Short Reviews for May 2025

Have Space Suit Will Travel; Too Many Magicians; After Yorktown; Civil Religion and the Presidency

Have Space Suit, Will Travel, by Robert Heinlein (276 pp; 1958)

Who should read this? Someone who likes Golden Age pulp sci-fi.

When I first read this book as a kid, I loved it. Now, it doesn't hold up to the memories I had, but it's still fun.

Our protagonist Kip, growing up in what feels like stereotypical '50's small-town America, yearns to go to space - to join the growing city on the moon. Having resourcefully gotten his hands on a spacesuit, he refurbishes it for fun as if he were going to use it in space - which Heinlein lovingly describes. And then, that stands him in good stead when he's abducted by aliens, tries to escape together with an also-abducted genius young girl ("Peewee") and a more-friendly alien ("The Mother Thing"), and then ends up representing Earth before the galactic Security Council.

Kip's an engaging protagonist, and far and away the best part of the book. Peewee is a memorable character whom I liked as a kid, but on reread now she appears annoyingly childish and self-defensive both when she does know what she's doing and when Kip knows more than her. The aliens and the plot don't stand out as poorly done - Heinlein does know what he's doing - but there's nothing that stands out as great about the aliens either. The Mother Thing is still a great concept, but it doesn't quite connect notably to the plot in my opinion.

I'm left with a great character, a fun story, and some interesting questions about the aliens' ideology: At some points it seems to say things about species self-defense which Heinlein expanded on later in Starship Troopers, but they're acting much more cooperatively than anyone in Starship Troopers; what might this imply? But here, Heinlein doesn't answer those questions.

What we do get is a fun adventure.

Too Many Magicians, by Randall Garrett (342 pp; 1966)

Who should read this? Someone who wants a fun, quick fantasy mystery read.

This's the only novel Garrett wrote about his detective Lord Darcy (along with some short stories), set in a world with magic studied like science, medievalesque flavor, and vaguely-Victorian technology. Our detective is a nobleman of the Anglo-French Empire; his aide and sidekick is a sorcerer who's always ready to explain his craft. The magic is usually, but not always, flavor and tool for detection.

The novel's an extended mystery which brings in threads from most of the short stories to involve multiple murders, a sorcery convention, international espionage, and more. We get some interesting characters (some recurring), developed at a little more length than in the short stories. Also, there're some fun side-references such as "Sir Gandolphus Grey".

What stood out the most from the short stories is their fundamental conservativism. It's not just that the stories treat the pseudo-medievalesque social system as a good thing; it's that it always works out in the stories! There are dishonorable individuals, but the larger system is ready to clean up the messes they make. This isn't the only setting where (in one short story) our detective hides the real culprit, but it's the only one where I've seen him explain that afterwards to his boss who agrees it's a good thing!

This novel starts to give a more nuanced view of this: Apparently, the scientific investigation of magic has yielded ethical laws which aid in keeping the government trustworthy... but how it does that is sadly underdeveloped, because we also hear that the government must be quick to drum out any official who does act unethically. (As we see in this story!) I'd like to see more development of how these concepts interact, but Garrett doesn't seem to show that.

Like the short stories, this's not very deep, nor are any of the characters well-done in multidimensional ways. But it's a fun quick read.

After Yorktown: The Final Struggle for American Independence, by Don Glickstein (432 pp; 2015)

Who should read this? Someone who wants a dark-pitched outline of other theaters of the American Revolution, which focuses on the war not the ideology.

This book is mistitled. The first several chapters are indeed about the skirmishes and bitter guerilla war in the southern states after Yorktown, but then it moves on to other theaters of the Revolution - the frontiers, the Caribbean, Gibraltar, India - both before and after Yorktown.

The dust jacket advertises the book as asking how you end an endless war. That's a book I'd like to read - but that isn't this book! Presumably that book would talk more about the commanders and the political leadership; this book instead is talking more about the bitter fighting on the ground.

And it was bitter. I now see more of where Adair got her setting for Paper Woman - the long, resentful guerilla fighting in the southern states was very different from the conventionally-told battles of the war. (Though, I still don't see Adair's protagonist anywhere!) That's the dominant message I got from the first half - that the long years of war had stirred up such enmity that would not rest. Even the Revolution, with such a noble cause, had brought people there.

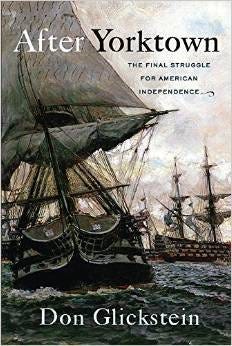

Civil Religion and the Presidency, by Richard V. Pierard (359 pp; 1988)

Who should read this? Someone who wants to dig deep into various Presidents' statements about their religious faith.

Civil religion, as Pierard (a Baptist university professor writing in 1988) tells it, is religious statements, claims, and exhortation that are publicly displayed in society (especially by public officials) with the assumption that everyone or almost everyone can join in it. In many premodern societies, it was identical to some specific religion, such as Roman paganism or Catholic Christianity; in modern America, it's most pointedly not any specific religion but borrows elements of - traditionally - multiple branches of Christianity.

Pierard talks some about religion in America at the Founding, and then goes through several Presidents to search out their personal religious beliefs and how they participated in civil religion. He makes interesting points about how America's civil religion has shifted and become more broadly inclusive, and about how Presidents can engage in civil religion as either a prophet or a priest. He favors the prophetic role, and I see why - but that assumes the prophet is speaking the truth! Have not both Biden and Trump acted as diametrically-opposed "prophets" on race relations? Does not most of America hate at least one of them as a prophet?

His telling of different Presidents' religious lives is also interesting. All of them called themselves Christians - yet for myself, after reading Pierard's telling, I hesitate to call some (like Wilson) Christian, and absolutely would not give others (like Eisenhower) that title.

That said, despite the topic having some interest, the book spends most of its time recounting details and public or private statements of the different Presidents. As a historian, this's good because it gives you the original data. Yet, this isn't a book for casual reading. Pierard gives very few conclusions or arguments of his own, save at the very beginning and very end. It's mostly a compendium.

Oh my, I hadn't been able to find all the Heinlein's till I got to college at UB. (Buffalo) 1977. And Lockwood library had an awesome fiction collection. Scifi was in the basement (of course) But I still recall staring at these immense stacks and thinking, 'this is more books than I can read'. Anyway I started reading "Have Spacesuit will Travel" sitting on the floor and eventually got up and found an open 'cubbie' study hole. And finished it off. "Wow what a nice tale", I thought to myself. That's still how I think of Heinlein, he wrote nice tales/ stories. Stories that I would somehow like to be a part of.