Solution Unsatisfactory

When your world offers no visible way out

It's been years since I read Robert Heinlein's chilling short story "Solution Unsatisfactory" about an alternate-history version of World War II, but it's stuck with me. The story presents a problem, but no good solution. Every solution offered is unsatisfactory. A global dictatorship has arisen, against a threat of world-destroying war, and the narrator is stuck in the end looking around wondering what better solution could've come.

The question is - when the physical laws of the world are set up against humanity, either humanity's existence or our living in good societies - in that situation, how should people proceed? To use a term some modern philosophers have coined, in situations of "existential risk" - when our existence is in some way at risk - how should people proceed?

Then last year, I noticed that the same questions get explored in David Brin's chilling short story "Thor Meets Captain America" (which's also stuck with me since I first read it years ago). It's got a very different plot and message, but it's also about a (very different) alternate version of World War II where the laws of the world set up every solution to be unsatisfactory. But Brin gives an answer anyway.

Heinlein does give one answer in another book. Last month when I was reading his novel Space Cadet, I noticed it was set in a world closely parallel to "Solution Unsatisfactory." There, they've happened upon an answer to the problem. But, when I look closer, it's still unsatisfactory to anyone who doesn't happen over it.

Heinlein and Brin's different answers resonate with their different views of reality and the different themes that play out in all their works. And, if we set them in dialog with each other, we can get at some even deeper questions - about how to tell a story about a protagonist living in a world marred by problems he can’t fix, and about how to react ourselves if we end up in similar situations.

The title Heinlein's publisher gave to his story - "Solution Unsatisfactory" - applies to his story, and also to Brin's. Any solution within the stories is fundamentally unsatisfactory. In Brin's story, our hero is killed while fighting for a losing cause. In Heinlein's, our protagonist survives, but the world falls under an inevitable but unstable dictatorship.

This's because the authors set up the worlds that way. In both stories, there's a discovery with massive consequences that demonstrates how the universe's rules are unstable for societies. And, the characters are forced to react to this.

