Short Reviews for August 2024

Montaillou, Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, The Algebraist, Howl's Moving Castle

Montaillou: The Promised Land of Error, by Emmanuel le Roy Ladurie (383 pp; 1975)

Who should read this? People wondering how medieval peasants actually lived and thought.

In the early-1300's southern French village of Montaillou, where Catharism was extremely popular until a new bishop brought the Inquisition to arrest and investigate every adult in the village. What we get from this sad tale is an unequalled look at the daily life of a medieval village and its religious sentiments.

The big surprises I got about village life as a whole are how strong the household divisions were (contrary to England, where adult children usually moved into their own houses); and how they usually weren't anywhere close to starvation and (e.g.) had two-story buildings and meat to regularly eat (even sometimes on fast days).

But the really interesting things were in religion. We hear of some people offering theological hottakes that'd be right in place on Tumblr today, like how the soul is nothing but wind because it leaves someone with their last breath. As well as the Cathars, the Inquisition also turned up a fullblown atheist materialist, and a possible pantheist.

We hear of even many Catholic villagers respected the Cathar hermits, because (most of them) lived a visibly holier life than the Catholic priests. Now, Catharism said that all meat-eating is sin, and all sex is sin. So we get a story of someone who asks a Cathar hermit about eating meat on a fast day, gets the response "it's no worse then than any other day," and does it. And we also get the guy who publicly keeps a mistress, and defends himself with "the Cathars say it's no worse than sleeping with my wife."

This's a fascinating look. The author doesn't venture to guess how normal this is for medieval villages; there was definitely at least an unusual level of Catharism. But I can't help but wonder.

Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917-21, by Colin Darch (240 pp; 2020)

Who should read this? People interested in the history of Ukraine, the Russian Revolution, or political leftism and anarchism.

In the midst of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, a Ukrainian industrial worker and committed anarchist named Nestor Makhno gathered and led his own anarchist army, in the name of the "free soviets" of local Ukrainians he helped organize against the demands of any higher state.

Makhno refused to ally with any of the White armies, saying that the Bolsheviks must be resisted only from the left; the Revolution must not be turned backwards. In fact, he fought the White armies, and briefly allied with the Bolsheviks against them. In part because of this, he failed. As soon as the Whites were suppressed, the Reds turned on Makhno, mopped up all his support, forced him into ignominious exile.

This book tells his military story, and attempts to discern the political story which's been buried under decades of Soviet and now Ukrainian propaganda. His armies were more than bandits, but it's unclear how disciplined - we have unreliable sources that point to their regular looting and other misbehavior.

But, it argues, Makhno must be understood primarily as an ideological anarchist. I agree: no one but a committed leftist would have refused to fight the Red Army until no other option presented itself. He kept trying to ally with them, but they kept refusing to give anarchism any respect or recognition. Perhaps any other option would also have failed, but I believe this one’s failure was predictable.

The Algebraist, by Iain M. Banks (434 pp; 2004)

Who should read this? People who like copious worldbuilding and don't mind poor plot

In a space-opera galaxy, this one solar system that's been cut off from the galactic wormhole network is facing invasion. They send our young protagonist, who's a friend of the "Dwellers" who live in gas giants and largely ignore the rest of the galaxy, to see if he can get from them the keys to their rumored secret second wormhole network. But, further wars erupt, as do further escapades with the unexpectedly-technologically-advanced Dwellers.

Sadly, the plot doesn't match up to this exciting setting. I had a hard time following Banks' many characters and meandering subplots. But worse, the ending feels disappointing and cynical. Our protagonist really hasn't achieved anything. Our protagonist's whole side of the war feels futile. Victory, overall, doesn't come from our protagonist or any of the characters we've met and followed in the book. It comes thanks to some Dwellers who almost entirely stay off the page of the book. Our protagonist's escapades have uncovered one piece of information, true; but that can't be used.

I haven't read Banks' Culture series, but I've heard that, in the background, everything the protagonists do isn't necessary, but just allowed by the super-AI's to let them feel helpful. Whether or not this's true about the Culture series (I haven't read it), that's something you want to keep very far in the background because if it ever becomes relevant, it's going to make your whole plot feel useless. This book fails to do that: for all the helpful-seeming things our protagonist is doing, the super-advanced Dwellers are the ones who actually solve the problem.

