The Norman Conquest, Part One

William the Conqueror and the last successful foreign invasion of England

This week in 1066, 14 October1, was the Norman Conquest of England. Duke William of Normandy killed Harold Godwinson king of England in the Battle of Hastings, the English fled, and William marched in triumph to London where he had himself crowned king.

Ever since then, he’s been styled “William the Conqueror.”

In a real sense, the Norman Conquest was the last successful foreign invasion of England. One could argue the point about some later invasions - such as the Battle of Bosworth Field or the Glorious Revolution - but the Glorious Revolution was invited by the English political class, and Bosworth Field and most other later invasions were mounted by someone from the English royal house. William of Normandy had no blood claim to the throne and only the most tenuous other claim, virtually no English support, and seized the throne and governed as a foreigner. England was conquered and subjugated in a real way it has not been since.

“You’ve come, have you?”, he said. “You’ve come, you source of tears to many mothers. It is long since I saw you; but as I see you now you are much more terrible, for I see you brandishing the downfall of my country.”

-- Aethelmaer the monk, on seeing Halley’s Comet in early 1066, deeming it an ill omen

At the beginning of 1066, King Edward of England died. He was later canonized a saint, styled “The Confessor,”2 and it shouldn’t have been a surprise to anyone who knew him - he was much more focused on religion than on governing his realm. The government he left mostly in the hands of his competent Earl Godwin, and later Godwin’s son Harold. Edward had no sons himself, and - aside from describing some visions prophesying woe on England after his death - didn’t seem concerned about it.

King Edward, like most men in England, was an Anglo-Saxon. The Anglo-Saxons had invaded England perhaps five centuries before, but long before 1066 - historians still dispute how, but it happened - almost all Englishmen had come to identify as Anglo-Saxon. Fighting off repeated Viking invasions (most notably under Alfred the Great in the 880’s-890’s) unified England as one Anglo-Saxon nation. So, for all his unworldliness, King Edward reigned as a solidly native king.

It was claimed by William Duke of Normandy that Edward had promised him the throne after his death. There aren’t any independent sources for this promise, but it wouldn’t have been totally out of character for Edward to have made it. (When the promise had ostensibly been made, Godwin had been briefly in disfavor, and Edward’s known pro-Norman sympathies might have come to the fore.)

What was clear was that Edward couldn’t legally make that promise. The English monarchy was technically elective; kings were elected by their parliament, the Witenagemot or Witan3. They usually elected a son of the last king, but they didn’t need to - and besides, King Edward the Confessor didn’t have any sons4.

So, when King Edward died on 5 January 1066 - without seemingly taking any care for England after his death - the Witan met to choose the next king.

The Witan contained no partisans of William’s, nor anyone who - as far as we know - knew or cared about any such promise. What they did know was that William was threatening invasion, as was Harald Hardrada king of Norway. They passed over King Edward’s distant nephew Edgar Aetheling, the last of the ancient royal house, to elect - for not quite the first time - someone with absolutely no blood claim to the throne: Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex.

What King Harold did have was proven administrative and military ability. England needed that.

In all, King Harold held the throne for less than a year. His time was taken up waiting for the two invasions. Deciding William was the greater threat, he gathered both his trained soldiers (called housecarls) and peasant levies (called the fyrd) in Kent, waiting for William to strike.

William of Normandy was styled “the Bastard” - but only behind his back. He had been born illegitimately, and seized the ducal title by force of arms and constant war against his relatives and surrounding dukes. That seemed to set his character for the rest of his life: continual war. Admittedly, that wasn’t very unusual one among contemporary French nobles.

What was more, he had a longstanding interest in England. Normandy had sheltered Edward the Confessor before he came to the throne, and William continued to show interest in the goings-on of the court. We know he visited, whether or not Edward had made any promise.