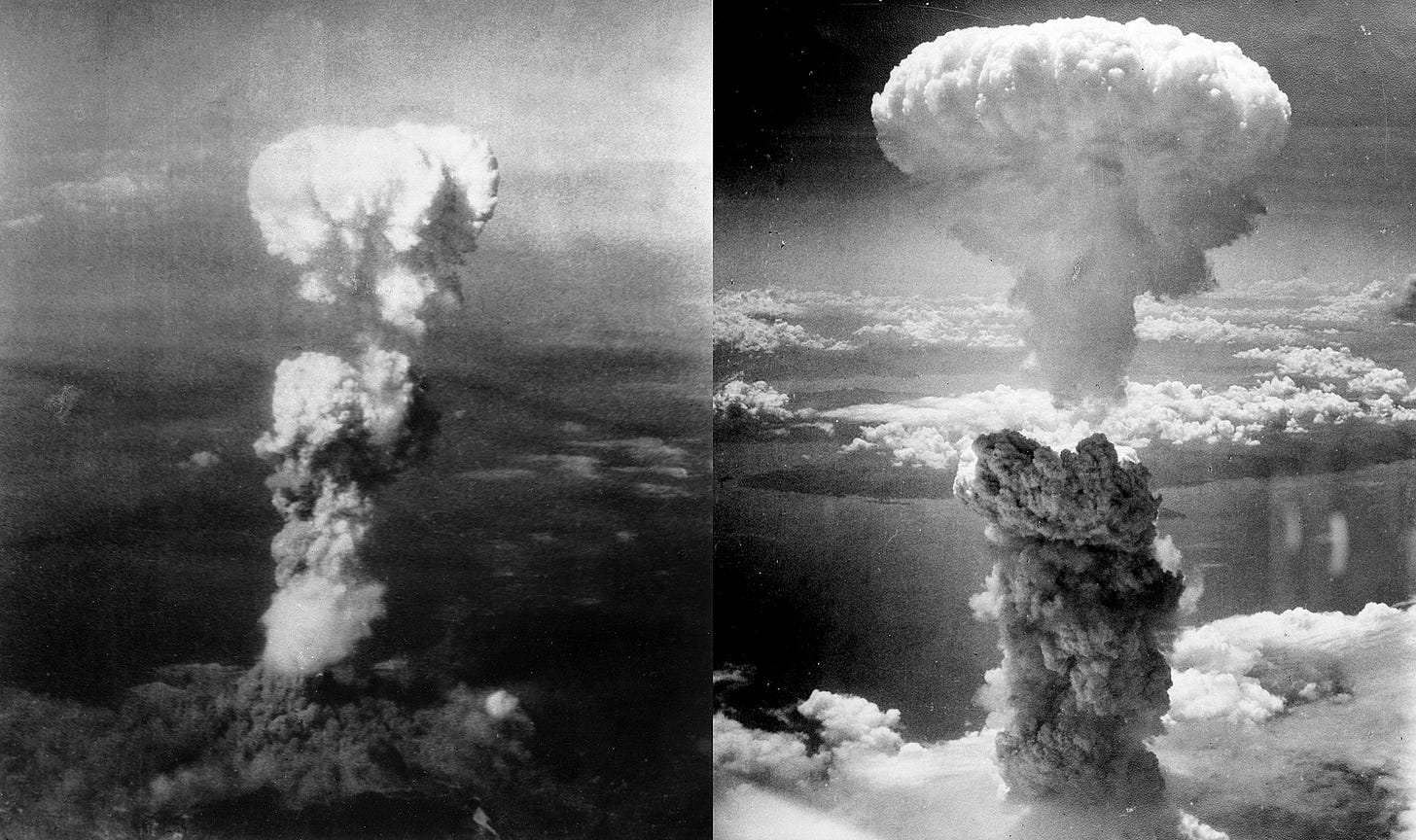

Written in 1941, Heinlein's "Solution Unsatisfactory" anticipates the atomic bomb. But, he paints it as much more powerful and disturbing than the early atomic bombs actually were. In his story, a few bombers distributing radioactive "Dust" over... say, World War II Berlin... could kill literally every person and animal in the city.

This instantly ends World War II, but it makes it obvious that the "Dust" is deadly enough that something needs to be done before another war destroys the world. In reality, a nuclear war in the late 40's would have been entirely survivable - but in Heinlein's story (written before the actual atomic bomb!), it wouldn't be.

Our protagonist is an aide and confidante to (the fictional) US Senator Manning, who sees this and recognizes he needs to stop any other country from using Dust. This story was written before spy satellites and before even radar was publicly known, so he convinces the American government to forbid any other country from flying airplanes. There's one brief war - the USSR had just started making Dust itself - but the world narrowly escapes because the USSR wasn't entirely ready for a war yet.

Then, to ensure this plan stays stable, Manning founds an international "Patrol" insulated from political pressure to enforce this under the threat of using Dust. A few years later, he uses the Patrol to become world dictator.

Our protagonist doesn't like this, but he keeps asking throughout the story, what else could have been done? Manning at least feigns reluctance to become world dictator, but he keeps saying he's forced at each step. And, in a world with this Dust and no radar, it's hard to see any other course. Without Manning, in all likelihood, they probably would've gotten more - and much worse - wars with Dust - and from 1941's vantage point this does sound plausible.

But this solution is, still, unsatisfactory. They get the dictatorship; our protagonist guesses they'll get more wars anyway after Manning's death. The story faces us with the question: In a world with every solution unsatisfactory, how should people respond?

Brin's story is more fantastic in the literal sense: amid World War II, the Norse Aesir gods, or something like them, have appeared to help the Nazis - and now the Nazis are winning.

But, it asks the same question. Just like Heinlein wrote about the discovery of Dust which destabilized the world, Brin writes about the discovery of something that brought these Aesir here. And the real problem, it turns out in the story, is not the Aesir themselves - even as they're bringing the Allies down to clear defeat - but that something which brought them here.

It's a huge spoiler; the story is well worth reading once without it before you learn it.

If you feel you might want to read it, please do so now before you continue here.

One Amazon review of this story protests - referencing the title - "I feel quite let down here. This had some potential but where the hell is Captain America!?" Yet, the whole point is that there is no “Captain America” equivalent to the Nazis’ Aesir. It turns out the Nazis summoned the Aesir through mass murder and necromancy. That's how they're winning the war.

In the story, other countries could in theory use this necromancy... but just like Dust-on-Dust wars in Heinlein's story would destroy the world, so would mass-murder-on-mass-murder wars here. But without it, just like the Dustless Germany in Heinlein's world, the Allies are inevitably losing. The war has gone on for decades (long enough for the Allies to build a space station), but their defeat is by now obviously inevitable.

But as our hero says at the end, after learning how the Aesir came to be:

Better America and the Last Alliance should go down honorably than be tempted by... this horrible way out. For if the Allies ever adopted the enemy's methods, there would be nothing left in the soul of humanity to fight for.

Just like America falling under Senator Manning's dictatorship in Heinlein's story, it would have been a larger defeat: an unsatisfactory solution.

The stories offer unsatisfactory solutions: creating a dictator, or our own mythic heroes, at horrible cost (whether dictatorship or mass murder). What are better solutions?

They don't offer any.

