Ever since childhood, I've been fascinated with ancient Rome. One of the things I keep coming back to read about is Roman schools. I still haven't dived into them as deeply as I want to, but one thing that fascinated me is how they combined literature classes with general knowledge classes

The Romans had a standard list of classic texts used in schools, including the Iliad and Odyssey and Plato's dialogues and most of the other ancient texts we have. (In fact, most of them survived because they were copied all over the Roman Empire for use in myriads of schools.) Students would take turns reading a short passage from one or another of the texts, and the teacher would then explain it, unpacking each reference and allusion. So, the students didn't just get to learn the story of the Trojan War or Socrates' thoughts on justice or whatever they were reading that day, but also every point of background information referenced by the text - about mythology, history, natural philosophy, and geography.

I was thinking about this the other week, when I realized people do a variant of the same thing today: "wikiwalking." Websites are almost ideal to do this: instead of a teacher explaining who the Myrmidions are and what the significance of the allusion is here, Wikipedia can just hyperlink the word and interested readers can follow it up themselves by reading the other page (or a part of it) before continuing. Actually providing this link piques people's interest by showing the connection. Someone might've never thought of the Myrmidions before seeing them mentioned in the article or poem, or might've glossed over the mention without seeing the link there, but the mention and link will give a connection that often does prompt people to click and learn more.

(This was in fact one of the original use cases for hypertext.)

Even without hypertext, I'd sort of done the same thing myself in my childhood.

As I've mentioned, when I was a kid, I read a lot - including kids' books, but also some adult books. One of my favorites, which I read and reread, was an old 1974 hardback The Kings and Queens of England: A Tourist Guide by Jane Murray. It describes briefly the reign of each English monarch from Elizabeth II (1952-then-present) back to Edward the Confessor (1042-1066). I say "describes briefly" because there're tons of allusions to things Murray assumes the audience already knows, whether Labour government and decolonization under Elizabeth II or "'Fair Rosamund' of the legendary house in the maze" under Henry II. That's the exact wording; neither house nor maze are explained further.

I didn't understand a lot of these references when I first read the book, but I remember loving their depth. And also, a lot of them did give enough context for me to understand - such as the summary descriptions of various kings' wars and social conflicts inside the royal family. Edward I's crusading, Edward II's struggles with the Marcher Barons, and so much more gave me a brief overview of English history, sort of like I would get from reading one summary article. Just like reading the initial wiki page piques someone's interest in clicking a link, this book piqued my interest in English history. Later on, I could - and did - fill it out with more detailed books, as if I was wikiwalking over a period of years.

I think I did the same thing with twentieth-century American culture thanks to writers like the humorist Erma Bombeck, who wrote humorously exaggerated portrayals of American suburban life. A lot of the jokes and references went over my head, but I liked it anyway and wanted to learn more.

Despite my ignorance and the inability to actually click hyperlinks or ask a tutor (sometimes I did ask my parents), at least I learned at least that there were issues there behind her exaggeration. Actual wikiwalking wasn't around yet; Wikipedia was only just starting to exist, and I didn't yet know about it. But I was trying to approach it here.

From this, I can recognize what the Roman schools were doing: by giving children all these allusions and explaining them, they were giving them both historical and cultural background knowledge. They were giving them common reference points and raw material for what they'd be doing later in life. This was "a liberal education": etymologically, an education fit for free (“libertas”) citizens who'd be helping run the nation and thus would need to know these things.

My reading wasn't quite the same thing as either the Roman education system or actual wikiwalking, because I was doing it by myself without a teacher or hyperlink, which meant I was picking up awareness without someone or some other webpage to explain the references at length. But there're substantial similarities. When I did eventually get Internet access and start spending a lot of time on places like Wikipedia, I recognized the impulse for wikiwalking as the same impulse that'd led me to read and reread The Kings and Queens of England and eventually dig into what it alluded to.

But what was more, early imperial Rome had a generally standard set of texts which let teachers and students wikiwalk through their culture. Perhaps there were a few teachers who preferred the Cypria (a Greek epic poem now lost) over the Odyssey (which most preferred, which's why we still have it today), but pretty much everyone was working from Greek epic poems set in the same heroic era and using the same general allusions. When statesmen were debating the issues of the day, they had the same allusions in mind. When people were addressing educated audiences, they could allude to these poems and their background information knowing that people would recognize them.

America still has this to some smaller degree. Internet memes reference TV shows or games, and editorials can allude to a small set of texts such as Harry Potter or Lord of the Rings or (at least for a while) Hunger Games. One youth pastor I know says that Harry Potter is the one thing he can count on every single teenager knowing about. But even there, editorials are forced to explain the allusions. They can't assume everyone has read those texts.

At one point, speakers and writers did assume most of their audience could get allusions like those. In his 1856 "Crime Against Kansas" speech (against the fraudulent pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution), Senator Sumner could not just make an extended analogy to "Don Quixote and Sancho Panza" but name-drop "an audacity beyond that of Verres, a subtlety beyond that of Machiavel, a meanness beyond that of Bacon, and an ability beyond that of Hastings" - all without explanation.

