Tuning the Morals and Economy of the Shire

Jumping off from Nathan Goldwag's post on "The Moral Economy of the Shire"

There was recently a really good blog post on "The Moral Economy of the Shire", viewing hobbit society in Tolkien's Lord of the Rings in the light of real history. The blogger, Nathan Goldwag, maps out a plausible picture of political and economic life among hobbits in the Shire. I liked his article a lot, and I do recommend it; it's a good analysis of premodern history, and mostly a good interpretation of Tolkien's worldbuilding.

In short, Nathan says Tolkien's worldbuilding of hobbit society feels like something that could happen, and resembles some real premodern societies - if things aren't as prosperous as they seem, and if upper-class hobbits like Bilbo have a lot more coercive influence over their neighbors than we see on the page. I'd like to pass over several of his very interesting arguments, and talk about two of the major points he made. There's a lot I could say about them from the historical angle, but I'd like to instead talk about how the picture of the Shire Nathan gives us here relates to the picture we see from Tolkien.

One of Tolkien's great strengths is that his world holds together enough that we can write articles and debates like this about it. One reason for this is that he spent almost all his life on it, from scribbling poetry while recovering from World War I wounds in 1916 to trying to rebuild Galadriel's backstory the week before his death in 1973. His world has rich details because he took the time to build them in.

But the other reason we can dig into it like this is - as Nathan says - because Tolkien was familiar with history. Some of it, he'd lived through himself; most of it, he'd studied throughout his academic life as a professor of Anglo-Saxon language and literature. This means that he didn't need to come up with every idea himself, or think through all the implications himself. Rather, he could pull in real-life concepts and cultures, confident they could hold together because something very like them did hold together in real life.

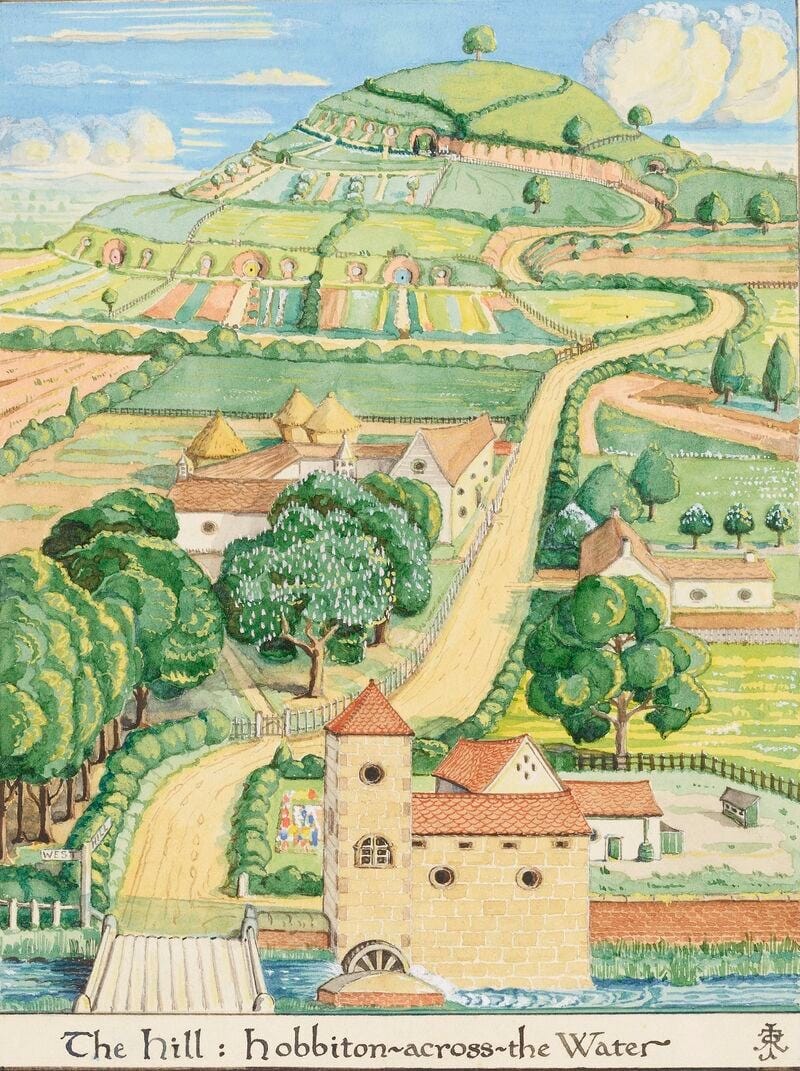

Tolkien doesn't show us these worldbuilding details. He just shows us a bucolic prosperous Shire with no visible organization until a Thain and Mayor and Sheriffs are mentioned at the very end of the book amid the Scouring of the Shire. That works, because that's all that's needed for the story. What he shows gives us the right impression of the Shire for us to appreciate the story.

Even the brief explanation of who the Thain and Mayor are - how "As mayor almost his only duty was to preside at banquets... [but also] he managed both the Messenger Service and the Watch" - goes into the Prologue. Similarly elsewhere in the tale, a lot of the history of Gondor found in Appendix A was originally spoken by Faramir in the text, but moved when Tolkien thought better. Not all the details need to go in the story.

Nathan, in his blog post, expands on this with historical analogies.

As Nathan says, the gentry system of the Shire is inspired by the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English "squirearchy." Tolkien says the Shire had almost no official government - similarly, nineteenth-century English country squires (such as the protagonists of Jane Austen's novels) had no official government titles. Tolkien also says "the Shire at this time had hardly any 'government'. Families for the most part managed their own affairs" - from which Nathan concludes that the Shire is plausibly "a society organized around family and clan dynamics" and "patron-client relationships" mediated among other things through gift-giving.

