The Vivid and Swift Story of Westmark

How do you keep a good story short?

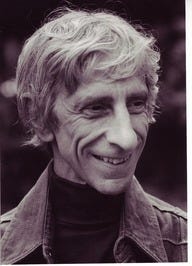

I recently reread Lloyd Alexander’s excellent Westmark trilogy - three short novels, packed full of enough plot to fill a more modern very lengthy trilogy.

This isn’t quite a kids’ series - it dates back to the 80’s, before the Middle-Grade subgenre, but I’m sure it would be classed as that today - but its shortness reminds me of the mid-century kids’ books I enjoyed in my own childhood. Like those, Lloyd Alexander briefly sketches just enough scenes to give us the skeleton of what’s happening and just enough flesh for flavor. We know the story; we feel just enough to feel we’re in it - but an entire winter in the hard hills, or a blossoming friendship, can be passed over in just a couple scenes.

And there’s a reason for that: to make the events in the series readable for middle-grade kids, and tolerable for their parents. Lloyd Alexander does that excellently, too.

And that makes me think, and shows me something of the nature of story.

The first book of the series, Westmark, starts out as a typical kids’ tale. We have our young heroes and their colorful sidekicks, in a fictional kingdom suffering from the tyrannical rule of the evil chancellor who’s misleading the king. They’re drawn into the problem, and must fight him to find the lost princess and save the kingdom.

But, things quickly get deeper. It’s the Age of Revolution. Romantic revolutionaries who seem to be lifted right out of the pages of Les Miserables are there, eager to fight the chancellor too but determined to follow their own cause. Our young protagonist Theo falls in with them for a time and truly looks up to their leader Florian. They raise the question none of our protagonists can fully answer: is the kingship really worth saving? Between this, and the beautiful psychological realism at brief moments (say, when Theo first sees someone killed in battle) this’s a surprisingly deep story.

And then it gets even deeper in the next book, when the grateful king sends Theo on a tour of the kingdom that turns into war. We’re told (with few but vivid details) of the nobles’ misrule, and Theo (and the restored princess who’s reading his mail) realize that the revolutionaries do have a just cause.

But then an invasion leads to a bitter war, with the revolutionaries joining the war, and our protagonists almost losing themselves to rage and hunger and theft. Victory is won, but only through a beautiful character-focused twist, and the princess who now opposes the monarchy is come to the throne.

Yet in Book Three, a coup leads to another invasion, and Theo and the princess are forced to lead a guerilla war in the city while Theo is trying not to lose himself to the violence as he did before. With a beautiful climax and denouement, our characters have attempted to answer the questions raised repeatedly throughout the saga - but they aren’t answers that fully satisfy them, or us the readers.

As the New York Times book review put it when Westmark first came out, “Lloyd Alexander does not answer questions; he raises them.” That’s quite true. His characters reach solutions in the books, but they’re not satisfied themselves; and I the reader am not satisfied either. Threads remain loose throughout the trilogy. Wikipedia calls this one of Alexander’s darker works, and this’s one big reason why. Huge questions are explored - such as how to possibly fight without losing one’s virtue, or how to take apart unjust establishments - but the answers we get still have problems. And let’s not forget how many characters end up dying with relationships still raw, such as the old king in Book Two, or Justin in Book Three whose death still tugs on my heartstrings. He writes here with “uncompromising honesty”, as Jacobs and Tunnell put it in their biography of Lloyd Alexander.

Those questions could fill a lengthy adult dark fantasy. But Lloyd Alexander wrote this for kids. When it first came out, it won the “National Book Award for Children’s Books.” It’s readable by all ages; my sister and I first read it as teenagers and loved it, and I loved it again when I reread it now as an adult.

