The Extravagant Details of Biography

I've learned to be wary of biographies.

All too often, when I find a biography of an interesting person, I start it only to find myself landed in a childhood that, however unique, doesn't have anything to do with what motivated me to read the book. And then, if I'm still reading after the childhood, I'm left in a young adulthood that also only has a few clues to whet my by-now-starving motivation. Chronologically, of course, this makes sense. As a way of sympathizing with the person I'm reading about and understanding their motivations, of course, this also makes sense. But still, something's missing here. After all, if any novel started with several chapters of our protagonist's childhood long before the main plot started, we'd drop it.

But I recently remembered one biography that avoids this.

When I visited my parents recently, I picked up and reread my old copy of Reilly of the White House, the autobiography of the Chief of the White House Secret Service detail under President Roosevelt during World War Two. In addition to being a good book in its own right, it's a good window into the era, and it shows that it's possible to get around this problem.

The book opens with the attack on Pearl Harbor. More precisely, it opens with Reilly (and everyone else at the White House) hearing of it and immediately taking more steps to guard the President against any Nazi assassins. This's an opening that responds to what readers are reading the book for: we aren't reading to hear about Michael Reilly the individual, but about President Roosevelt and the White House. We're using Reilly as a window into his era and his surroundings. And, perhaps thanks to his Secret Service training that he shouldn't be the center of attention, Reilly accommodates this very well.

By itself, that opening could've been like the preface in a number of modern fantasy books, or even the opening scene to Star Wars: A New Hope: one or two scenes of exciting maneuvering and battles before we switch to the protagonist in his as-yet-quiet life. And, indeed, Reilly the author jumps back in time after that scene. Yet, he only jumps back to his decision to drop out of law school and join the Secret Service. Then he goes forward from there, quickly moving to his posting to the White House - we never see any of his childhood, and very little of his life outside the White House. What we get is lots of interesting stories, charming anecdotes, and fascinating details about the job of keeping President Roosevelt safe before and during the war - both in the White House and while traveling.

In addition to this perspective on historical events, we also get a window into a surprisingly different era. For example, in the present day, I recently visited the District of Columbia and saw the guarded security fence almost a block out from the White House. Then, Reilly describes how he needed to lobby to close West and East Executive Avenues so people couldn't drive right under the White House windows and potentially explode truck bombs fifteen feet from the President's study. I can't blame Reilly for the changes. It was in vogue at the time; there were paranoid proposals to even rechannel the Anacostia River lest German bombers use it as a landmark to find the Capitol or White House. What he does is show us an era where that paranoia wasn't yet institutionalized: when he needed to scrabble to find a single partially-armored car for the President; when international travel was such in its infancy that Reilly himself needed to run around four continents scrabbling together ad-hoc arrangements for Roosevelt's travels to Casablanca and Teheran and Yalta.

I'm not holding this up as the sole model for all biographies. It's the most engaging to the casual reader, but there're other things a biography can be going for too. For one example, take Jane Ridley's The Heir Apparent: A Life of Edward VII. Ridley, granted unprecedented access to the royal family's archives, decided to write the definitive and most comprehensive biography of Edward VII yet. I haven't read enough other biographies of Edward VII to say for sure, but I expect she succeeded. At least, we have amazingly detailed and well-sourced chapters on his birth, his childhood, his education, his traveling Western Europe as a dissolute playboy, and every other chapter of his life. Frankly, as a casual reader, I skipped over most of the dissolute travels. If I hadn't been interested in the Victorian era in its own right, I probably would've skipped a lot of the details on his childhood too.

But, scholars interested in extensive studies of Edward VII's life would love all those details. If I'd been (say) trying to trace the origin of some psychological trait of his, or (say) trying to curate the Osborne House museum, an extensive study of his childhood and education would've been just what I needed. Or, someone trying to write a musical with Alexander Hamilton as a protagonist is going to want a good detailed biography of Hamilton. Or from another angle, I read a joint biography of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien last year, and I loved even the chapters about their early lives because I was interested in them and wanted to know all those details.

All these reactions are very valid, because all these details are part of the broader story of history. Just as we might critique a novel for lingering too long on one sequence or subplot, we might say that a history book goes too much into detail. But just as someone else might object that they loved that sequence and it should've been longer, it's entirely valid to go into all that historical detail. One thing that makes the story of history so wonderful is exactly that it's fractally deep in detailed facts and connections between them.

On the other hand, just like you can't dip into a novel midway through and expect to appreciate everything, sometimes you need background knowledge and interest before you can properly appreciate a biography. Reilly doesn't explain the facts about World War Two in his autobiography here, even though it looms in the background throughout his time in the Secret Service. If someone doesn't know who (say) Winston Churchill is or what Vichy France is, they're going to fail to fully appreciate this book - but it was still the right decision not to pause to explain them. Similarly, I enjoyed The Heir Apparent much more because I already knew the politics of Europe on the eve of World War I and so could appreciate more how Edward VII was fitting into it; and I enjoyed the biography of Lewis and Tolkien more because I've read their literary works. A biography can attempt to supply some of that - the Lewis and Tolkien biography definitely tried - but it can't fully do that without becoming a general history book.

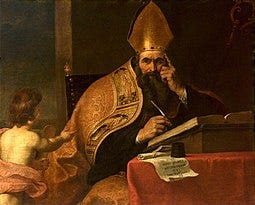

There can be other sorts of biography, too. For instance, I've seen some biographies that try to make those details about the subject's life interesting by analyzing them. This dates back to one of the earliest biographies ever, Augustine of Hippo's Confessions. As he takes us through his life, Augustine comments on just about every incident from his current spiritual perspective and points out how it exemplifies some theoretical point. An instance of (as a young boy) stealing some pears from a neighbor's tree turns into a meditation on sin. Or for a more extreme example, take G. K. Chesterton's Saint Francis of Assisi. At least as much as it's a biography, it's a meditation on St. Francis's life and its significance. Chesterton sprinkles philosophical digressions throughout the book and repeatedly alludes to events he never tells in detail (assuming the reader will have read of them elsewhere). I enjoyed both these books since I enjoy both Chesterton's philosophical digressions and Augustine's spiritual digressions, but I wouldn't recommend either to anyone who doesn't like them. Still, this's a valid subgenre: the story of history can be illuminated by commentary.

In theory, biographies are good. They're loving snapshots by fans of one particular thread of the story of history. But still - despite all these positive examples I gave here, I'm still wary of biographies. They land me amid loving details of historical subplots, which are great if - and only if - I'm in a place to appreciate them.