Accelerando, by Charles Stross (415 pp; 2005)

Who should read this? Fans of classic science fiction.

I put it off for a while, but now I've finally read Stross's classic novel of the Singularity. The story stretches over generations and centuries, from what seems like the near future through mind augmentation and the spread throughout the Solar System to when transhuman entities finally push the quasi-post-humans out of the System. The characters and scenes are vivid, and the twist at the end fits perfectly into the themes while filling all sorts of moments with new significance.

Some of the worldbuilding seems quaint in this day of LLM's, when we know that real AI is nothing like uploaded lobsters spontaneously developing consciousness and superintelligence. But, I accept it as a classic sort of sci-fi worldbuilding, even though the quaintness here is more explicit than usual.

However, Stross's characterization is sparse here, and the characters' actions seem disconnected from events. Perhaps this's inevitable; Stross's theme is that the Singularity will make human actions irrelevant. But, it's only in the last couple chapters that Stross leans into it being a tale of human survival, and specifically this one family, amid the Singularity. Until then, he's trying to simultaneously tell the story of this one family and tell a larger-scale story of the Singularity itself. He can do that because this family is often there at significant moments and looks like they're taking significant action. But it means he isn't telling either story as well as he could if he leaned into it.

But still, I enjoyed reading this. So many scenes are vivid and beautiful. Manfred's madcap rush toward progress, Amber's pseudo-Sun-King kingdom on Jupiter, the AI cat, the posthuman nonconscious lawyers... all these and more are fun and wild images that make me very glad to have read this.

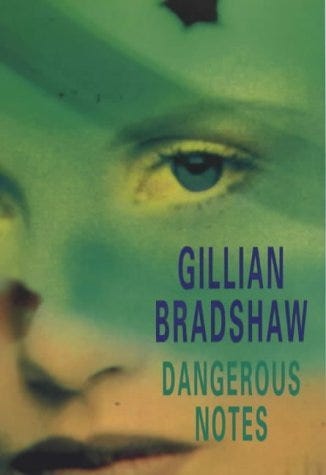

Dangerous Notes, by Gillian Bradshaw (288 pp; 2001)

Who should read this? People who like dramas with philosophical implications.

Gillian Bradshaw doesn't just write historical fiction; she also writes vaguely-modern-day thrillers. Usually I don't like them as well, but this time I did.

Our protagonist, a college-aged violinist, received a novel brain treatment as a child - but recently, the procedure has been found to result in episodes of lapsed consciousness that occasionally turn violent. The legally-mandated study of her brain turns up surprising things about how her brain relates to music. Meantimes, the neuro-researcher leading the study turns out to have mysteries and secret motives of his own. And, all this raises questions in her mind about her self-identity and what makes her herself.

The exploration of personal identity and responsibility here is very well done, and held my attention throughout the book. Bradshaw brought in very good twists, and I liked her ending - in every respect, but I'm going to call out that the end of the romantic subplot was a pleasant surprise.

That Man Haupt: A Biography of Herman Haupt, by James Ward (278 pp; 1973)

Who should read this? People who enjoy delving into nineteenth-century America.

After reading several books about railways in the Civil War, I read this biography of Gen. Herman Haupt, head of the US Military Railroad.

His life is an interesting story. Sort of like Churchill, his life contained a lot of failures - until he ended up having just the right talents for the important job he'd come to. And also like Churchill, he got turned out of that job at an early moment: for Haupt, while the war was still going on, but after he'd built up the US Military Railroad with such talent and demanding procedures that it could run well without him, keeping the US Army supplied beautifully throughout the war.

And then he returned briefly to the impossible job he'd been throwing himself at before the war: attempting to dig a tunnel in Massachusetts that would eventually be completed decades later with new technology. He would briefly do more great work managing the Northern Pacific Railroad, but largely his life was marked with failures.

Haupt had beautiful talent at managing and some at engineering, but very little at politics. That sank him repeatedly, as he failed to identify bad partners and failed to befriend management (whether influential officers in the Civil War, or the board of the Northern Pacific). He died near bankrupt, musing over how the world was developing in the wrong way.

But, for a few shining years, Haupt was exactly the right person in exactly the right place to do great good.

The US Army GHQ Maneuvers of 1941, by Christopher R. Gabel (235 pp; 1991)

Who should read this? People interested in the history of the US Army.

This's an official US Army history of the 1941 Army grand maneuvers and training plan, building up the US Army before entrance into World War II. As an official history, it focuses on the details of how things were set up, assumes the reader knows the background of what was happening in the world and America at the time, and spends no time setting up characters and very little time talking about their motivation. I was fine with that - but it's a very specific sort of book. I'm glad not most books aren't like this.

It opened my eyes to see what was involved in building the Army even beyond basic training: the need to train bodies of men to work together, the need to train brand-new commanders at commanding, and the need to test military doctrine. Though Gabel doesn't go into this, this shows how much America has been protected by the oceans: unlike Poland or France or even Britain, we got these years to train an army before we needed to send it to fight the war.

Gabel questions how useful these large-scale maneuvers actually were. Doctrines weren't fully evaluated, many of the senior officers never actually fought in the war afterwards, and all the units involved were gutted afterwards to help train the even-newer units raised after Pearl Harbor. But, he concludes they were worth it to train the commanders who did fight and to test commanders and doctrine to at least some extent. Having read in other books how clunky the fighting in Africa actually was, I'm wondering if more such maneuvers could've been useful.

Charles Stross has Accelerando free on his blog, along with links to free downloads of some of his shorter fiction. <https://www.antipope.org/charlie/blog-static/fiction/online-fiction-by-charles-stro.html> His blog is also fun and interesting, and subdivided by topic.