When I was a kid, I remember, under the radio in the dining room, I had a long shelf full of the Oz series of books. I remember I liked them a lot. But I don't remember much more about them, and unfortunately, they vanished sometime before I grew up.

Years later, in college, I decided to crack Oz open again and see how I liked it. I felt the individual episodes were still picturesque, in something of the same way I'd felt as a kid. But now, they felt much more shoddily pasted together. But - that didn't matter to me as a kid.

There're fourteen Oz books. Or twenty-three. Or thirty-three. Or forty. Or hundreds. The uncertainty is fitting. As I wrote earlier, when an author feels he has to write sequels, decay can set in. The sequels to Oz do indeed go downhill. Baum wanted to stop several times, but his young readers kept pleading for more. It might have been better for the story if he had stopped, or even if it wasn't continued after his death. By the end, he had written himself into a corner - and he and his successors continued going.

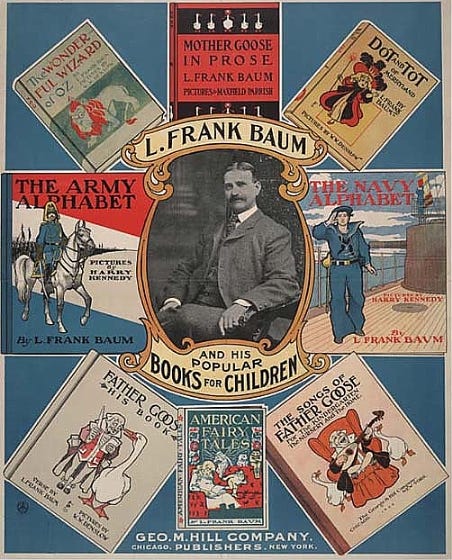

L. Frank Baum eventually wrote fourteen Oz books, from the famous Wizard of Oz through Glinda of Oz. He ended up crossing over Oz with nine other books he'd written, making twenty-three. At first, he meant the crossover with seven other books to be a grand finale for the series; then when he continued, he brought in the heroine from two other books.

Then, after Baum's death, his publisher commissioned Ruth Plumly Thompson to write nineteen more books (making thirty-three). Then after her death, seven more were commissioned, making forty ("The Famous Forty" as fans call them.) By that time, Baum's original books were out of copyright, enabling fans to publish myriads of unofficial sequels.

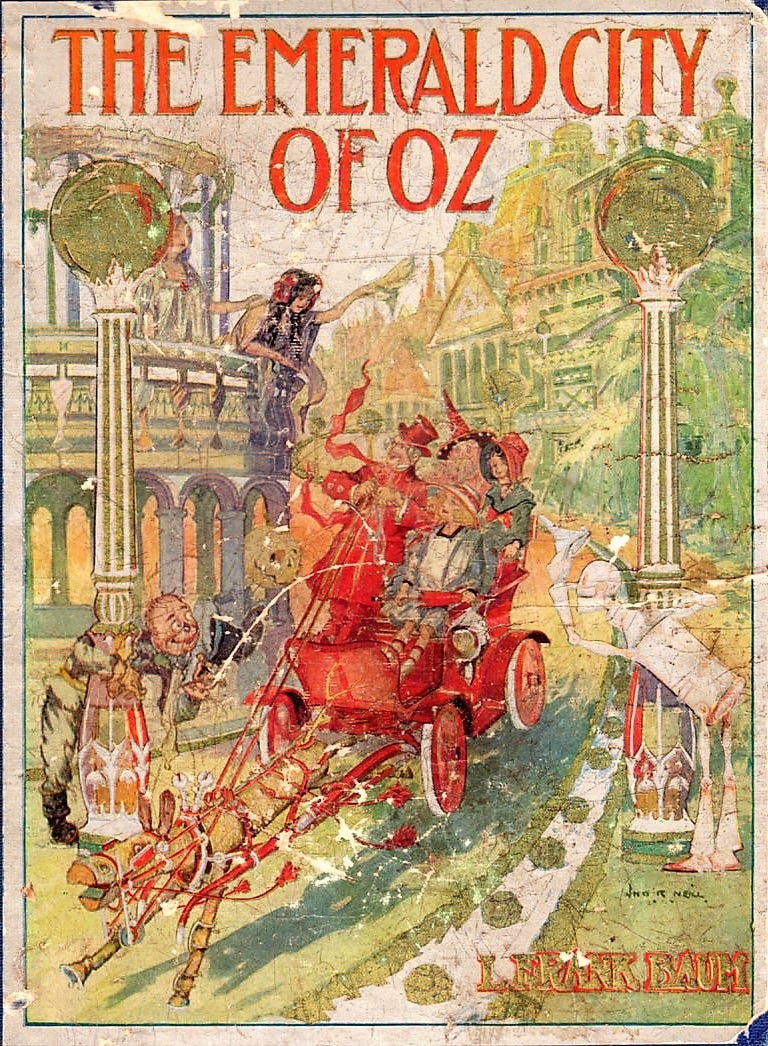

Oz changes dramatically after Wizard of Oz. At the end of Book Two (Land of Oz), the quasi-fairy girl queen Ozma is put on the throne, where she continues to reign through the rest of the series. We are informed it's an idyllic reign, though her actual decisions shown in the books are questionable at best, providing premises for many other stories. A few books later, we hear that everyone in Oz is immortal. Dorothy, after starring in several further adventures, moves to Oz permanently in Book Six (Emerald City of Oz, where Baum intended to end the series); as do several other young heroes and heroines Baum brings into later books.

The books are usually smaller scale than Wizard of Oz but similar in general concept. Dorothy, or Trot or Ojo or some other protagonist, might be questing to fix a magical accident or go home again or reach a destination. They usually travel through weird places we've never seen before, encounter magical trials which they unravel or are rescued from, and reach their goal through help.