And then, in 1064, two years before Edward the Confessor died, Harold was shipwrecked - we don’t know why - off Ponthieu, in northern France next to Normandy. The local nobleman kidnapped him; William invaded and rescued him. For a while, Harold was William’s guest; they went to battle together against the Duke of Brittany. And then, before Harold went home - according to what William and the Normans claimed later, Harold swore an oath on holy relics to support William’s claim to the English throne.

Whether that happened, we don’t know. Many historians think William tricked Harold into it by hiding the holy relics till afterwards; something like that would have been very much in-character for William. I don’t believe Harold ever said anything about it afterwards, one way or the other.

Regardless, when Harold accepted the crown of England, William promptly declared him an oathbreaker and started assembling an army to invade. What’s more, armed with the story of the oath, he convinced the Pope to officially bless the coming invasion5.

William’s invasion fleet was held back by contrary winds, stuck in port in Normandy. So, Harold was forced to dismiss the fyrd - their traditional time of service was ended, and they were needed at home to bring in the harvest - before any battle was fought.

And then the other would-be invader - Harald Hardrada, King of Norway - struck in the north, at York.

Harald of Norway had a local ally: the traitorous Earl Tostig, brother of Harold. In 1065, the previous year, Tostig’s subjects had revolted against him when he doubled taxes. Harold and King Edward had thrown him out of his earldom; in anger, he went to Norway and urged King Harald to invade. Harald of Norway, an avid warrior, didn’t need much convincing.

As soon as Harold of England got the news, he marched his housecarls up north - with record speed, 185 miles on foot in only four days. With a few local levies who’d joined along the way, he met Harald of Norway by surprise at Stamford Bridge.

It is said in the Norse sagas about this battle that, before the battle, a rider rode in front of the English host and - in Harold’s name - offered the treacherous Tostig his earldom back if he would merely fight with the English in the battle. Tostig replied, what would be given to his ally Harald of Norway? The rider responded, only “Seven feet of English ground, as he is taller than other men.”

At that, Tostig refused, and the rider returned to the English line. Harald, impressed by the rider’s boldness, then asked if Tostig knew who he was; Tostig only then revealed it was his brother King Harold.

Then battle was joined. At the bridge itself, between the two armies, one Norwegian axman held up the English line at that chokepoint, slaying (it is said) forty Englishman himself before an Englishman floated under the bridge and slew him with a spear-thrust underneath. And then a heated battle ensued, but the English carried the day and both Harald Hadrada and Tostig were slain.

And then, while Harold and his men were feasting their victory in York, the dreadful news came: thanks to an unaccustomed friendly wind late in the season, William of Normandy had landed at Pevensey.

Again Harold made record speed marching south. He made the 200 miles in about a week, again gathering forces along the way. William was still around the seacoast, plundering the local countryside and waiting for a battle. Harold’s brothers Gyrth and Leofwine, who were with him, counseled delay, to let his men rest and wait for the local fyrd to rejoin.

But Harold insisted on fighting.

Historians don’t know why. Harold and his brothers all died in the battle the next day, and the survivors reporting on their council didn’t mention any explanation. Some historians suggest that Harold wanted to stop William’s plundering, while one historian6 suggests Harold might have been intimidated by the papal banner in William’s army signifying the Pope had blessed his conquest.

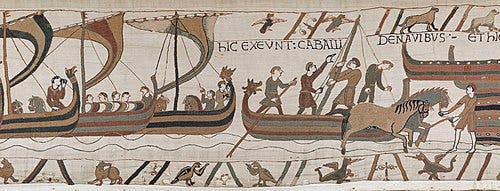

Regardless, battle was joined near the town of Hastings. There was no such storyteller at this battle as at Stamford Bridge, or perhaps no such stories. Unlike the Norse sagas, the Norman account of the battle was a tapestry, the Bayeaux Tapestry, essentially a cartoon manga of the invasion.

