Cold Equations, Cold Awakening

It's a good story. The criticism raises good points, but that's another story.

The other week, I happened upon another round of criticism of the famous - or infamous - 1954 sci-fi short story "The Cold Equations".

"The Cold Equations" is a short story that sets up a situation of inexorable physics, and yanks on the reader's feelings while reiterating how it's inexorable. A naive girl traveling on the interstellar liner has stowed away aboard the emergency pod ("EDS") that's detached to deliver medicine to a nearby planet. She's ready to pay a fine for violating the rules - but in fact, her additional mass means the pod won't have enough fuel to brake now. So, she must step out into space to save the pod's pilot and the planet. The pilot, the narration, and she herself all lament her fate at the hands of "the cold equations" of physics.

From that day to this, this story's stuck in fans' heads. Some like it; others are angry about it. Some protest that ethics must not be forgotten in an emergency; that we can't simply nod at the girl's death as inevitable. They protest (as some did on the Reddit thread I saw) that it misses the real story; that the real problem isn't with nature but with the people who built the ship; that we must not focus on the question the story talks about, but instead think about how to build systems so things like this don't happen in the first place. These are good points in their own right, but it isn't a flaw for the story to neglect them.

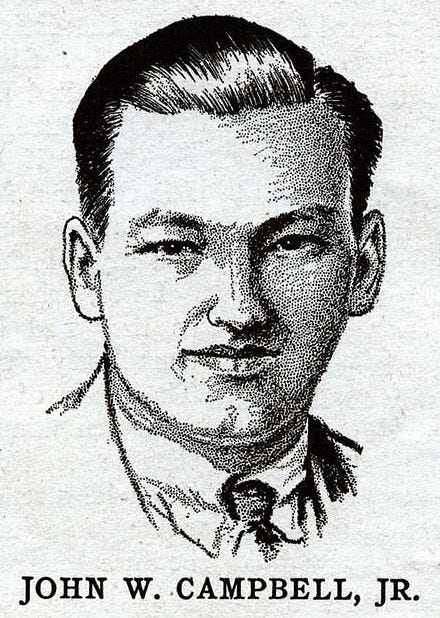

The story is credited to sci-fi author Tom Godwin, but it was essentially written by Astounding magazine editor John Campbell, a prominent figure himself in Golden Age sci-fi. He sent it back to Godwin three times, demanding the girl die in the end. Godwin kept trying to rewrite it so she gets saved by some ingenious scheme, as was typical in Golden Age sci-fi. But, in the end, he gave in to Campbell's insistence. Campbell explained afterwards that he was just motivated by a responsibility to improve a story.

And, yes, it's the ending Campbell insisted on that made this story something I'm still hearing and writing about today.

If Campbell wanted the story to be memorable, he definitely succeeded. It succeeded for the pathos that culminates in the ending, not the plot. But there's very little plot or characterization; from beginning to end, the story focuses on pathos. We're treated to a tour de force of the Naive Girl's naivete, set against inevitable death from the Cold Equations.

Is this a good plot? Not as such. No character attempts anything, save Naive Girl attempting to sneak aboard the ship, a plan that went horribly right. But the point of the story is that, after that, there can be no plot that isn't in vain. The Cold Equations are inevitable. Given that, the most that a story can do is soak in the pathos. The story that emerged from Campbell's edits does that very well.

Is the worldbuilding scientifically plausible? In generalities, yes. Earlier this year, I was reading a lot about aircraft disasters, and there are absolutely points after which it's impossible to save anyone on the aircraft. The safety record of modern aviation comes from decades of identifying every factor that goes into disasters and making those points as remote as possible. There are, in fact, points and places where (as the story's narration puts it) "hard and relentless" laws are needed.

The specifics are also not impossible. There could, in fact, be an Emergency Dispatch Ship (EDS) decelerating with fuel requirements that could not take the extra mass of one young woman. Fans have worked out the math. Her remaining alive and breathing as long as she did in the story tells us there was even some leeway given for extra oxygen. Some critics have protested that the story doesn't show the EDS has minimized mass, which would mean there could have been more leeway in fuel if they had - but perhaps, in a 1950's-vintage world that didn't anticipate computers, things like a pad of paper were indeed taken to be necessary? Perhaps "the boxlike bulk of the drive-control units" (on which Naive Girl sits and presumably writes her letter) was necessary to the drive itself, and perhaps the closet door and blaster were built out of some plastic that was minimal in mass compared to Naive Girl herself?