In Brin's story, the Allies are fighting hopeless delaying actions. In Heinlein's, every step from the discovery of Dust to Manning's dictatorship seems inevitable. One review of Heinlein's story says it's unrealistic how many people give into Manning's proposals - but within the world of the story, even all his suggestions couldn't avert nuclear war.

Brin does offer tantalizing glimpses of hope: submarines can already sail in depths that discomfit the Aesir, and the space station's mere existence sends the Nazis into paroxysms and disrupts all their astrology as it sails above all their powers. But they no more than annoy the Aesir. There is not enough time for this technology to actually give more than wisps of hope. Later, Brin wrote a sequel to this story as a graphic novel (with vastly-inferior writing quality), where the Allies are conquered offstage before the sequel begins - and that's no surprise; we could guess it from the original story.

Heinlein doesn't even offer this much hope in "Solution Unsatisfactory." The only solution he suggests is to destroy the Dust itself, or destroy airplanes - but both of those are impossible. Technology, which Brin places tantalizing glimpses of hope in, is itself the problem for Heinlein: people aren't able to handle it in a survivable manner. But even destroying it is impossible, because someone else (like the USSR) will be producing more Dust shortly.

Heinlein's protagonist ends up cursing the entire concept of war, because he can't think of any way out from civilization being annihilated by Dust. But that's all he does. He stands by Manning's side through the whole series of events leading to his dictatorship, without ever trying to stop anything. He is an onlooker to the story. He would doubtlessly protest he didn't have any better options. But that leaves him a mere onlooker to one inevitable unsatisfactory solution.

Heinlein does appear to offer more hope at a solution elsewhere. His novel Space Cadet is set in a future where something a lot like Manning's international Patrol worked. The Patrol has authority over all spaceships, and a monopoly on atomic bombs, which it reserves the right to drop on anyone who's threatening to build "weapons of mass destruction." Inside the book, it's been in existence for generations and kept its mission intact.

Space Cadet was published in 1948, seven years after "Solution Unsatisfactory" and three years after the real-world atomic bombs were unveiled. At the time, despite military officers knowing the contemporary atomic bomb's limitations, the public still viewed it as fearfully as if it was the Dust from "Solution Unsatisfactory." There were still vague real-world hopes of putting them under UN control, but challenges were making that less likely - both resistance from inside the US government and distrust of the UN. Also, though it wasn't publicly known, the Soviet Union was well on the road to building its own atomic bombs.

Inside the story, Heinlein doesn't give clear steps to getting to this Patrol. He references officers in the Patrol's past who tried to (like Manning) become dictators, but they were stopped by heroic other officers who have been commemorated ever since as creating "the Tradition of the Patrol." In the story, as we read of our protagonist going through boot camp as a cadet, we see the Patrol takes great care to make sure every officer-in-training believes in that honorable Tradition.

The narrator for "Solution Unsatisfactory" does allow for the possibility of something like this Patrol: "Had Manning been allowed twelve years without interruption," he says, building this honorable Patrol "might have worked." But - because of parochialism - he did not get that time. The Patrol was not established on that honorable a foundation.

Any of Heinlein's characters from Space Cadet would not have allowed either war or a dictatorship. They laud their predecessors who gave up their lives to prevent Mannings. There were people like that in "Solution Unsatisfactory"; our protagonist mentions in passing their "unfortunate affair[s]" and "wholesale dismissals." Brin's protagonist, who gave his life on "a hopeless attempt," would have fit right in among them.

But, they all failed. They knew they would fail.

Brin gives us the story of the hero who dies; Heinlein gives us the story of the practical man who isn't willing to be a hero in a lost cause.

Elsewhere (in Space Cadet), Heinlein reaches into the world he sets up to give a convenient backstory to give his world a better solution. From a point of view inside his world, this might look like a miracle: an intervention from outside the world by its author, to save the world from destruction. In the real world, a miracle is exactly what I and many others say is the only ultimate way to a satisfactory solution to many otherwise-unsolvable dilemmas.

Of course, just like characters can't step back and wait for their author to solve their problems, that still does leave the question of how to respond while the problems are still unsolved.

And, absent something from outside the worlds they've set up, both Heinlein and Brin leave us with a "solution unsatisfactory."

But there’s more I have to say on this subject; I’ll be continuing in Part Two next week…

Note that Heinlein told the story of one attempt at a Patrol dictatorship in his story "The Long Watch," about the martyrdom of John Ezra Dahlquist, one of the Four saints of the Patrol. It was published in his collection The Green Hills of Earth, but I don't think it's really part of the Future History; Space Cadet, at any rate, certainly is not.

I liked this article. Thanks Evan!