Picture, late in the night of March 3rd, at the US Capitol, in 1815 or 1817 or thereabouts. The House of Representatives is meeting, working hard to rush through the next year's budget and other important laws before their terms of office expire at midnight.

It doesn't look like they'll do it. There're too many bills to go, and too many Congressmen debating them, and midnight is too close.

But then - the Speaker nods to the clerk, and the clerk walks over and sets back the clock. It was reading maybe 11:55 PM; now it's reading maybe 8:55.

They've given themselves more time to debate by changing time. March 3rd, and their terms of office, will last another few hours.

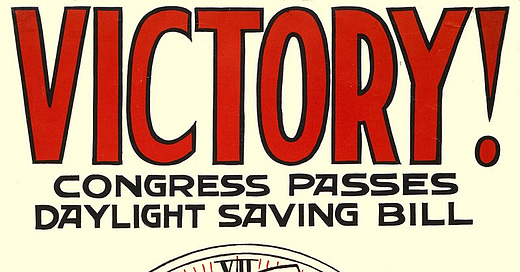

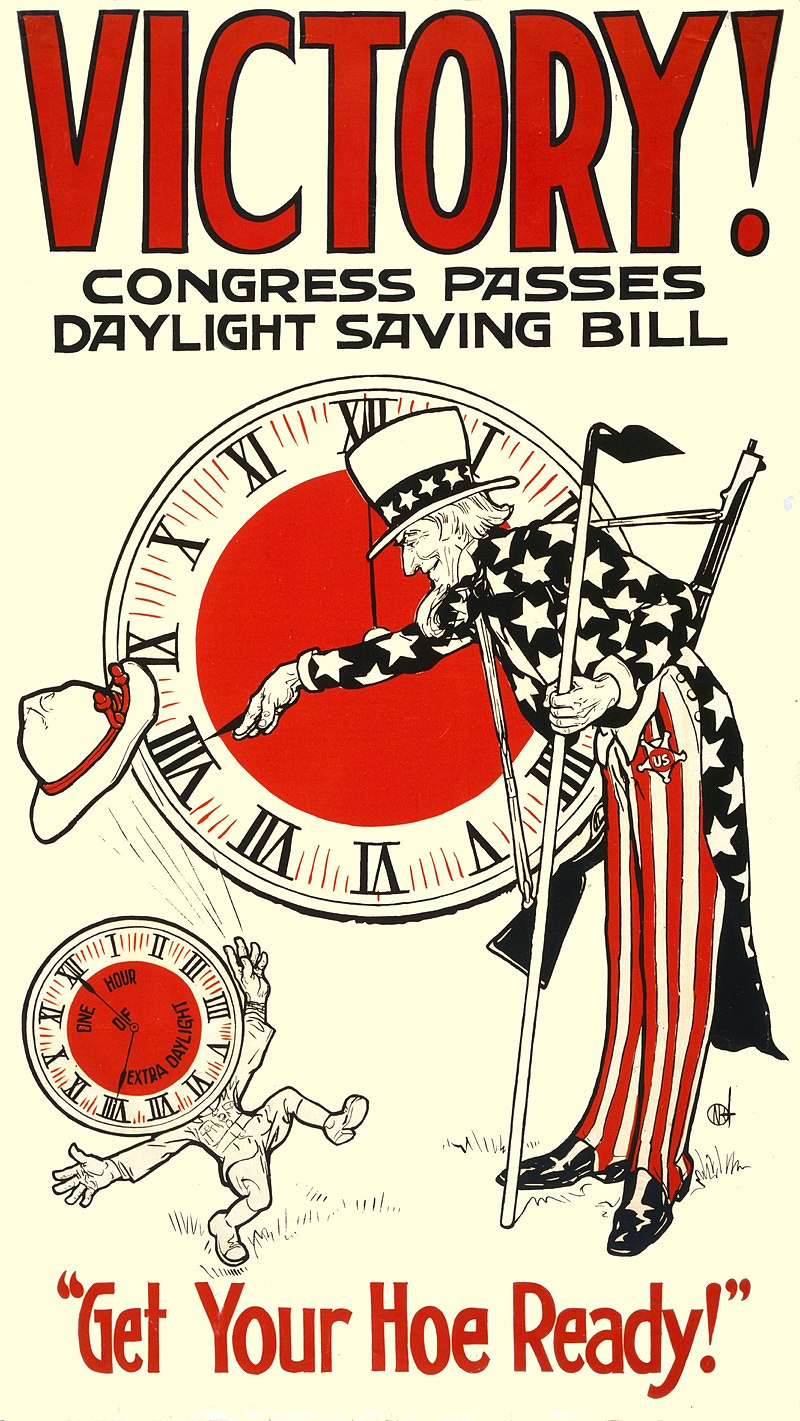

Tonight, in most of the United States, Daylight Savings time starts. We set our clocks an hour ahead, and leave them there until next November. Until November, the time shown on clocks will be different from the time shown by sun and stars. We're so far removed from nature that we barely notice how we ease things for society by manipulating the abstraction of time.

Thus, we strain the link between the clock and the sun, changing the meaning of "noon" to ease the coordination of society. "Noon" used to mean the sun was at its highest point, and we used to measure time from there. Yet, triumphantly, each summer, we throw off the shackles of nature and change the meaning of words because we want to.

