So Many Worlds, So Few Good Books About Them

Exploring the Many-Worlds Interpretation in science fiction

A few weeks ago, I was browsing at the local used bookstore (a very fun place) when I spotted a title I recognized: The Proteus Operation, a science-fiction novel by James P. Hogan. I first came across it when I was a really young teenager, and my dad had recommended it to me. I liked it then, but I'd thought its theory of time travel to be confusing and overcomplicated. Later, when I reread it in college, I realized it's trying to do something I hadn't really appreciated as a kid: it's actually trying to show the Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics.

So when I found it in that used bookstore, I bought it and read it a third time. And, I realized, it does a better job of exploring the Many-Worlds Interpretation than anything else I've seen... but it still doesn't totally get it. I'll be describing this and several other stories that I think come close, but I'll also explain what's left to be explored and some potential ways to explore it.

The Proteus Operation starts in a world where the Nazis won World War Two thanks to help from malevolent time-travelers from the future. By the 1970's, they and their allies rule most of the world and are poised to conquer the beleaguered United States. In this desperate situation, America sends its own time-travel mission back to 1939 to stop them. Because the Nazi invasion is so imminent, they need to send back the time-travelers before they even take the time or resources to figure out how this time travel works. Just why are things going differently in this new 1939 from the original 1939 they remember - even down to the weather, which they could never have possibly affected yet? And if they do change things, will they have erased themselves or all their friends who stayed behind in the beleaguered 1970's?

Our protagonists eventually find out there're multiple universes, splitting off from each other. This's a real scientific interpretation of actual experimental data (not a "theory" because there's no experiment, even in principle, that could prove or disprove it): the Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics.

Quantum mechanics, it's been shown, can't predict exactly where a particle will be at a given time. What it does is give probabilities: there's (say) a 90% chance the electron will be in this area, and (say) a 5% chance it'll be in this other area, and so on. These probabilities are called a "wave function." Of course, when you actually make a measurement, you find the electron at one specific place. If you keep making measurements, the percentage of measurements where it's in each region will eventually align with the wave function. This is all established science. It works the same with protons, neutrons, and everything else.

According to the conventional "Copenhagen Interpretation" (named because Neils Bohr of Copenhagen famously championed it), when you make a measurement and find the electron at one specific place, the wave function has "collapsed." The problem is, the equations don't explain how the wave function "collapses" and we end up seeing the electron in just one place. So, other scientists have advanced an interpretation - "Many-Worlds" - where the wave function doesn't collapse.

Instead, myriads of different universes split off at every moment, at least one for every point in the electron's wave function, in which the electron is in that point. We only see the electron at one point because we're also entangled in the wave function, and we end up in just one of those many universes. There are other instances of us in other universes seeing it at different points. The same thing happens to every electron in (say) tables or chairs or our bodies, whenever we interact with it.

In reality, there's no way to prove or disprove the Many-Worlds Interpretation, because there's no way to see more than one universe. In fiction, however - as Hogan puts it in his afterword - such "license" is "one of the perks of being a science-fiction writer as opposed to a scientist." I'm convinced this is fruitful ground for many stories. Unfortunately, I haven't found any story that fully explores it.

There're many stories that include multiple universes. To look at one example, Star Trek - in The Original Series alone - gives us an "antimatter universe" with a completely different history, a "mirror universe" where we have evil versions of the same characters, and probably other one-off alternate universes I'm forgetting. However, this isn't even close to the full Many-Worlds.

Under Many-Worlds, we wouldn't have a single mirror universe. We'd have a practically infinite number of them. For example, in Star Trek, we'd have some where Earth had diverged long ago and changed the Federation, some where the Federation had enacted a Proclamation of Evilness last week, and more from every divergence in-between. Thankfully, we'd also have a practically infinite number of good Federations, including myriads which used to be evil but had recently repented. Of course, the universes that'd diverged more than a generation ago wouldn't have a Captain James Kirk or any of the other characters we know. There aren't any "attractors"; once a universe diverges, it can keep getting more and more different.

Subsequent Star Trek shows get a little closer to this by showing us other universes with divergent histories, but they were always presented as one-offs, and (until the recent movies) the alternate histories are destroyed since only one timeline can survive. In Many-Worlds, of course, there'd be uncountable zillions of them which would survive the episode.