Alexander does this thorough his brevity. When our protagonist Theo is among the guerillas in the mountains in Book Two, he starts the winter with a raw conscience, shrinking back from any brutality against the enemy or any thefts from local farms. He ends the winter as a savage feared commander called “The Kestrel.” But we don’t wallow in this moral descent. We see just enough: we see one instance of early brutality and theft with Theo shrinking back from them; then we see him reluctantly taking the first steps to join in; then we hear in summary form about his reputation; then we see him realizing in the end what he’s done and coming back to himself. We see just enough to know what’s happening, and know it’s bad, and see where Theo’s character is going. Readers can fill in the gaps themselves, more or less vividly based on their background knowledge.

Nothing here would be out of kids’ possible imagination - they’ve presumably seen bullies hitting people; they’ve presumably seen kids stealing things from other kids. War is clearly shown as bad, and we see enough to see something of how it’s so bad. We adults can fill in more - but it’s communicated well enough for the story.

This’s just one example of many; Lloyd Alexander keeps it up repeatedly through the trilogy. He excellently writes a story with mature themes in a way suitable for children, without dumbing anything down.

Even as a teenager when I first read the book, I didn’t feel anything was missing here in the quick telling.

I posted a while back about rereading some kids’ books I enjoyed in my childhood and realizing how short they were and how it feels like so much more happens than actually happens on the page. Here in Westmark, just like there, the author is alluding to so much happening, giving us a few vivid examples, and stating things keep happening in the same way. I didn’t notice those as a kid, and on rereading as an adult, I was actually surprised to see so little was on the page. Lloyd Alexander was writing Westmark in the early 80’s, slightly after many of the kids’ books I was thinking of, and he’s writing with much more mature themes, but he’s clearly writing in the same tradition.