Or, that's one story to tell.

It's not a wrong story; it's one simple way to view things. But there're other narratives that can be made about the situation. We've already thrown off the shackles of nature in our timetelling in other ways, which we usually don't think of.

When the clocks in Washington DC read noon (on standard time), it's actually about eight minutes after noon by the sun. This's because we've divided the earth into time zones; Washington DC is at 77 degrees west, but it's in the US-Eastern time zone, and that entire zone sets its time as if it was exactly on the 75th meridian west.

Originally, each town set its clock from the sun every day. By definition, noon in that town was when the sun was "at the meridian", or the highest it would be that day. This meant that time in each town would be slightly different from time in towns to its east or west. But, when the fastest way to travel was by horseback, that didn't really matter. Travelers couldn't keep clocks accurate while on the road, and traveling took long enough that, by the time they got there, they couldn't even tell the difference.

What changed this was railroads. For the first time, people could travel fast enough that the time difference mattered. By 1840, the Great Western Railway in England had already started using one unified time for all stations on all its timetables - effectively, creating one time zone for itself. Other railroads would quickly follow.

By 1848 in England, all railroad guides were using the same time: Greenwich time, defined by the sun at the location of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. American railroads (with less government coordination and a much broader area) took until 1883 to establish unified time zones. At first this was just the train stations, but soon the rest of the cities followed them. In 1884, the International Meridian Conference agreed on the Prime Meridian, which didn't technically require standard time zones but pushed countries toward them.

So, henceforth, noon no longer meant solar noon. Time on the clocks was decoupled from the sun. Places had to either pick a time zone or make their own, but time was now not solar but zonal.

This made the world a much easier place to travel and do long-distance business, which was increasingly important in the globalizing world. There was a good reason to unlink ourselves from the sun to this limited degree. But, that was still what we were doing.

But this's nowhere near the most elaborate game we humans have thrown up against time.

One of my favorite tales of sheer temporal impudence is the Roman Republican calendar. They didn't have a leap day; they had a leap month, added every several years at the announcement of the chief priest. Supposedly, he would give his announcement after studying the stars and the seasons to keep the calendar in sync with the solar year.

In practice, the priest would regularly put in an extra leap month to keep his political allies in office longer, or delay it to get his political enemies out of office sooner! Things were so irregular that modern historians can often only guess at what month Roman Republican dates should've been in. I've read one book that spends substantial time trying to figure out whether particular dates were in fall or winter, because of the calendar confusion.

It was Julius Caesar who eventually ended this confusion. After he became Dictator of Rome, he established the Julian Calendar, which had one fixed leap day every four years. That's so good it only needed one small reform between then and today. Our modern Gregorian Calendar keeps that, except that (due to better calculations of the year) three leap days are dropped every four hundred years.

But Julius Caesar didn't end politicians changing dates and times. It cropped back up in the early United States.

When the United States Constitution was adopted, it didn't specify exactly when terms of office would start or end - just, that (for example) the President "shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years". The new government decided to follow that exactly. Congress had first met on March 4, 1789 (though, lacking a quorum, it wasn't able to do anything for several weeks afterwards); so all succeeding Congressional and Presidential terms would end on March 4th. To be precise, they were held to end at the stroke of midnight starting March 4th.

But (as this wild law review article digs into), Congress frequently left important legislation till the last minute. By 1816, the House of Representatives was frequently solving the problem with the scene I painted at top. Late on March 3rd, they'd give themselves more time by literally setting their clock back. Their terms would end at midnight... but they were redefining midnight for themselves.

In 1835, and again in 1849, Congress decided to turn over a new leaf: continue sitting after midnight without bothering to set back the clock, letting the clock pass midnight, declaring that the "legislative day" of March 3rd stretched until 11 AM or noon on the 4th. All legislation passed after midnight would still bear the date of the 3rd. As Senator Jefferson Davis (D-MS) put it, "The political day, as it has been fixed is conventional and therefore we have a right to call upon this body to put their construction upon it."

There were objections and even pandemonium around midnight. Representative John Quincy Adams (Whig-MA) cried "If the assertion that the House is not in existence is true, then no motion can be made"; Senator Henry Foote (D-MS) claimed "we have no right to sit here... this body is no longer in existence." But it happened anyway. Lame-duck President Polk in 1849 claimed to be dubious about this, but did sign legislation after midnight to prevent "vast public inconvenience".

In 1909, Congress became even more brazen, dating legislation as March 4th.

All this was mooted by the Twentieth Amendment. The Amendment was mainly written to move Inauguration Day up from March to January, to shorten lame-duck periods. But, in passing, it specified that the terms of President and Congress would end at noon.

So, it isn't wrong that Daylight Savings Time is changing the meaning of "noon" for society's sake, or even politics' sake.

It's just that it's happened before.

From manipulation of calendars for political gain through the establishment of time zones, from Julius Caesar through the US Congress, we've treated time as a construct and a tool that we can stretch and mold to fit the purposes we have for it. Daylight Savings Time is another chapter in that long history.

It can be good, or it can be bad, but each new change is a reminder that our relationship with time is a changing one, a story in itself. And, it's a symbol of our triumph over tradition and nature.