Some Thoughts on Sequels

When you write a story people like, they want more.

It's the annoying cry every fanfiction writer knows ("when's the next update?"), and it's the same cry every professional novel writer has heard. Right after Tolkien published The Hobbit (very loosely set in what was then the far future of Middle-Earth), he was besieged with cries for more. Fans want more from the author - but also, they want more in the same story. They want more of the characters and setting they've come to love. They want a sequel.

Unfortunately, if the first story was a good one, there usually isn't more of the same story. That story was told. Even if the author writes an interequel set in the middle of the first book, or a sequel set after it, they're different stories. Catching Fire is not the same story as Hunger Games. Even if it continues the same story in a series with the same characters, it's a different story: the characters who've grown in the first story can't retread the same growth in the second. In Two Towers, Frodo has grown from who he was in Fellowship of the Ring.

(Movies often have this problem too, as well as other problems such as hiring back the actors who played the main characters last time. But I'll be talking about novels since that's what I'm more familiar with.)

Meanwhile, fans' expectations have been raised. They like the characters; they like the story; they want more.

Maybe the author ignores this and goes on to write something else. That's a legitimate choice; authors don't need to give in to the fans. But, if so, there's nothing more to say. Or, maybe the author has more of the story already in mind and was dropping Chekhov's guns for it in the first book. That would forestall some challenges - but still leave a lot of challenges about meeting the fans' raised expectations.

The simplest way to give readers what they want is to retread the same ground; give them a new story exactly like the previous story. This's frequently done in kids' books. I remember enjoying Encyclopedia Brown and Magic Tree House as a kid, where every book is pretty much exactly like the ones before and after it. To do this, they make sure to have no continuing plot arcs (except for one mystery in the first several Magic Tree House books), and no character growth. Encyclopedia Brown solves his mysteries, and Jack and Annie travel through the past, without changing as people. Nothing really has a lasting effect on them, and nothing lastingly changes in the world around them.

(This doesn't only happen in children's books - we see largely the same thing in Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes series. But there're some other unique issues in Doyle's case, which I'll talk about later.)

If something big does change in the world around your character, that'll also eventually keep you from telling the same story again and again. Edgar Rice Burroughs ended up here in his Barsoom series. After John Carter has become unchallenged Warlord of Mars, he can't be having the same sort of swashbuckling adventures again. So, Burroughs decides to tell the same sort of story with new protagonists: first Carter's daughter, and then some totally unrelated people. (He does eventually return to Carter twenty years later for two last stories, which I haven't read.) But even so, even though John Carter's circumstances and title change, he himself doesn't change as a character.

In the final reckoning, I think, all these are poorer stories for their static protagonists. It's not bigger challenges that make a story good, so much as how they affect people we care about. Colorful explosions can make a happy fireworks show, but if people we care about are in the firing line, the fireworks can become a harrowing bombardment. To avoid this - to tell a sequel about the same protagonist, without reducing them to a static character unaffected by events - you'll need to strike out in new directions. Megan Whalen Turner realized this after The Thief. She realized that she wanted to stretch her protagonist Gen in new directions rather than keep telling the same story again and again, so she decided that at the start of the second book he'd have his hand cut off. That worked; the second book is nothing like the first, and much better. After that, Book Two changes so many circumstances that the series keeps developing in new directions.

Dorothy Sayers also did this very well in her Lord Peter Wimsey mystery series. The first book, Whose Body?, is largely a conventional mystery. The detective, Lord Peter, has some interesting character traits (such as shell shock from World War I service, and a habit of interesting literary quotations), but they don't really impact the plot. But then, Sayers decided that the sequel would involve a murder in Lord Peter's own family circle - and Lord Peter blossomed as a character. Several books later, Sayers had him fall in love, and only then realized that both he and his beloved Harriet Vane would have to grow into deeper and more complex characters if they were to end up together. These were the first detective novels to have such multidimensional dynamic characters, and I love them for it. When I recommend them, I actually advise readers to skip Whose Body? and start with Clouds of Witness (the murder in his family circle) or even Strong Poison (when he falls in love).

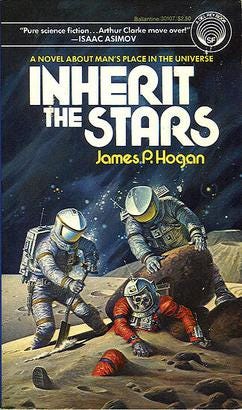

Not all books even allow for this sort of sequel, though. When you can't just add a new adventure or character clash after the previous one, things can get more complicated. I can't help thinking here of the sad decline of James P. Hogan's Giants series. The first book, Inherit the Stars, was an excellent scientific mystery story: a fifty-thousand-year-old apparently-human body is found on the Moon; where did it come from and how did it get there? After many twists of prehistory and scientific mysteries, Hogan gives us an ingenious and satisfying solution. But after that, when he wanted to write a sequel with similar twists, there were fewer places left to go: Gentle Giants of Ganymede was good but nowhere near as good as the first book. And then there were still fewer left for each subsequent entry in the series, as the mysteries and solutions got weirder. I strongly recommend the first book; the second is worth reading, but I wouldn't advise continuing after that.