It's a broad formula, and one that can be repeated if you don't care about developing characters or settings between books. Baum did repeat it for fourteen Oz books, and Thompson and his other successors after him. I liked it a lot as a young kid, and even as an adult I still remember some of the individual places and episodes as charming - like Princess Langwidere’s many heads, or Glinda and the Three Adepts singing the sunken city up out of the lake.

But - the story tying together those episodes is often weak. It becomes even weaker when you look at the near absence of story tying the series together.

Literature professor Paul Hazard, in his 1932 book on the history of children's fiction, pointed out that children have flocked to books with themes and plots way over their heads - like Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver's Travels - because they contained so many exciting events. He isn't wrong. For all its flaws, the Oz series gets the exciting events quite correct. All the random wayside encounters give more exciting events. The random quests that keep piling on each other, and the incoherent nature of Ozma's rule, provide openings for more exciting events. The new protagonists are new hooks for more exciting events that wouldn't happen to Princess Dorothy now peacefully living in the Emerald City (or Trot, or Betsy, or Ojo, or any other previous protagonist now living there.) And when the old protagonists do show up, either they steal the stage from the current protagonist, or they stand back without solving the problem at the cost of their previous characterization.

Baum tried to involve his previous characters. In Patchwork Girl of Oz (book 11), they enter in halfway through to help our protagonist on the last half of his quest, but that's something of a letdown because it means the protagonist doesn't solve his problems himself. In Lost Princess of Oz and Glinda of Oz (books 10 and 14), Ozma is kidnapped - but that introduces new questions about her competence as ruler of the country. I'm not surprised that Ruth Plumly Thompson largely abandoned this for more random quests with new protagonists or previous side-characters.

The consistency of the world suffers - but that isn't the point. I didn't care as a kid. As Professor Hazard points out, kids enjoy Gulliver's Travels; everything they got from there is still well-done in Oz.

While Baum was writing Oz, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was continuing his Sherlock Holmes series under similar pressure from fans. He'd hoped to abandon it in 1890, and again in 1893, but - just like for Baum - pressure from fans and a lack of success for his other books made him return.

But Doyle had an easier time than Baum. Holmes, a detective, can easily solve completely different cases in different stories without any continuing characters besides himself and Watson. The world is the real world, with whatever additional naval treaties or manor houses are required. Doyle doesn't need to keep details straight, and indeed, even the location of Watson's old bullet-wound changes from story to story. The quality of the mysteries does go downhill, but it isn't as visible. And, short stories make it easier to skip over the worse stories for better.

A better comparison to Baum is Brian Jacques. He lived long after Baum, and I don't believe he tried to stop his Redwall series midway through, but the premise of the stories is much closer. Like Oz, Redwall is a very-long-running kids' adventure series set vaguely around one location (Redwall Abbey, in the fictional Mossflower Woods.) Like Baum and Thompson, Jacques kept writing new adventures with new protagonists, with lots of exciting happenings for kids to like. Also like the Oz books, I liked the Redwall books as a kid (several years after I grew out of Oz the first time) - but by nine books into the series, they started feeling repetitive. Of course we get another young protagonist on a quest, who gains the magical sword of Martin the Warrior; of course an army of "vermin" try to attack Redwall... and the characters start feeling similar too.

But Jacques' world never felt as tired and stretched and indeterminate as Oz. The Redwall quests happen across generations, while the Oz quests all happen in the same immortal "generation." There's never a single ruler over all Mossflower (except briefly at an early date, in Mossflower), so random warbands are expected; while the random magical adversaries in Oz make me wonder how good or effective Ozma is as a ruler. There's next to no magic in Redwall, while the magic in Oz has whimsical rules so we often can't guess how seriously to take an event. And, protagonists of Redwall novels usually live out a long life and retire or die before the next novel happens, while protagonists of Oz novels usually collect in the Emerald City and leave us wondering why they don't do visible things. Even as a kid, I wanted to read more about the Oz characters I'd already encountered, since they were obviously still around!

In short, Jacques tried to write the same sort of series Baum wrote. From a kid's perspective, they both succeeded, because they had a lot of good characters and exciting happenings. From the perspective of me slightly older, they both partly failed because we get tired of the repetitive stories. But from a larger story perspective, Jacques succeeded much more than Baum because he made a setting where his long-running quests and adventures actually hang together and make sense.

I expect Baum could have planned it out better if he'd tried. Though, I'm not certain, because to my knowledge he never did try to build a setting where many stories could take place. He certainly didn't with Oz, as he didn't plan to write so many books until he'd already locked himself into a lot of his worldbuilding.

Once he did, I'm not sure what he could have done aside from telling different sorts of stories. Princess Dorothy living in the Emerald City can't lead the same sort of story as farmgirl Dorothy from Kansas. When the Scarecrow briefly sort of tries (in Book 8, Scarecrow of Oz), the effect is half-comical thanks to how (thanks to magic) he's never far out of reach of his powerful friends. Medieval minstrels could send King Arthur's knights on individual quests, but that was because King Arthur never had magical evesdropping or teleportation.

Oz succeeded anyway, in that kids like it. I certainly did as a kid. I'm not faulting it there. That was what Baum was trying for.

But as I look back on it, I see it failed to be something more - not because of anything in the stories, but because of how they were set up and put together.

Another such case is Hugh Lofting, who wrote a Dr. Doolittle book a year from 1922 to 1928, when he sent Dr. Doolittle off to the moon and had Thomas Stubbins come back to Earth without him. After that there was a five-year gap before he wrote Dr. Doolittle's Return. Apparently Lofting had intended Dr. Doolittle in the Moon to bring the series to an end . . . but he didn't succeed.