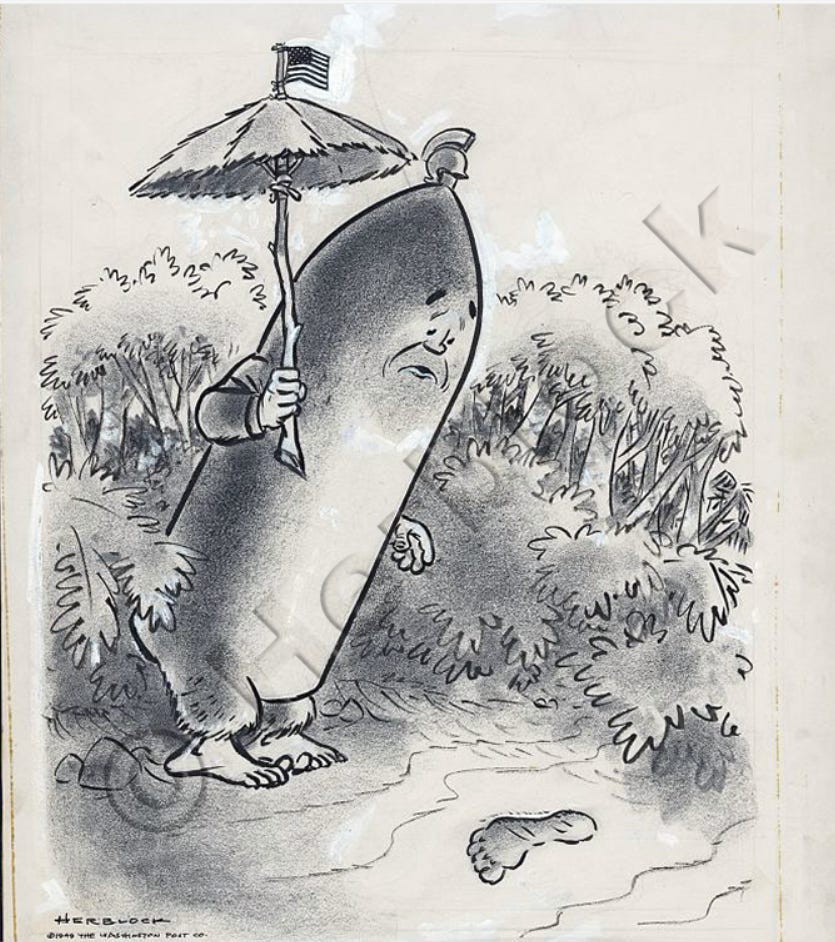

Even as late as 1949, Readers' Digest could publish a political cartoon about the new Soviet atomic bomb, confident that their readers could not just recognize but interpret the detailed reference to Robinson Crusoe:

After living alone on his island for years, with no possibility of rescue in sight, Crusoe unexpectedly comes across a footprint. He's shocked and discomfited. Another human is nearby. Could they be hostile? He flees back to his hut in fear. The cartoonist analogizes the sudden sighting of a foreign atomic bomb to that - in a way assuming that almost all his readers would be that familiar with Robinson Crusoe.

In Rome, and in 1856 and 1949 America, people could make detailed references like that. In the modern day - well, I feel I need to explain the allusion with a summary of the chapter. Something has been lost.

But, something has been gained in the modern day, too.

Put most simply, just about everyone can get to Wikipedia. In Rome, only the upper classes got to go to these schools and get the "liberal education" intended for free citizens. Now, just about everyone in the First World is a free citizen who can take some small share in running their nation. We may not have as good a wikiwalking education as the Roman upper classes, but a lot more of us can and do wikiwalk.

And what's more, the Internet gives us lots of knowledge on all sorts of subjects - even those that didn't get into the Greek Epic Cycle. In Greece and Rome, the "liberal education" didn't cover technology or economics or many other things. Greece and Rome suffered for that. Roman economics suffered from a lack of attention (as Edward Salmon describes in his The Making of Roman Italy): educated Romans didn't know or care for economics. The modern First World has taken a different course, and prospered greatly.

As a perhaps-unwittingly-profound politician put it, even worse than not knowing something is not knowing what you don't know. Having a short answer for a number of questions isn't as good as actually knowing about them, but it can give you a valuable start.

Wikiwalking isn't just a new thing. It builds on something that was around for a while - in organized Roman schools, and I'm sure to some real extent before then as well. It fits how humans learn, and it fits how human societies are built around shared stories and canons of knowledge. The Internet hasn't created wikiwalking, but just given it a name.

But the Internet has also put the direction of the wikiwalk in the hands of every individual learner. To some extent, Rome's common corpus of knowledge was because of the limits of its learning. If one student would rather study the Cypria, or some other tale we don't even know the name of, that didn't matter because his teacher had a small set of texts and a small capacity for explanation. Now, the Internet lets everyone wikiwalk in their own directions.

Perhaps it's inevitable this would end the idea of a common corpus. I'm sorry to see it go. But, the concept of wikiwalking is still here, and now even more widespread than before.

It's also interesting that encyclopedias (basically manual hyperlinks) as we know them originate around the beginning of the Roman Empire.