When I started reading Gillian Bradshaw's The Wolf Hunt knowing absolutely nothing about it except that my sister had enjoyed it, I thought it was simply historical fiction. I was ready to praise how firmly all the characters were convinced that werewolves existed, and how seriously the narrative was taking that. And then it struck me: perhaps, in the book, werewolves did exist.

It turns out they did, this book is a retelling and expansion of a medieval folktale about a friendly werewolf, and it's a very fun story.

And then I realized that a book I'd read a while back, The Perilous Gard by Elizabeth Marie Pope, does something very similar. There isn't any actual magic there (and our down-to-earth protagonist doesn't ever consider it), but there's a group of hidden people who act like Fey or Elves and are popularly regarded as that by the local village, so the book is best seen as being in this same historical-fantasy genre.

I've read other books that could be counted here, such as Clare B. Dunkle's chilling but shining By These Ten Bones (a werewolf novel in medieval Scotland) and Eloise Jarvis McGraw's charming The Moorchild (the tale of a changeling in an unspecified medieval village). It's a surprisingly popular genre.

But the popularity makes sense, because it works.

What makes it so possible to integrate medieval Europe and fantasy - whether with fantasy-medieval or actual historical medieval - is that most people in the Middle Ages really did believe in magic. They believed in elves, dragons, dog-headed men, witches, curses, and so much more. They'd never interacted with them in detail, but they were sure they existed, whether under the next hill (like the fairies) or halfway across the world (like the dog-headed men).

It wasn't just the peasants who believed this either; as C. S. Lewis explains in detail in his nonfiction The Discarded Image (written for his day job as a professor), all the respected books taught people that unicorns and dog-headed men and all sorts of other creatures existed. Distant sightings of what they called dragons even made it into sober chronicles.

