Short Reviews for June 2024

The Emperor in the Roman World, The Making of Shakespeare's First Folio, What Monstrous Gods, Glasshouse

The Emperor in the Roman World, by Fergus Millar (656 pp; 1992)

Who should read this book? Students of the Roman Empire looking for material; also history fans looking for a wealth of anecdotes.

This's a study on how the Romans themselves viewed the role of the Emperor, looking at the Roman Empire specifically without relying on extrapolations from pre- or post-Roman monarchies. The position of Emperor had a unique history; to what extent was that reflected in practice?

Millar answers this by six hundred pages of anecdotes about Emperors, organized topically: appointing officials, receiving petitions, consulting with friends, conducting trials, et cetera. From these, we can see what the Emperors did and, also, what people in those stories presumed they would do. Historians will find this collection very valuable; I let Millar carry me along with his conclusions and used this mostly to metaphorically spend time in Rome. A limited slice of Rome it was (one of Millar's points is that only people or groups of some standing were allowed to write to the Emperor), but still a significant and fun slice.

In conclusion, the Emperors were - from very early on - autocrats; and people related to them as such. In the East, used to monarchies, people frankly called him a king and assumed (correctly) he would do all the things that an Eastern king usually did. And then, after a generation or two, he started doing those same things in the West too. The precise way in which he did things was very similar to other upper-class Romans, but that barely concealed his unique power.

The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio, by Emma Smith (277 pp; 2016)

Who should read this? People curious about the world around Shakespeare.

This's a book about the making of a book - the "First Folio" of Shakespeare's plays, published posthumously. It's the only surviving copy of many of his plays, including ones now as famous as "Macbeth". Notably, Shakespeare's friends who put it together had it published folio-sized, targeting a more respectable market that would normally think it beneath themselves to notice plays. This tactic worked - and prefigured Shakespeare's current status as high literature.

Smith's book meanders around topics associated with the First Folio and playwriting in Shakespeare's day. It's not the best written, but most of it was interesting and new to me. Among other things, I learned a lot about Jacobian-era publishing and copyrights - contrary to what I said earlier, apparently there was a rigorous concept of rights to publish individual plays, enforced within the Stationers' Guild.

Also, I'm intrigued by how much we still don't know. Smith points to evidence of robust revisions between first staging and publication, and between prior publication and the Folio for those plays that had been published before. What then represents the author's intent? According to Smith, we can't say Shakespeare had a single intent. Perhaps, then, more modern adapters are following in Shakespeare’s tradition?

What Monstrous Gods, by Rosamund Hodge (368 pp; 2024)

Who should read this? Fans of dark fantasy, and fantasy with religious elements.

After restoring the ancient gods-blessed royal family (by killing the heretic sorcerer who put them in enchanted sleep), our protagonist is expected to herself make a pact with a god and help bring back their blessings to the realm... only to find that these gods are more inhuman, and their "blessings" more painful and monstrous, than she had appreciated. And, the ghost of the sorcerer she killed is haunting her... and insisting that his heresies are being proven all the more by how monstrous the gods are being. But despite all this, she's falling in love with him.

I greatly enjoyed this book. Our protagonist's yearning for a safe place to belong, and repeated sense of betrayal - by the nuns who raised her, by the royal family, by the gods, and more - is so excellently shown.

Another excellent element I appreciated is how Hodge depicts the sorcerer's persecuted "heresy" as - in fact - Christianity. It's never explicit. Being in a a fantasy counterpart world which uses next to none of the same names, we never hear the words "Christianity" or "Jesus", and our protagonist is herself devoutly pagan. But that merely helps the story. Hodge shows the contrast between these pagan gods who give their worshippers deadly gifts and the rumored one god who himself died to - so our protagonist heard - give good gifts.

This sort of worldbuilding, character, and perspective are things I would love to see more often.

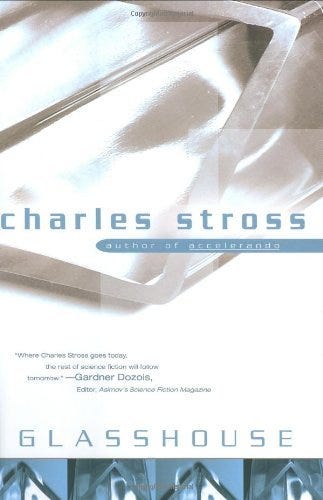

Glasshouse, by Charles Stross (335 pp; 2006)

Who should read this book? People who like a gradually-unfolding science fiction conspiracy story, and who can endure an author dropping anvils.

In a near-post-Singularity society, in the aftermath of a war against a mind-controlling computer virus, our protagonist joins a social experiment trying to recreate and study the 1950's. But, the experiment may be a cover for a group trying to reintroduce that mindvirus.

Half of this book, I really liked; the other half, I really disliked. Stross has an obvious ax to grind against the 1950's, their social norms, and their social conformity. Even though emphasizing these elements beyond the actual 1950's has an obvious Watsonian reason, the differences between this experiment and the actual 50's are never pointed out. It's pretty clear the author hates 1950's culture himself and doesn't mind letting us all know that.

But, the plot and the rest of the worldbuilding save the story for me. The Curious Yellow mindvirus and the fight against that - both in story and backstory - is excellently done. We don't see the outer world itself in the story, but we're fed enough about it in backstory to feel we understand it decently, and feel the horror when we read about the virus tearing it apart. Yes, of course the A-gates would be a monoculture vulnerable to those. And of course petty tyrants would spring up and use it for their own ends.

And of course, after the war, people like our protagonist would feel lost. I love the gradual unfolding of what all this did to our protagonist. The villains trying to use that perfectly fit, and the ending was well-earned.

So all in all, despite the flaws, I do think this's one of Stross's best books.

In what is becoming an annual tradition (last year was "Epilogue"), I scanned your short reviews for the last six months and asked for one of the books for Christmas, so I would have something to start reading on Boxing Day.

I couldn't put What Monstrous Gods down. Lovely time. Never heard of it, never would have heard of it, and wouldn't have trusted it if I had, sans your recommendation. Thank you!

I did not expect that sentence to end "...trying to recreate and study the 1950's.", LOL! Some cognitive dissonance with the first 2/3 of the sentence.

Okay, can I geek out on a thought about the 1950s? (in America.) Something I know rather little about, but continue to have evolving opinions about. Started out more positive, now settling into "Yeah, but high standards people were held to in public doesn't mean it was great for people when they got back home, behind closed doors." And also, just the thought of so much technology suddenly (?) available to take over women's work... whose labors working at home could previously have been celebrated as awesome... and the cultural attitude of "yay, I now have technology; that means I can kick back and take it easy" and therefore probably a lot of women failing to find new purpose to apply their newly-freed-up time to.

Most interesting perspective I heard about just getting an "eye level" view of being a kid growing up as a baby boomer... was the image of already-huge classrooms, and cramming a few extra seats in the back row when more students showed up. Getting turned away from baseball teams because there were SO MANY kids trying out => there were lots of kids better than them. I wonder if rampant conformity was just a kinda-straightforward response to the then-current setup of resources. Like, you just kinda would rationally feel more "replaceable" (?) in the public sphere, at least. And everyone else looking on would also feel that, on a gut-level. Public knowledge. (Also, conformity to what you can't change in terms of external circumstances doesn't NECESSARILY mean that you're producing a generation that has greater-than-average inward conformity, in their private thoughts. Perhaps? I really don't know.)