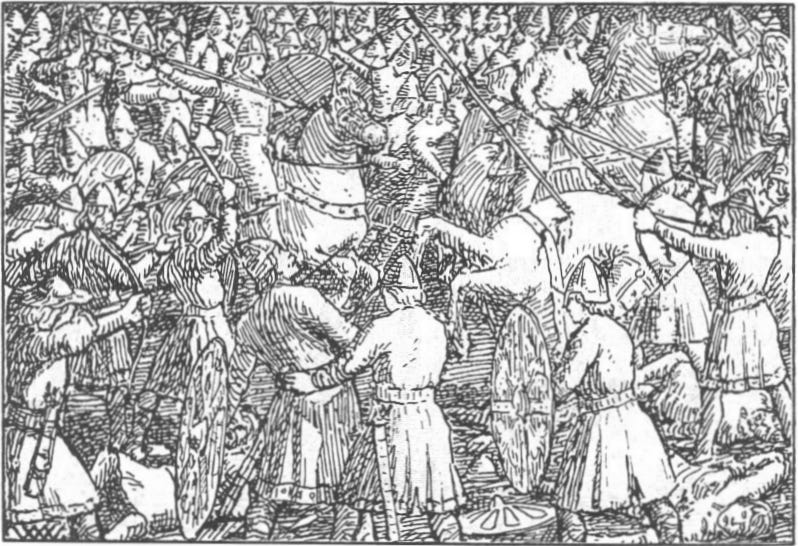

But the sober facts we know are: The English were on a hill, on foot, behind their firm shield-wall. The Normans, many mounted, charged the hill several times through a hot day of battle, and several times retreated downhill . The English shield-wall held through charge after charge... but then it broke to pursue the retreating Normans. King Harold regrouped them, but after some loss.

And then the next time the Normans retreated - historians suspect Duke William faked the retreat, to break the English shieldwall again. Regardless, they did break in pursuit, and the Normans turned on them with great slaughter. Harold himself was killed at this time, most likely hacked by four Norman swordsmen7.

And Harold came from the north and fought with him [William] before all the army had come, and there he fell.

-- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Thus King Harold fell, and the kingship of England with him. He had been an excellent general; he had done two seemingly-impossible marches and won one great battle - defeating perhaps the last great Viking host in Europe - in-between.

But, all those great deeds weren’t enough. He still fell in battle, and history took a significant turn with his death.

William of Normandy had won his great invasion. Henceforth, he would be styled William the Conqeror. I’ll pick up next week with how he reigned as King of England, over the kingdom he had conquered that day at Hastings.

...The ground was covered with corpses for a vast distance, stained with blood: they were the flower of the nobility and youth of the English.

-- William of Poitiers, “Gesta Guillelmi”

Continued in The Norman Conquest, Part Two

By the Julian calendar in use at the time; by the proleptic Gregorian calendar (the calendar we use today), it was 20 October 1066 - next week, when I’ll publish the second half of this post.

“Confessor” is a title accorded every saint who wasn’t martyred; I think it became a quasi-personal title of King Edward’s to differentiate him from the earlier King Edward the Martyr. The system of numbering kings of the same name only started after the Conquest, with William I the Conqueror.

The Witan wasn’t historically the ancestor of the English Parliament, which gradually accreted after the Norman Conquest. However, while Parliament was searching for precedents to claim new powers through the 1600’s, Parliament did frequently cite the Witan, including occasionally alluding to how they chose kings.

He didn’t have any daughters, either. It was doubted at the time, and ever since, whether he ever consummated his marriage.

What also helped was that the Archbishop of Canterbury had been irregularly elected and thus excommunicated. Some Eastern Orthodox suggest that the English church had been Orthodox before the conquest; there’s little reason, and the Great Schism wasn’t an accomplished fact yet at the time, but it might be true that the English church was more obedient to the Pope after the Conquest than before.

David Howarth, in his very good “1066: The Year of the Conquest.”

Contrary to popular belief, he was most likely not killed by an arrow in the eye; that idea most likely comes from a misinterpretation of the Bayeaux Tapestry.

Let me guess Evan, it all started when they came to Britain in small boats? ;o)