It feels unlikely to us today, but it is not impossible for the EDS to inevitably land our characters in this situation once they were aboard it. So, once the story has opened, there's no real ethical dilemma left. To save the ship and the planet - to get the medicines to the planet - Naive Girl can't survive.

Some criticisms of the story - such as Ogden's 2021 response story "The Cold Calculations" - have criticized these specifics as implausible. But, they're taking an easy route out rather than engaging with the original story's themes.

That said, when the NTSB is investigating a modern aircraft disaster and finds a point where it would've been impossible to save people, they don't stop there and throw up their hands. They look further, to find why it wasn't caught in time. If it's due to a Naive Girl ignoring a warning sign - or even a trained pilot ignoring procedure - they look at why the sign wasn't clearer and why no one else checked up on things in time.

Writer Cory Doctorow is not precisely correct when he indicts "The Cold Equations" as "a story designed to excuse the ship’s operators... for standardizing on a spaceship with no margin of safety." There is obviously some margin of safety, since Naive Girl didn't doom the EDS with her first breath of oxygen. However, the story does ignore how "the ship's operators... standardiz[ed]" on plans that didn't gracefully catch human error.

But that's now. The story was written in 1954.

In 1954, OSHA didn't exist, and the NTSB hadn't started digging into the root causes of air disasters. If the 1954-vintage NTSB had investigated a disaster like this, they would have just written down "Passenger died due to ignoring warning signs" and gone home. 1954-vintage readers wouldn't have been primed to keep looking for deeper causes. Yes, a story that dug into things like that would have been a good story even then. But, this isn't "a story designed to excuse the ship’s operators" because in 1954 they wouldn't have needed any excuse.

In fact, "The Cold Equations" does move things in that direction. In any other story of its day, someone would've found an ingenious trick at the last minute, and the Naive Girl would've been saved. That happened in Godwin's first drafts! That says a lot of nice things about the power of human ingenuity. But if anything would "excuse the ship's operators", it's that. In the typical Golden Age Story, the ship's operators wouldn't have caused a disaster at all, because some desperate contrivance would've saved everything at the last minute anyway.

Compared to that, having the disaster actually happen wakes people up.

Yes, in a good society, there'd be another part of the story. I'd like to read the story about the Space-NTSB investigation. But that's another story, and one part can be told without the other.

But more importantly than whether a story wakes people up, is whether it's a good story.

"The Cold Equations" is a good story because it's so striking. Godwin's earlier drafts would have been deservedly forgotten along with so much other Golden Age melodrama. When the Naive Girl actually does die in the end - when there isn't some contrivance to save her - when the problem can't be surmounted - then, that story sticks in our heads.

It isn't just the melodrama. It's that our genre expectations are being subverted in a way that - we realize afterwards - has been telegraphed from the start. When Godwin and Campbell are saying it's an impossible situation, we might think they're going to subvert their narrative in the end, but we realize too late they've been playing it straight. That might be tiresome in a longer book, but in a short story like this, it's great.

And on top of that, it invokes questions so deep that we're still discussing them seventy years later.

Oh, good for you. I'm glad to see a critical response to "The Cold Equations" that doesn't miss the point Campbell (more than Godwin) was making in it.

I'm thinking also of Heinlein's story "Sky Lift," where medical supplies need to be taken to a research base on Pluto, and getting them there before it's too late requires constant acceleration at 3.5 gravities, for several days—which turns out to be a tradeoff of the two pilots for a much larger number of other people. To my mind it's one of his best short stories.

I find this fascinating for what it says about genre. I don't know the story and SF is a pretty small part of my reading. But the fact that this story has been so controversial in the genre for so long is really interesting. Basically, it is a lifeboat story, which used to be fairly popular back when passenger ships were a thing. Moving it from the oceans to space doesn't really change much. In some sense, it purifies it, because the lifeboat story had that element of when will we see a ship, which this does not. In that sense it is more akin to the plane crash in the mountains story, which was also popular back when planes crashed in ways that were possible to survive.

But obviously, bringing this familiar trope into the SF genre, even at a time when the lifeboat story and the plane crash story was much more common than it is today, was a big thing. Why should that be? I'm not enough up on the genre to assert this with much confidence, but it seems to me that SF is, or, at least, was, the genre of competence. It was the genre of intellect, in which neither virtue (as in fairy tales), nor courage (as in military stories), nor ruggedness (as in westerns) was the defining virtue, but competence. And here was a story in which competence availed nothing. And as your account of the reaction seems to indicate, the main thrust of the criticism was exactly this, that competence should have prevailed.

This serves, in a small way, to reinforce my impression that genres are defined not by subject matter or location, except incidentally, but by their defining virtues.