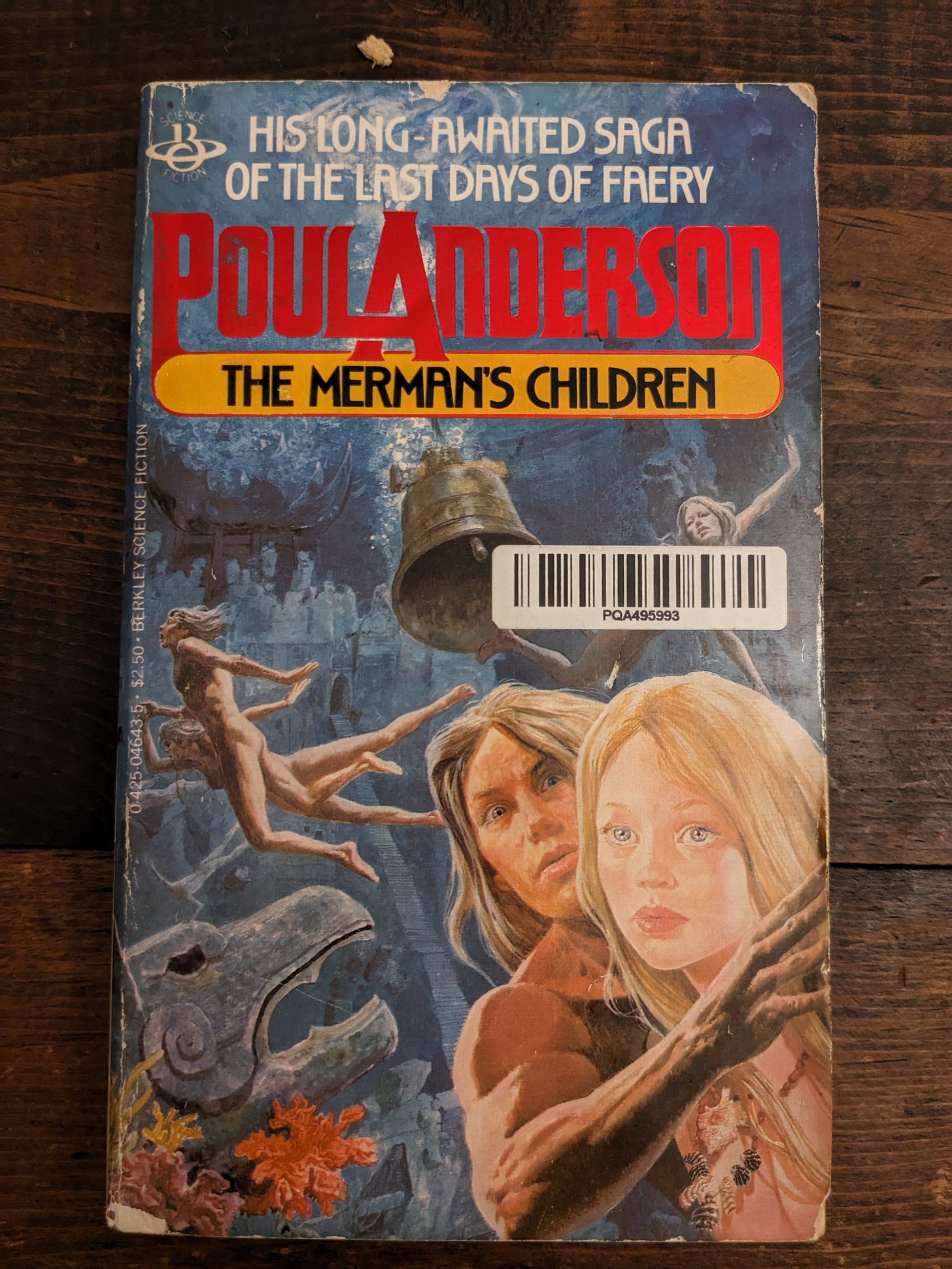

Poul Anderson says in his preface to The Merman's Children that his book isn't set in the real medieval Europe, but the one that medieval peasants thought they lived in. So the setting for his book isn't quite the same as actual historical Europe; in his setting, magical creatures (such as merpeople) are an established fact which virtually everyone - even kings and bishops - can see. But his description points out how well fantasy fits in with medieval Europe and similar premodern settings.

One could say that urban fantasy integrates modern society and fantasy elements. But, the vast majority of modern society doesn't believe in magic. So, urban fantasy set in what's supposed to be the actual modern world has to postulate some "masquerade" to conceal magic from most people in the world. With modern technology and communications, any breach of the "Masquerade" - any magic provably visible to the world in general - will quickly bring the whole thing down. Good urban fantasy needs to explain why and how the Masquerade is kept. Rowling, in her Harry Potter series, had to postulate teams of wizards with memory-erasing magic enforcing the Masquerade. What's more, she set it in the 90's, before the modern Internet. Even that was a stretch, and it'd be more of a stretch today. Naomi Novik, in her more recent Scholomance series, had to make it inherent in the magic - nothing else would work.

(Some other urban fantasy is set in worlds similar to the modern day but where everyone knows about magic. This's similar to the quasi-medieval setting of Anderson's Merman's Children. But, that's different from actually setting a story in the modern world, just like Anderson did not set his story in actual medieval Europe.)

But when you set your book in the Middle Ages, you don't need any of that. Everyone believes in magic already; communications are slow and unreliable. In The Perilous Gard, the entire village around the "Elves" know about them - but that still doesn't break the "Masquerade". When a few people outside the village hear of it, some shrug at it, others scoff at it as a local superstition, and nothing comes of it.

One thing this medieval setting does is - like urban fantasy - draw a clear line between the magic world and the ordinary world. We can see that line in both The Perilous Gard and Wolf Hunt. Our characters start in the normal world, get taken into the hidden world (not literally hidden, but hidden through obscurity) where magic is happening, and then return to the normal world at the end.

The line isn't absolute. In both books, magical elements - whether the Elf-queen or a werewolf - quietly intrude on the normal world. But our protagonists implicitly recognize that as an intrusion, something that should be rectified. Medieval people believed that magic existed, but they knew it wasn't something that happens visibly every day to people around them. To these protagonists, it's an intrusion into their normal lives which are normally just as unmagical as the real Middle Ages.