Or maybe we shouldn't be giving thanks for the zillions of good Federations. They might be nice to visit, but they make things a lot weirder.

In a Many-Worlds multiverse, you can't change your original timeline by time-travel; you'll just split off a new universe. But also, you can't change anything by any choice you make at all. By definition, every choice made splits off a different universe. It feels like you can decide which universe you're in - but you always split off another universe with another "you" who makes the opposite choice. As Larry Niven puts it in his short story "All the Myriad Ways," when his protagonist (a police detective) is staying late at work:

Gene Trimble thought of other universes parallel to this one, and a parallel Gene Trimble in each one. Some had left early. Many had left on time, and were now halfway home to dinner, out to a movie, watching a strip show, racing to the scene of another death. Streaming out of police headquarters in all their multitudes, leaving a multitude of Trimbles behind them.

This's both a dramatic problem to the story, and a psychological problem to the characters in the story. The reason Niven's Trimble is staying late at work is because, after cross-time travel is developed in that story, huge numbers of people think through the implications of this point and decide that everything they do is meaningless. So, they start committing random crimes and killing themselves. Crosstime travelers, on average, last less than half a year before suicide.

Niven writes this as a psychological short story. If you're building a longer story about the Many-Worlds interpretation, you can avoid this issue. But if you want your story to really explore the implications and dramatic possibilities of the Many-Worlds interpretation, you should try to address it.

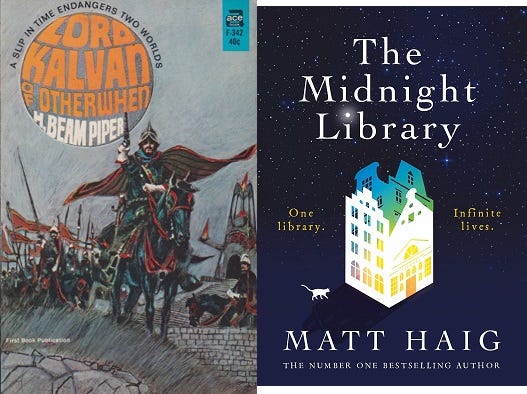

Most stories with alternate universes don't mention it. Even in Hogan's The Proteus Operation (the best long exploration of Many-Worlds I've found) and H. Beam Piper's Paratime series (which contains a few good parts, and is also good as a story), none of the characters react to the knowledge that, in other universes, each of their choices were made differently. In Paratime, we have brief mentions of our protagonist Vernken Vall seeing his coworkers in timelines nearby his home timeline as he's returning, but this's just a throwaway reference; the implications aren't pursued. But Piper's Vall should know that his coworkers there were just as real as his coworkers in "his home timeline" (and that he won't keep one single "home timeline"; that itself is splitting.) In The Proteus Operation, Hogan's heroic Wingate realizes the implications of the Many-Worlds Interpretation before any of the other characters, so he should know that there's also a universe in which he helped Hitler, and another in which he himself conquered the world as an evil dictator... but he doesn't seem to appreciate this. At least, he doesn't mention it or give any emotional reaction to it.

Aside from Niven's short story, there's one published book which does at least present this problem as a question: The Midnight Library, by Matt Haig, where the protagonist sees her life in dozens of alternate universes spawning from different choices she might have made in her past. The lesson she takes from this is the infinite possibilities that lay before her. Unfortunately, she doesn't consider the implications of how her future choices would also spawn further branches. This might be because the plot distracts her, or it might be because she isn't used to pondering deep philosophical questions. But also, admittedly, the whole universe-hopping apparatus turns out to be only debatably real within the book.

But there is one other decent attempt that I've seen to actually explore the significance of individual choices under Many-Worlds. Surprisingly, it's an Animorphs fanfic, The Parallel, by fanfiction.net user "Qoheleth." After our protagonist meets her divergent-universe counterpart, she contemplates:

It had made me think of all those other universes (decillions of them, Chester had said) that had replicas of me in them: were all of them me? Was my soul, my essence, everything that made me me, somehow spread out like butter over a million billion girls on a million billion Earths? When I got to heaven, was St. Peter going to say, "I'm sorry, miss, you're going to have to wait to get in until the rest of you get here"?