He's right about the analogy to nineteenth-century England. The life described is much more similar to there than anything earlier - the Green Dragon inn, the regular postal system, the catering at Bilbo's party, the dialect, and (as Tolkien said in letters) the characterization of the Hobbits themselves. England did have a government then, but in many parts of the countryside the squires were much more present than the government.

But nineteenth-century England was not, in fact, the isolated provincial society we see the Hobbits to be. It was at the core of a growing global empire and global trade network, which provided many of the resources and luxuries (from timber to tea, and more) that made England so prosperous. The prosperity of England was largely due to that.

Yes, many English people were as provincial as Tolkien's hobbits (especially in the remote countryside), but many others weren't (especially near the coasts and large cities.) When Tolkien first wrote about hobbits - in The Hobbit - his description was vague enough that it was possible they could've had similar trade networks. But in Lord of the Rings, they clearly don't.

What's more, even if the Shire had wanted to have that trade network, it couldn't in Middle-Earth. The rest of Middle-Earth is, by Earth development standards, a millennium or more before the nineteenth century. England couldn't have maintained nineteenth-century prosperity without the rest of the nineteenth-century world; they just wouldn't have had enough to trade.

As Nathan points out, transplanting rural England without the trade network leads to economic difficulties.

In his blog post, he constructs a different model for the Shire's economy. He ignores nineteenth-century England, looks to very different models, and bases it on gift relationships and clientage. This works, in that it hangs together; it feels like a place that could exist. What's more, various lines in the text can easily be taken to hint in this direction. What's more, a lot of it does feel like the Shire we read about.

But, it can threaten to lead to character problems.

Nathan observes that premodern agriculture wasn't actually as fruitful as we see in the Shire. In the Middle Ages before modern transportation and long-distance trade - which is what we see in Middle-Earth - it was even less so because of the constant need to guard against one very bad harvest causing famine. Nathan argues that we see prosperity and abundant food in the Shire just because our protagonists are in the upper class.

In the real world, medieval peasants were regularly facing hard times and verging on starvation. The nobility got their luxuries by, sometimes literally, taking food from starving peasants. (This's one reason why the medieval Church often called out luxurious living as a sin.) Nathan points out that, according to these historical precedents, Bilbo and Frodo are in the place of these medieval nobles. They don't have formal titles, but they are filling a similar economic role, and a somewhat-similar social role.

Tolkien doesn't show us this, and - what's more - it doesn't feel right. It conflicts with their characters that he does show us. We don't, and can't, see any of the Hobbits we know doing this. When Saruman's men did something like this, even the villainous Lobelia Sackville-Baggins herself protested and got thrown in the Lockholes for her pains.

Nathan mostly passes over this. He only mentions that "the relative 'looseness' of the system" can be explained by how "from everything we’re told, the Shire is a very agriculturally productive region." He's right. What's more, that would help keep things in character: Bilbo and Frodo can have their luxuries without Gaffer Gamgee or anyone else half-starving. In fact, if second (or first!) breakfasts exist beyond Frodo's social class, the Shire would have to be more productive than most premodern places on Earth!

Potatoes might be one part of this. They're more nutritious and calorie-dense than anything grown in actual medieval Europe, which is why they became so popular once introduced. Of course, in the real world, they also caused a population boom we don't see in the Shire.

But another part is that Tolkien didn't bother making his botany realistic. He loves talking about forests in detail, but the background is less plausible. For example, Dwarves built whole underground cities - what did they eat? There's no room for farms on the mountains above Moria, and those dwarves couldn't have depended on food from Hollin or Lorien next door (even absent racial tensions) because we know they endured sieges, and they canonically lived there before the Elves came! Perhaps they all ate mushrooms... but that would require either mushrooms we don't have in the real world, or metabolisms different from humans', and we don't hear about any Dwarven mushrooms. What's worse, we read in Silmarillion that forests grew, and Elves lived there, before the Sun existed.

I, as a Tolkien fan, conclude from this that crop growth in Middle-Earth is just different from crops on actual Earth. Perhaps they have varieties of plants we don't have; perhaps the soil has some magic in it. Both of these could be vaguely implied in the text: we know lembas-corn and Kingsfoil exist, and we know that Kingsfoil only grows around the sites of Dunedain camps. This means the Shire can have whatever level of agricultural prosperity makes its economy hang together without doing violence to the characters.

Was Tolkien thinking about anything like this when he designed the Shire? Probably not, beyond making it echo rural England. The only place he directly analogizes it to in his letters is nineteenth-century England, but there're some points in the text which echo earlier eras of English history.

But, that in itself brings on much of the analogies Nathan talks about - because English society itself resembled, and descended from, societies like this. That's the richness of history: history is fractally deep, and has more connections than any one person can bring to mind. Modeling your story off real history brings with it some of that richness.

And that makes it more fun for the readers to analyze.

A gentle suggestion: I have not worked out the math, and there may be textual evidence against it that I don't recall, BUT... Hobbits are very small. Presumably, then, their daily caloric needs are much lower. Land that would only provide bare subsistence to a family of Men might, then, provide five hearty meals per day to a family of hobbits. This could help explain the Shire's apparent productivity without having to advert to Middle-Earth's different biology & physics.

I wrote about this topic back in the 20th century, in "Law and Institutions in the Shire" available through the Mythlore web site at https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol18/iss4/1/ . I saw early Iceland as one of the prototypes for the Shire, though I hadn't read as much about Iceland then as I have since.