And it is rectified. Both our protagonists return to the normal world at the end. It's not without regret; both books show beauty in the magical world. The werewolf in Wolf Hunt is happy to romp as a wolf because he loves the beauty of the forest (and describes it in beautiful prose). Even Kate in The Perilous Gard, who's been enslaved by the Elves and then fought them in turn, realizes at the end that there is a sense where she'll miss them. But the magical world isn't a good place for them to live.

Of course, an author could write something like this without including an actual historical setting. But I think the historical setting strengthens it. Reality has depth. Tolkien needs to spend a while expositing the ordinary unmagical nature of the Shire, but setting your book instead in the real world will give all that depth and more, because readers will have the actual real world in their minds as an implicit backdrop to strengthen the contrast.

This setting does close off some possibilities. For example, the werewolf in Bradshaw's Wolf Hunt consults his priest about whether it's a sin to turn into a wolf. The priest has to answer the question on his own. Bradshaw justifies that very well: this priest doesn't trust the bishop or anyone else to give a good answer. But the other reason in the background is that anything else would be too great a departure from the actual Middle Ages where bishops did not receive sober letters from priests who'd personally seen a werewolf.

But, in my mind, the actual Middle Ages add something more to the story.

Perhaps a lot of this is personal to me, because I love history. I read historical fantasy, and other historical fiction, like it's a new work set in one of my best-known and favorite shared-universe settings - because it is. It's a beautiful thing to me.

But even for other people who don't love history so much, I think this historical-fantasy setting can be good. It's got significant things to add to its stories. When Marie from Wolf Hunt, while walking through a medieval forest, first sees a werewolf - or when Kate from Perilous Gard hears how everyone knows the elves are right under that hill and then starts thinking - I think those moments wouldn't be the same without the actual historical setting.

I think you misread, or possibly misremembered, The Perilous Guard. There is magic. It’s not very powerful, and tends to consist of things like illusions or talking people to sleep, but it exists and is very real - as the protagonist observes. Note the scene where her cross breaks. And yes, it’s relevant that it’s a cross.

Although, what is with you and good taste in literature?! That’s another little old one-shot paperback that was surprisingly good that nobody’s read!

(Those ones are always the hardest to find - you can usually notice an author is good and seek more out, but that doesn’t work if the author only ever wrote one or two books. Though in this case she wrote two; I thought the second was weaker, but still solidly worth reading.)

Oh, did you catch the second folk song? It’s built around two.

For a vaguely similar thing which is not European, have you read Bridge of Birds?

(I thought Moorchild was solid, but definitely a kids’ book, with less added when I read it as an adult than many other books. I have not read, or heard of, By These Ten Bones, but seeing the context in which it’s named I suddenly want to.)

Also re Masquerade, have you read War for the Oaks? I get the sense it’s a bit of a genre founder for that sort of urban fantasy, and she has a solid and yet not prosaic explanation for why the masquerade works, which would be a spoiler to explain if you haven’t. But from what you’re describing in this essay, you might like it.

Historical fantasy as a genre has always puzzled me. In some sense all fantasy is historical, for the reasons you explain. It all comes from the past. It is fairytales and folklore and Norse myth, and Arthurian legend all mushed together and projected forward or backward or into strange worlds. It baffles me that people don't seem to recognize the Arthurian elements in Lord of the Rings: Aragorn is Arthur, Gandalf is Merlin, the fellowship of the ring are the knights of the round table, and the ring is the anti-grail. I never know whether to classify my own novel, Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight, as historical fantasy, or dark fantasy, as some seem to categorize it, or literary fairytale as I like to call it, or pseudo-Arthuriana, as another reviewer astutely dubbed it. It is all these things. And that seems to be true of most things in the genre. A little bit more of this. A little bit more of that. But basically all the same stew. It is, in the end, the spirit-haunted world, and it all flows back to what seems to us now, as it seemed to them then, a spirit-haunted time.