No, all right, that was silly - but still, it was kind of a disturbing thought. I mean, I had always been taught that your choices mattered, that a man would suffer loss if his building burned - and now Chester was saying, as far as I could tell, that, if a man built something inflammable, God would just spin off another universe in which he built something that wasn't inflammable. That didn't seem right, somehow.

Our protagonist puzzles over this until being distracted by the plot. What settles her mind is another shortcoming of our understanding of physics.

We have wave-function equations for what proportion of alternate universes have electrons and protons in different spots, but what proportion of alternate universes have different human choices? We can be pretty sure there's at least one universe where Gene Trimble leaves his desk at the police station early to go to the movie theater, but how many - what proportion of branching universes - are they?

Unfortunately - or perhaps fortunately - physics can't help us here. We don't know how human choices come about in the brain. If they're completely caused by physical parts of the brain, then of course each choice will split off some number of alternate universes, the exact percentages depending on how the brain works... and what sort of person you are. We know that some people are more likely to make some choices than others, so we can say (for example) that in the universes diverging in May 1940, Churchill surrenders to Hitler much less than half the time. One could perhaps build a moral theory off of this, where you would try to be the sort of person who makes the more moral choice in more universes. It still sounds uncomfortably deterministic, but no more so than most materialistic moral theories.

The moral significance of individual choices does come up at one point - and only one - in The Proteus Operation. One character is staggered by the sheer number of universes (so many that, compared to finding one single universe in the whole multiverse, "accidentally finding a needle in a haystack would be a dead certainty"), and he questions why they're bothering to fix the one timeline they're in. He gets two responses. First, they're in it, and they want a better future for themselves. But second, he's reminded that any one timeline saved might seem insignificant, but it means everything to its inhabitants.

One could decide to morally ignore the many other worlds like this, and one could write books about people doing that... if we still pretend a person's choices have meaning in the many worlds.

Of course, if one actually assumes non-material souls with free will, the question becomes much easier. Our protagonist from The Parallel later settles on that, after seeing her alternate-universe counterpart again:

I wondered, for a moment, whether I would have been that lost and paranoid if I'd been her. Then, the next moment, I realized: of course I would have been, because I was her. The only difference between the two of us was the events we'd lived through; if those events had happened to me - or to my part of me, or whatever - then I'd have done exactly what she'd done.

I remembered those metaphysical reflections I'd had, the night I'd been flying back to the house with Anifal: would my choices and my double's somehow negate each other at Judgment Day? Now I realized that I'd been missing the point. The choices that made universes couldn't be the big, obviously important ones... Then your soul was involved - and... you can't split a soul. So, in every instance where it really mattered, my double's free will wasn't a rival to mine: it was mine. I'd chosen to be that girl down there; I'd chosen the vicious, animal hatred I'd seen in her palant thread. It wasn't just a case of "there, but for the grace of God, go I"; I had gone there, grace of God and all...

And on the heels of that thought came another one: And if I'm the grace of God for my double, I should act like it, shouldn't I?

"You can't split a soul," our protagonist concludes. If souls are non-material, then we can assume they aren't subject to quantum wave functions, so choices made in the soul won't split off alternate universes. This interpretation holds together consistently. It emotionally fits too, and to emotionally fit even better, we can follow "Qoheleth"'s lead and assume that the choices made in the soul are major moral decisions.

So, we can have a multiverse where some choices are still meaningful. Wingate never helped Hitler; the murderers Trimble is investigating either murdered in every universe or - if not - it tells you something that, for them, deciding to murder someone isn't a major decision. (And within the stories, it remains possible that both of these are true. If so, it's too bad for Trimble that he never realized it.) This lets you write a good, satisfying story that explores the implications of the Many-Worlds Interpretation.

Is it true? Well, is the human soul real? Is it made up of particles subject to nondeterministic wavefunctions? And on top of that, is the Many-Worlds Interpretation even true? Myself, aesthetically, I feel something like the Copenhagan Interpretation is more parsimonious. But that's just my guess. We don't and can't know for sure.

It's too bad the only stories I've seen even ask about the significance of individual choices are one Niven short story, and one online fanfic. And it's also too bad that the fanfic is the only one that's given the question an answer that isn't meaninglessness.

