Short Reviews for November 2024

Space Doctor, Harp of Imach Thyssel, Pox Americana, Kon-Tiki

Space Doctor, by Lee Corey (245 pp; 1981)

Who should read this? Fans of Golden Age sci-fi.

This reads half as a Golden Age book after its time. Spaceflight is being carried out by a large corporation (run by our protagonist's old friend), but our protagonist (brought in as on-site doctor in the industrial space station) has something of the same zeal and sense of possibility.

But, that possibility is put to work in the details. We see our protagonist not building new inventions to do new things, but building up logistics and procedures to save lives amid the effort of building a space presence. Plus, he has a character arc. This's one way I wish the Golden Age could've developed. We've got the same brimming-over zeal and something of the same possibility still there, which has been lost in many modern sci-fi tales.

Unfortunately, this isn't a deep or long book. It's short enough there's little there beneath the surface. It's hard for me to even identify how much of Corey's description of industrial construction in space has been obsoleted by advances in computer tech. But, that surface gives you enough to be metaphorically splashed with - and to me, it's fun.

The Harp of Imach Thyssel, by Patricia C. Wrede (240 pp; 1985)

Who should read this: People who want more fantasy flavor and don't mind lack of driving the stakes home.

I read this back when I was in college, and I don't remember much of it from there; upon rereading it now, I'm having trouble finding much of it sticking in my mind now either.

This's disappointing. There's significant potential in the premise. Our protagonists find a super-magical harp and need to figure out what to do with it, while evading pursuers trying to steal its power. But, it fails.

Primarily, I think, it fails because we don't feel the power of this super-powerful magic harp. Until the end, we see its magic throbbing as its strings are plucked, but it never does anything that couldn't be coincidence. Our protagonists barely risk using it (sensibly enough), and there're stories of it causing disasters in the past, and two separate groups of enemies are after it for their own purposes - and I'm told all this, but none of it sinks into me as I'm reading.

In part, I think, that's because our protagonists don't know enough of the threat to talk about it. But also, what we do see of the magic doesn't convey any risk or threat. At least, it doesn't to me the reader, even though it seems to convey it to our protagonists.

What we get instead is interpersonal drama against the backdrop of this looming threat. In the end, I didn't think this book worth reading.

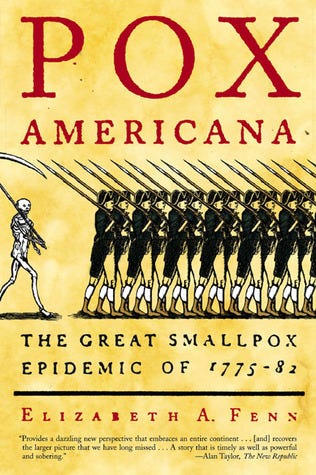

Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82, by Elizabeth Fenn (384 pp; 2001)

Who should read this? People who like digging into parts of history usually in the background, and who don't mind reading tragedies.

This history of the devastating, continent-sweeping smallpox pandemic of the 1770's-1780's is divided in two parts: the account of smallpox in the American Revolution, and the clues to its devastating impact on the American Indians, reportedly killing ~90% of many tribes or nations.

Smallpox hadn't been established in America outside Philadelphia, so most Americans were vulnerable - but not most British soldiers. It was perhaps smallpox that stopped America's attempt to conquer Canada, and perhaps smallpox that ruined royal governor Dunmore's attempt to free slaves and make them into a new British army. But, after Washington innoculated the regular Continental Army at Valley Forge, it never risked destroying the Patriot cause.

But Indians remained vulnerable - all the more so because of their inexperience at nursing patients, and (the author guesses based on recent studies) their genetic immunology. Whole nations perished; the Hudson's Bay Company had to push inland because their middlemen were now dead; the Sioux conquered the plains because their settled neighbors were now dead. But aside from a few long-after interviews with elderly Indians, we can only hear of the fringes, because only people at the fringes were writing.

I'm struck by both parts.

Kon-Tiki (color edition for young people), by Thor Heyerdahl (165 pp; 1975)

Who should read this? Fans of tales of exploration and adventure. I read the young people's color edition because that's what came into my hand; I imagine any edition works.

In the late 40's, Thor Heyerdahl - an zoologist and amateur ethnographer - had the idea that Polynesia had been originally settled from South America, using the same balsa rafts that the Indians were known to use. To prove it possible, he and some others built a raft following Indian models, and made the voyage themselves. This short book tells the story of their successful trip.

Nowadays, Heyerdahl is considered a pseudoscientist who denied the Polynesians' ability to navigate against currents. Even in his day, the scientific establishment rejected him. Subsequent genetic analysis has shown Heyerdahl's theories at least somewhat wrong: most Polynesians are not descended from American Indians. But, we know there was some contact: the yam appears in both places. And, later studies have apparently shown some American Indian genetic traces after all - so perhaps there were some raft journeys like he made?

However, Heyerdahl doesn't major on his ethnic theories in the book; this's primarily a tale of adventure and the possibility of recreating the past. He and his comrades read as stunningly amateur in everything except their knowledge of Peruvian Indian raft-building - but that carries them through.

It was a beautiful adventure, but also stunningly daring. Beforehand, no one had thought a balsa raft could survive such a long voyage - but they dared to try it. Beforehand, no one knew what it was like to sail so low to the ocean - Heyerdahl tells of stunning sights, some of which are attempted to be captured in beautiful pictures here. This's a worthy addition to the annals of exploration.