Short Reviews for July 2025

Glory Season, Tainted Cup, William Pitt the Younger, White Eagle Red Star

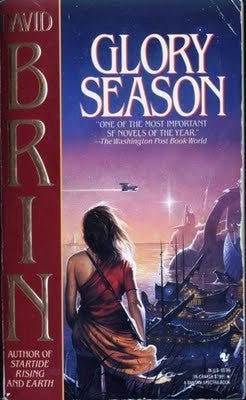

Glory Season, by David Brin (772 pp; 1993)

Who should read this? People interested in social-dynamics-focused science fiction.

On the colony planet founded by radical feminist genetic engineers, women can give parthenogenic birth to clones, and the great houses of clones rule politics and economics. Our protagonist, not a clone, is cast out to find her own way in the world... and (after trying several economic nitches) ends up entangled in a conspiracy rescuing a visitor from offworld.

This isn't a study of feminism; it's a study of social and gender relations in this very unusual hypothetical. Brin doesn't grind any axes, except the ax of "incentives matter; design around them" - which he keeps coming back to. This planet has been put by design into a stable equilibrium, and Brin keeps showing us how it's stable.

The best part by far is the tour of the world, which Brin's plot is designed to show us so many different parts of. Second is our young protagonist's character growth as she questions more and more of what she's grown up with... but legitimate questioning, rather than throwing it all out. Brin the author obviously wouldn't choose a low-tech world fixed in an equilibrium, and some of the characters in the book wouldn't either. But I can see how our protagonist loves so many parts of her homeworld, throughout the book.

I do recommend this.

The Tainted Cup, by Robert Jackson Bennett (410 pp; 2024)

Who should read this? People interested in original fantasy worldbuilding with nicely-done plots.

This mystery set in a fantasy empire has fun characters, exciting plot, and original interestingly-built worldbuilding. It isn't the best as a mystery, but that's a small fault among everything it does do well.

Our narrator, clearly a Watson not a Holmes, is assistant to a talented oddball detective sent to solve the poisoning of an Imperial Engineer with a magical poison. The plot turns out to be much bigger than it appears, snowballing into summoning a leviathan attack and implicating one of the major political houses of the Empire.

Little of the clues are telegraphed in advance, and much of the explanation depends on details we don't yet know, so we're necessarily almost as ignorant as our narrator - but as they're revealed, they build out the worldbuilding very engagingly. We start knowing enough; we learn more as we go along, and we enjoy the walk to get there.

We're left with intriguing questions about the Empire. Our narrator ends up soured on the Empire due to its corruption, but still the book seems to be portraying it as good on balance - which I agree. As the refrain goes, if the Empire stands up to protect people from the regular magical leviathan attacks, it's done well.

This well deserved its Hugo nomination, and I'm looking forward to reading the sequels the author set up for.

William Pitt the Younger, by William Hague (652 pp; 2004)

Who should read this? People familiar with the history of British politics who want to dig in more.

Perhaps a prominent Conservative politician in the modern UK is just the right person to write a biography of Pitt the Younger. Pitt didn't just center his life around Parliament; it almost was his life. He's among the youngest ever MP's, remains the youngest ever Prime Minister (by far - at age 24!), and died in office at age 46 as the longest-serving Prime Minister. In the meantime, he didn't have any hobbies, barely attended to his personal business, and barely had any friends who weren't also involved in politics. A biography of Pitt is necessarily a biography of his political life.

Hague understands, if not sympathizes, with Pitt's monomaniacal focus - in office, he testifies, one hasn't the time to build new hobbies; and Pitt was in office for most of his adult life. It may have killed him, but it also defined him.

What Hague is more reserved on is how much good Pitt actually did for Britain. He reformed British government, but most of his major projects (such as abolishing the slave trade or giving Catholics political rights) weren't accomplished till well after his time. Could someone else have done more? Hague doesn't answer, but he raises the question. And that's what most lingers in my mind. Pitt did so much, but what did it actually mean in the end?

White Eagle, Red Star: The Polish-Soviet War 1919-1920 and the Miracle on the Vistula, by Norman Davies (336 pp; 1972)

Who should read this? People interested in World War I who want to see its aftermath, or people interested in the history of Communism, or interested in nationbuilding.

After World War I and toward the end of the Russian Civil War, the brand-new Polish and Soviet states fell into war with each other. Their mutual border was clearly unsettled, with various independent warlords and villages acknowledging neither nation; neither trusted the other; ethnic tensions among the ethnically-mixed population were high amid the anarchy; and the Soviet government was heady on thoughts of world-sweeping Communist revolution. So often all this unsettledness gets swept over, because it did get settled within a few years... but it was real, and it took this war to finally settle it.

The initial Polish invasion of the Ukraine failed, Davies argues, because Poland intended it as nothing more than a decoy to gain time. The subsequent Soviet invasion of Poland, Davies argues, failed on the doorstep of Warsaw not by a miracle of fighting but by a miracle of repositioning - the Polish army moved to attack the Soviet flank faster than they'd thought possible. But just as significantly, contrary to the Soviet army's expectations, they weren't welcomed in by Communist revolution.

I came out of this agreeing with Davies this war should be talked about more. It demonstrated that there wasn't going to be a world revolution, and thus sparked a great repositioning of Communist ideology. And also, it gave the Polish state the unstable core idea that helped lead to the instability of interwar Eastern Europe.

I read White Eagle Red Star, partly because I've enjoyed some of Davies' other books. The Polish-Soviet War of 1920 is involved in my best solution to an alt-history puzzle. In WW2 the western allies teamed up with one dictator to defeat another: Stalin over Hitler. The puzzle is to ask what it would take to fight the war the other way, teaming up with Hitler to defeat Stalin. My speculation is that if the Soviets beat the Poles in 1920, that puts the expansionist Soviet Union (or a Soviet puppet state) right on Germany's doorstep, and everyone to the west of that will be more worried about a chain reaction communist revolution than in our timeline. Maybe the Soviets have more conquests in eastern Europe before WW2 kicks off. (There was quite a bit of extended chaos in the east after WW1; you could even say that WW1 didn't come to a definite end there as it did in the west. So if the Poles didn't stop the Soviets...) It is plausible then to imagine WW2 as a fight between Central and Western Europe on one side and a more threatening communist East on the other.

*2025?