In 1870, the German Army swept into France - another Great Power of Europe - and within a month and a half was at the gates of Paris, with the French Imperial government overthrown and French power all but vanquished. Before peace was concluded, another revolution would shake Paris, and the loose North German Confederation would turn itself into the German Empire. The eventual peace treaty would see France shorn of two provinces and weighted down with an indemnity.

That war, the Franco-Prussian War, is a story in itself. But what I'm thinking about now is the reaction in British and American minds afterwards. Suddenly, a Great Power of Europe had been defeated in mere weeks by something that was yet barely a nation. The much-vaunted French Army had proven itself hollow. Would other armies do the same?

This spurred a genre of fiction: "Invasion Literature."

The genre started with George Tomkyns Chesney's 1871 The Battle of Dorking, published in a respectable British political magazine just after the Franco-Prussian War had concluded. In it, an enemy (unnamed but clearly modeled on Germany) sweeps across the Continent and invades Britain, where an unprepared and ill-managed British Army goes down to swift defeat in the eponymous town of Dorking. We see this from the point of view of a patriotic Army volunteer who's horrified at the mismanagement and then at the harsh peace imposed on Britain. In the end, his message is loud and clear: Britain should have prepared better for an invasion!

This became stupendously popular, and sparked a large genre. Most titles here are justly forgotten today, but they were quite well-read in their day. It was so common that famous humorist P. G. Wodehouse parodied it in his The Swoop! where England is simultaneously invaded by nine different powers including Switzerland. The best-known work from this genre - perhaps the only such work still popular today - is another unusual takeoff: H. G. Wells' War of the Worlds where the invader is not Germany but Mars. Still, Wells made use of many invasion literature tropes; the Martians would find British defenses just as unprepared as Chesney's nameless human invaders had found them.

Invasion literature was less popular in the United States, separated from Europe by sea. However, it did cross the ocean. For one major example, H. Irving Hancock's Uncle Sam's Boys depicts a transoceanic invasion by Germany, just as unexpected as in any British title and initially just as successful... though unlike in Chesney or even Wells, that invasion is eventually defeated by American power.

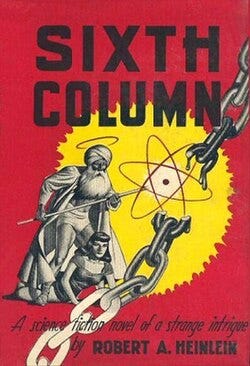

The tropes of invasion literature did continue in some sense, but the genre changed. For example, we can see Robert Heinlein's 1941 Sixth Column in the same genre... but there are differences. The invasion itself (by an unnamed Asian power clearly modeled on Japan) happens offstage as the book opens; the body of the story shows our protagonists fighting back with ill-described technobabble "science."1 Unlike Chesney, Heinlein (and Campbell who commissioned his outline) doesn't have anything to say here about how America should've prepared.

Invasion literature isn't focused on plausibility of details. Chesney doesn't name any foreign power, talk about how British logistics got snarled, or explain the invader's logistics. He barely even explains how the invader defeated the Royal Navy - which was, historically, what stopped Hitler from invading England in World War II. The American titles are even worse on this score, throwing logistics completely out - a fleet that was historically barely able to cross the ocean to the American coast is here launching a full-scale invasion!

What matters is the message: this can happen here. Peace is not to be taken for granted. You need to prepare for war.

After France's lightning defeat, that message was terribly plausible. It's no wonder The Battle of Dorking was a bestseller. In a world with repeated wars and threats of war, it's no wonder the genre stayed a bestseller even in the United States.

In that, we can see a part of the Victorian mindset which isn't really around anymore.

In their day, war was imaginable and survivable. We remember the Cold War, where the war would have (proverbially if not actually) extinguished all civilization, and the Bomb was (proverbially if not actually) impossible to stop once in the air - but in their day, France was still around after its defeat, and Britain could imagine surviving Dorking too.

And just the same, one could see how France could have stopped the German onslaught with more preparation. One could write about an average volunteer trying to stop the invaders at Dorking, with hopes that he and his regiment could actually do something (if only they'd been better equipped and led), in a way one couldn't write about an aviator trying to stop Soviet bombs.2

What's more, in a world of coequal Great Powers, world-changing wars (like the Franco-Prussian War) actually could change the world. Today in Ukraine, Russia isn't fighting Ukraine - or, at least, it isn't fighting Ukraine alone. Ukraine is backed (to a limited but real extent) by Europe and the United States which will help them mend problems even worse than the fictional British at Dorking. In the 1870's, there was no American superpower and no atomic bomb for anyone to appeal to. A lesser power could appeal to a great power, like Serbia historically did in 1914... but in the last resort, the Great Powers were on their own against peers.

Of course, when Serbia appealed to Russia in 1914, it started a war far longer and far harsher than anyone - even Wells who wrote of Martian invaders - had imagined.

The invasion literature - or the popular mood spurred by it and by smaller wars - had worked. Every army had improved significantly since 1871 and Battle of Dorking. Unfortunately, their foes had improved too. Even more unfortunately, everyone had improved to a point of stalemate that destroyed Europe and left people crying out that surely war should be unthinkable.

Yet more unfortunately, it wasn't unthinkable; soon there would be another war, and then a world-spanning Cold War that (at least in imagination) threatened unstoppable nuclear annihilation.

Invasion literature, like Dorking, War of the Worlds, and Uncle Sam's Boys, offers us a look back at a world sort of like our own, but with a mindset not like our own. It was a world where peace was fragile and was known to be fragile, where war was possible and survivable, where in time of peace one really did have to prepare for war and where one might be mobilized in the army come a turn of world affairs.

That's a mindset that one can find through most of history, because the conditions that produced it can be found through most of history. It's good that, for much of the world, those conditions no longer apply to such an extent. But learning to envision that mindset can stretch one's mind and help one to understand history better.

“Sixth Column” has been called out for racism, and the callouts aren’t incorrect. That said, it didn’t originate with Heinlein - he was working from an outline by editor John W. Campbell, and he significantly toned down the racism from the outline.

I’ve read one story - a chapter of E. E. Smith’s 1948 “Triplanetary” - which does star an air force commander working to stop nuclear bombers. However, it’s a short chapter. For all his skill, the commander goes down to inevitable defeat. To readers of 1948, nuclear bombs were unstoppable.

>Invasion literature isn't focused on plausibility of details. Chesney doesn't name any foreign power, talk about how British logistics got snarled, or explain the invader's logistics.

I'm not sure this is entirely true. The Riddle of the Sands, probably the most prominent invasion novel of the day (at least as far as influence on British military debates goes) apparently does have quite a bit of detail on how Germany might try to invade. (Of course, it wasn't always Germany, with The Great War in England in 1897 being about a French invasion and chronologically between Chesney and Childers.) A lot of this took place against the background of a very vigorous debate in the UK about how best to defend the country, with one faction basically believing that "the invasion will always get through" and would need to be defeated by a standing army. Astonishingly, this faction was usually associated with the Army. The other faction though that the RN would be able to stop invasion. That faction was right, although it is worth pointing out that the whole thing took place against a background of absolutely no experience with amphibious operations against a serious foe. Gallipoli probably did a lot to kill off the genre, as well as the whole "not being invaded in WWI" thing.

It's probably also worth noting that people saw conventional aerial bombing pretty similarly to how we view nuclear weapons in the interwar years, with a fair bit of paralysis and an absence of good stories, at least as I can recall.