So if there were a book that truly tried to explore the implications of the Many-Worlds Interpretation, even more so than The Proteus Operation and The Parallel... what might it be like?

To start with, we'd encounter not only far-removed universes but also additional versions of our protagonists and antagonists. What's more, we'd see versions who've diverged after the start of the narrative. If there are versions who make different major morally-significant decisions, then we'd see some of those too, and our protagonists would grapple with the implications. If not, their absence would be remarked on and those implications explored.

What inciting event could launch this plot? A comic-book-style villainous scheme to conquer the multiverse wouldn't work; the multiverse is so huge that any such scheme would be laughable. The conflict in the plot would have to be limited to just one sheaf of universes, such as The Proteus Operation's time-traveler-spawned World War Two, or The Parallel's alien invasion (which it takes from canonical Animorphs). Of course, someone might question whether this's significant against the scale of the multiverse, but The Proteus Operation's answer could work well.

Even aside from the plot, exploring the multiverse like this would give great potential to explore characters. If we do impose the restriction of The Parallel's view of souls, where we mark morally significant decisions by having universes not split on those, then that gives us an even greater window into characters.

I would love to see a book like this. Unfortunately, if it exists, I haven't encountered it. Perhaps someday I'll write it. But it should exist; many like it should exist. The Many-Worlds Interpretation is crying out for a good book to explore so many of its implications.

Greg Egan is a must read for implications of MWI. “Singleton” and “Schild's Ladder” come to mind.

(I cannot find *anything* in Substack's documentation about which forms of text markup are acceptable in comments. Well, if it comes out as raw HTML, at least it will be clear what was meant.)

---

>><i>We don't know how human choices come about in the brain. If they're completely caused by physical parts of the brain, then of course each choice will split off some number of alternate universes, the exact percentages depending on how the brain works... and what sort of person you are. We know that some people are more likely to make some choices than others, so we can say (for example) that in the universes diverging in May 1940, Churchill surrenders to Hitler much less than half the time. One could perhaps build a moral theory off of this, where you would try to be the sort of person who makes the more moral choice in more universes. It still sounds uncomfortably deterministic, but no more so than most materialistic moral theories.</i>

Huh, my main problem with it is exactly the opposite: that's the *most* comfortable level of determinism, more so than levels above *and* below it, and as such it seems too good to be true. The multiverse was not made for me, and I would find it suspicious if it just *happened* to work the way I intuitively feel it ought to work.

I'm not especially disturbed by the idea that someone with perfect knowledge of my mind could perfectly predict how I would react to a given situation: after all, in order for me to be said to have made a decision, it has to *matter* that *I* was the one making it. If each of my decisions is simply the aspect of my fundamental essence that that precise situation evokes, that seems basically fine.

(The main problem I'd have with living in a fully deterministic singular universe wouldn't be the lack of free will (why would I *want* the ability to go against my own nature?), but something more like a lack of quantum immortality. Variance is inherently (albeit not infinitely) bad: in any given dangerous situation, I'd rather have a guaranteed small fraction of my forks die than a small probability that all of me dies†. "Live in the worlds in which you live††" is more comforting if it's literal, even if it's still a useful heuristic for a singular universe.)

No, the *really* viscerally disturbing ontologies are the infinitely-branching ones like in "<a href=https://www.uncannymagazine.com/article/and-then-there-were-n-one/>And Then There Were (N-One)</a>". (I'm surprised you didn't mention that one: feels like it was all over the place a couple of years ago. Maybe it was just an accident of whom I happened to be hanging out with.) None of those Sarahs have ever actually made a decision in their lives: *random noise* made the decisions, and they were just along for the ride.

---

†I was rather confused by <a href=https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/david-wallace-many-worlds-theory-of-quantum-mechanics/>reading</a>:

"<i>Maybe you now think of a time you drove home drunk without incident as being worse — because there are branches where you actually killed someone. But David thinks that if you’d thought clearly enough about low-probability/high-consequence events, you should already have been very worried about them.</i>"

Somebody clearly has very different intuitions.

(I'm plenty worried about low-probability/high-consequence events, FTR)

††more commonly phrased as the lower-stakes version, "if only one card can win you the game, play as if that will be the next card you draw"