Or, you can write a sequel in a completely different genre. Sherwood Smith's Crown Duel, an adventure involving a succession war in a fantasy country, was followed by Court Duel involving intrigue at the new king's court. (I enjoyed them both, but they felt like very different books.) Even further removed, after writing her marvelous middle-grade novel Enchantress from the Stars, Sylvia Louise Engdahl followed it up with a very different older-YA novel about the same protagonist, The Far Side of Evil. (The first book was great; the second was decent but very different and nothing special.)

The epitome of this might be C. S. Lewis's "Space Trilogy". The first book, Out of the Silent Planet, was a popular science fiction book when it came out, with a philosophical message about humanity's place in the universe. Lewis started a sequel involving inter-universe travel, but he abandoned it in favor of, essentially, a novelized theological discourse around sin and holiness: Perelandra. And then, the third volume was (as the subtitle says), "A Modern Fairy-Tale." Every book in the trilogy is in a totally different genre; I enjoy all of them, but in very different ways.

This can accentuate the problem where fans of one book might not like the sequels, especially given the expectations they come in with. When I first read Court Duel, I thought it was a letdown. Engdahl, on her website, even warns young readers away from The Far Side of Evil, saying "I regret having connected the two novels by using the same heroine in both, since they are independent stories." It's for a different and older audience, she explains. Their expectations will be disappointed - and readers who'd enjoy Far Side of Evil won't find it if they think it's merely a sequel to Enchantress from the Stars.

(But then, the same thing can happen the other way around. As I said, I warn people away from starting with Whose Body?. Or even without authors noticeably deepening characters, the sequel can just be so much better. Hundred Cupboards is a good YA book, but its sequel Dandelion Fire is just so much better.)

But an author might not want to do any of this.

"There are two places to stop a series," C. S. Lewis once said to a fan disappointed that he hadn't written more Narnian books, "before people are tired of it, and after." He had written several sequels, and his fans were still hungry for more, but he didn't want to write more. Sometimes that tiredness comes faster; Lewis didn't want to even write one sequel to his Screwtape Letters because he was tired of thinking from Screwtape's viewpoint.

(Or an author just might not have any more stories in mind. Engdahl says she'd like to write another sequel to Enchantress from the Stars, but "I don't have any ideas for key events that would make a story compatible with the premises I've established" in that universe. Similarly, when readers begged Clare Dunkle for a sequel to her By These Ten Bones, she answered that "These characters have gone through enough trouble, and a new book would bring more trouble into their lives.")

We can see this problem more clearly with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. After writing two novels and several volumes of short stories about Sherlock Holmes, he was tired of Holmes and exasperated that these stories were so much more famous than his preferred historical novels. (I haven't read many of his historical novels, but White Company is good.) He introduced a new criminal mastermind, Moriarty, to promptly kill Holmes off... but reader insistence made him resurrect Holmes a little later and write still more stories. (Despite Moriarty's fame in the popular mindset, he only shows up in one short story and the background of a later novel. He kills Holmes mere pages after his first mention without having ever shown up onstage.) There are a few gems in these later stories (like "The Red-Headed League"), but we can see Doyle's standards slipping as, exasperatedly, he writes more and more sequels about a character he no longer likes. "The Solitary Cyclist" has impossible clues, and "The Lion's Mane" and "The Creeping Man" involve drugs not found in reality. (I'm not even mentioning "His Last Bow" which was written out of patriotic fervor amid World War I.) Also, even before Reichenbach, we see Holmes starting to get flanderized: some of his traits like his chemical research and astronomical ignorance move offstage or get totally dropped.

What's more, although Hound of the Baskervilles is a fun and memorable story, there're lots of dangling clues and Holmes scarcely appears for a lot of the book. I've read one fan work analyzing the book like a case record, to prove that Holmes overlooked the "real culprit." That's because Doyle originally wrote it as a supernatural thriller and only later - exasperatedly - revised it to include Holmes and no longer have an actual supernatural hound. Doyle had written too many sequels about his fan-loved detective.

I've given a lot of examples of different sorts of sequels. The authors are trying to do different sorts of things and satisfy different sorts of fans. So how do we tie these together?

One common thread is, do something you like with the sequel (unlike Doyle), that's tied in some way not just to the previous book, but to what readers liked about the previous book. Engdahl's Far Side of Evil does relate to the Service and galactic civilization, but it loses the feel readers of Enchantress from the Stars liked. Meanwhile, Lord of the Rings is very different from The Hobbit, but it kept enough of the Hobbity feeling that readers still liked it.

But then again, not every sequel can be everything to everyone. Perhaps something like the John Carter novels come closest in that just about everyone who liked the first novel will like the sequels. But that's only possible because Carter and most other characters are static in the first book. Once Bilbo Baggins has learned to step outside his comfort zone and love adventure, you can't go back to repeat The Hobbit again. And even with static characters, it can get tiring to readers who might eventually want actual character development and progression beyond the bits we see.

So, perhaps the moral is for the author to ignore the fans' calls for a sequel, or at least to deprioritize them. The author should write according to his art, to the same art that gave him the first novel. If he's a true follower of that art, and if the art is a true art, then readers will like his next books no matter what sort of sequel or non-sequel they are.