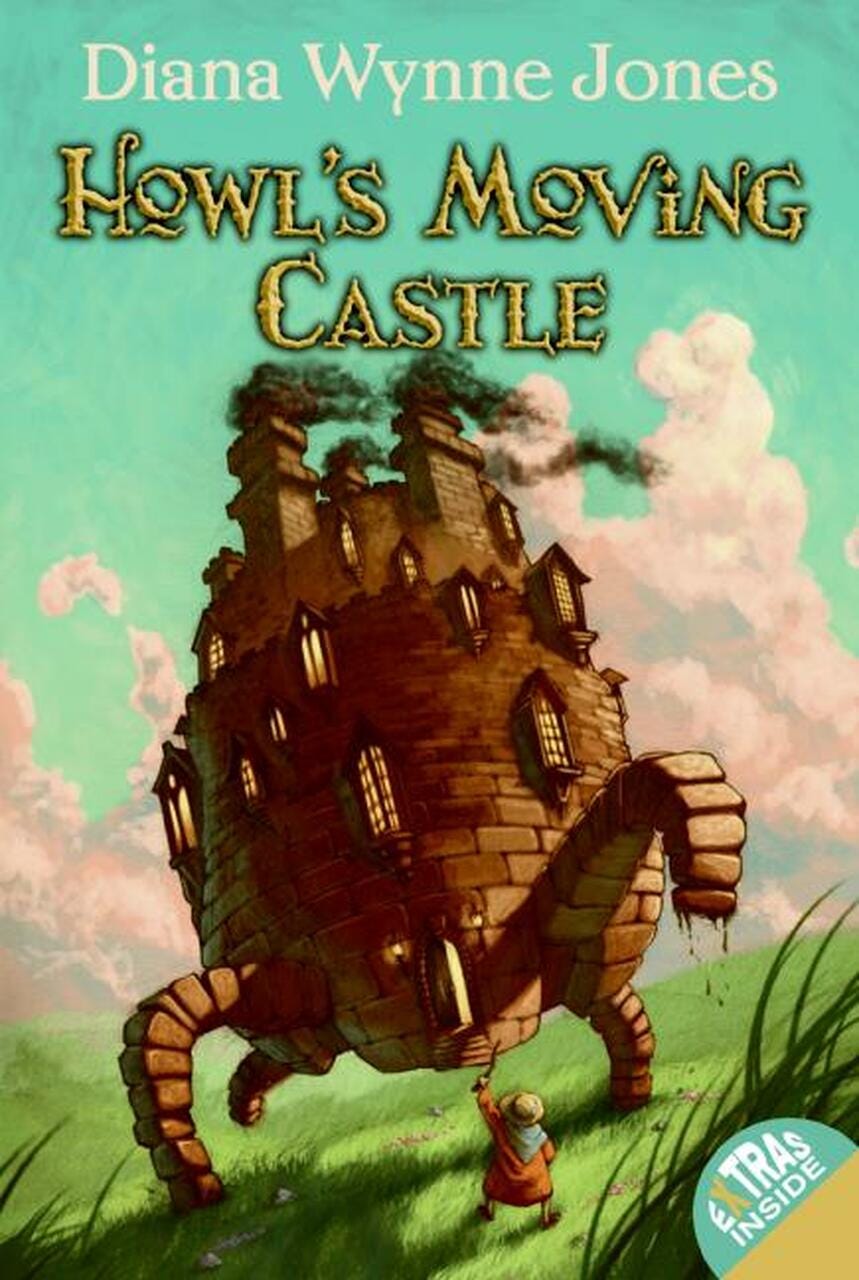

Howl's Moving Castle, by Diana Wynne Jones (329 pp; 1986)

Who should read this? People who like fun character-focused fantasy adventures.

I'd read this fun book as a teenager, enjoyed it then, realized on rereading it that I'd forgotten most of the story, and enjoyed it again now.

In a fairy-tale country, our orphaned protagonist feels that as the eldest of three sisters, she wouldn't be able to find her fortune - so she must stick around with her stepmother. But when she gets cursed by a witch, she goes off anyway and finds the infamous Wizard Howl... who proves to be not as horrible as rumored, reluctant to make decisions, and ready to put up with her as housekeeper for all his whining.

The rest of the book is their rough edges sparking off each other in a very well-done way, to great revelations of the mysteries in each other's backstories and of great character development for them both. There's a conflict with the evil Witch of the Waste, and negotiations where the king is trying to get Howl to help him fight that witch. But the real core of the story - both in feeling and page count - is the byplay between our protagonist Sophie and Howl.

Thanks! It's encouraging to find someone who actually reads

I've read two of Banks's Culture novels, and "disappointing and cynical" sums up how I felt after finishing each of them. It seems as if his characterization of the transhuman Minds consists entirely of their making snarky comments, and as if everything his human-level characters do is ultimately futile. I don't understand the appeal.