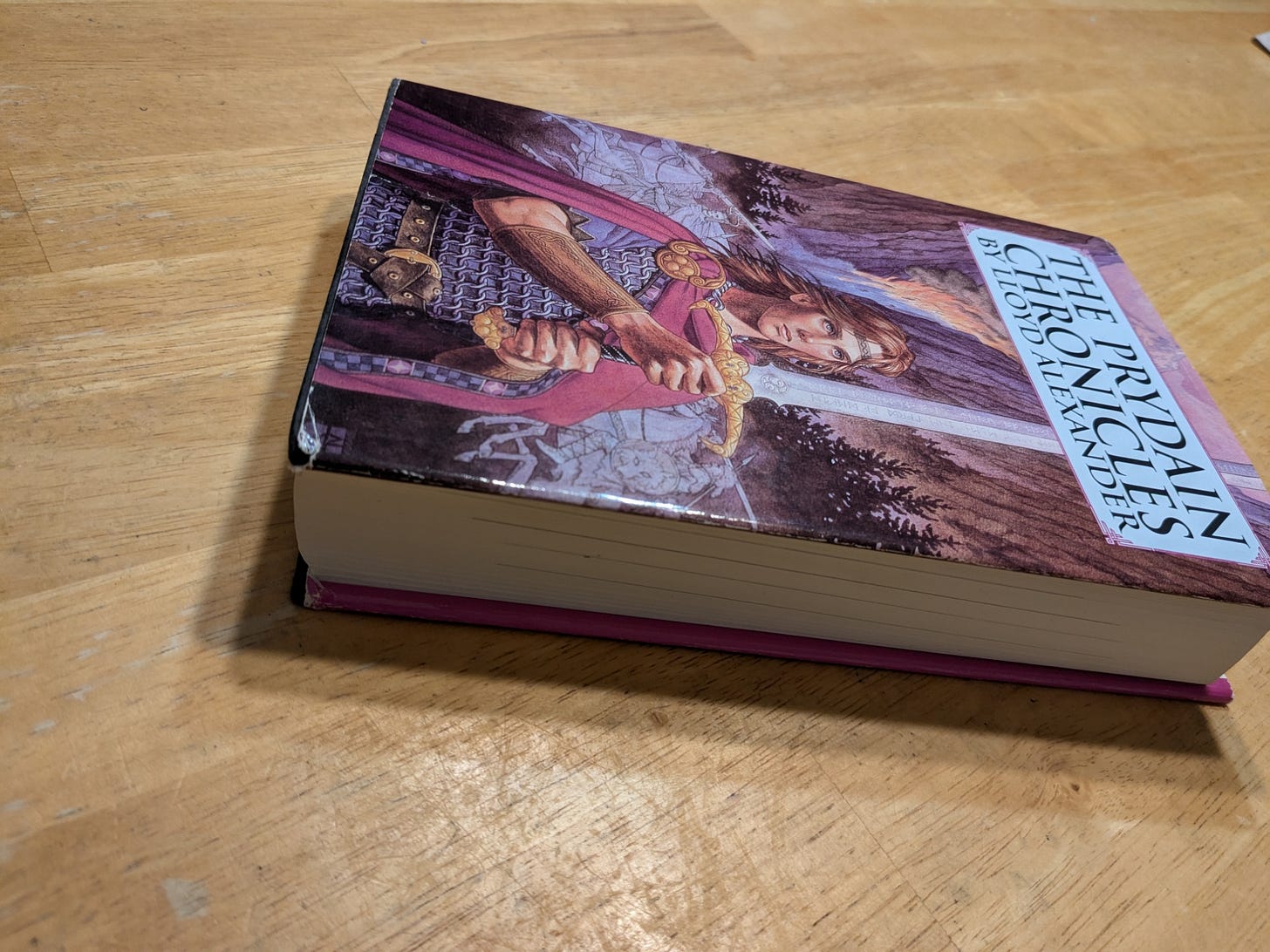

It isn’t just Westmark either. When I was talking with my sister about how short these books are, she reminded me of Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles. In the omnibus I have, they come out to 765 pages... but that includes five whole novels and a short story collection. More modern authors, where one novel can cover 765 pages, could stand to learn from Lloyd Alexander.

True, this brevity leaves a lot of characters with dimensions only gestured toward, a lot of blank spots in the world, and more. Where did Florian’s revolutionary philosophy come from? What actually happens with Las Bombas’ growing moral compass? Or in Prydain, what kept the Free Commots free from nobility, and how did the characters we know there view the rest of Prydain? We can only guess. A longer book might tell us this, as well as more dynamic arcs about the characters’ relationships with each other. That’s a disadvantage of Lloyd Alexander’s short style.

But there’re advantages too. The core plot is told, with a pace that keeps it vivid in our minds without digressions. Or, rather, we get just enough digressions to show different arcs, and a few subplots - like the arc of Skeit the assassin, or the longer arc with Keller the journalist - which serve simultaneously as gestures to build out the world. And, it can be written and read much more quickly, with our imagination filling in the gaps perhaps more solidly or vividly than Alexander’s own prose.

When I’ve tried to write stories - especially novels - I frequently face blank spots in my outline which my sister and I both refer to as “Things Of This Sort.” In other words, I know that there’s some period in which a certain sort of things should happen, but I don’t know what precisely to write there.

Westmark shows me a new way out of that problem. Sometimes, the “Things of This Sort” don’t need to be filled in; they can be just left as gestures toward “things of this sort.” It isn’t just in kids’ books (though Westmark is technically written as what would be called middle-grade); it can be done in books that raise solid questions and confront mature themes too.

But not all questions need to be answered. Lloyd Alexander leaves so many open - painfully open, but any solution would have almost certainly meant rigging the thought experiment with a solution that wouldn’t really solve the question. I’m sure Alexander didn’t have any solution in mind either - he served in World War II combat intelligence, so he knew something of the complexity and bitterness of war. The themes there keep showing up throughout his work, though Westmark is the best exploration of the particular aspects it shows.

Not only is Westmark a good story; it’s a sort of short, fast-paced story we don’t see much of today. It invites the reader to fill in gaps, and that’s one of its strengths - not just in how it can be read at any age, but in how it can build out a world with just a few gestures.

More writers should learn from it.

I didn't realize there were three of these, but the first is amazing!

Thanks for reminding me of this series. I know I was aware of it when I was much younger, but I had entirely forgotten about it. I'll have to pick it up!