Luther and the Spark of the Reformation

This week in 1517, Martin Luther posted the Ninety-Five Theses

This week in 1517 - on October 31st, All Saints' Eve - Martin Luther posted the Ninety-Five Theses on the Wittenberg church door, in what has been deemed the start of the Protestant Reformation.

The Theses themselves weren't revolutionary, and Luther wasn't posting them as a manifesto. He wasn’t trying to raise a popular movement, much less found a new church structure. Luther, a professor at Wittenberg University, was posting them as theses he hoped to defend in debate, on what was effectively the university bulletin board. Their original title was "A Disputation Concerning the Value of Indulgences".

But, this did in fact lead to the Protestant Reformation. Luther would be hailed as the founder of what would be called the Lutheran Church (though he himself refused to call it that name and minimized his role), and more distantly of all Protestantism and of modern Europe.

The immediate thing that had prompted this was an indulgence-selling campaign by popular preacher Johan Tetzel.

If you're not precise, buying indulgences sound like you're buying forgiveness of your sins. That's technically not how Roman Catholics (then or now) say they work, but - then as now - people can easily end up thinking that. Technically, indulgences are remitting some of the penalties for sin that's already been forgiven and repented of. The Roman Catholic Church traditionally gives them out when people do some good deed, such as going on a pilgrimage, or saying prayers. On the other hand, giving money to the church is also a good deed... so it was all too easy for late-medieval bishops to turn this into a fundraising campaign. So, Luther saw Tetzel essentially selling indulgences: giving them in exchange for set sums of money.

(After the Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church stopped giving indulgences in exchange for specific gifts of money. Nowadays, they're offered for things like prayers; and the need for repentance is more emphasized. As a Protestant, I still think indulgences are a bad thing - but they're much less bad than they were.)

In Tetzel's case, some of that money went to building St. Peter's Basilica in Rome; some of it stayed with the local bishop. Also, to drive up traffic, Tetzel and other preachers played fast and loose with the technicalities and often didn’t mention the need for repentance. Luther was a pastor as well as a professor; he'd talked with many people who'd fixed their hope on indulgences.

So, when Luther wrote in his Theses that Jesus "willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance", and that "it is vain to trust in salvation by indulgence letters", he was speaking in line with official church doctrine, reining in what people would agree was a bad thing.

But Luther did differ from Roman Catholic doctrine, and that would soon become more evident.

Luther already believed that it's God alone who saves us from our sins, based solely on our faith. Our works - anything else we do - don't matter. He based this on the Bible, which he held as more important than anything else in defining doctrine.

When Luther had posted the Ninety-Five Theses, he had been looking for a debate. He got much debate - but debate against churchmen accusing him of heresy. And, his positions became more radical as the debate continued. A year and a half later, at Leipzig in 1519, Luther would be denying the authority of Popes and Councils; at Worms in 1521, Luther would be famously holding the Bible as his only authority:

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God.

This still remains foundational to Protestant doctrine today. Luther wasn't the first person to teach this - John Wycliffe in England, and Jan Hus in Czechia, had taught many similar things with some success. But it was Luther who sparked the explosion of the Reformation.

A year after the Ninety-Five Theses, in 1520, Luther was calling on the nobles and princes of Germany to reform the Church in their territories. Many of them would eventually take him up on that offer, leading eventually to established state churches. But Luther wasn't trying for that; he still wasn't trying to establish a separate church. There were myriads of precedents where medieval kings had tried to fight corruption in the church. Luther was merely extending that principle further.

But the Reformation did largely end the medieval concept of one unified international Church - a "Catholic Church," or "universal church" to translate the Greek. Luther always insisted that Protestants, or to use his preferred term "Evangelicals" ("Gospel people" to roughly translate the Greek) were still part of that catholic church. As a Protestant myself, I wholeheartedly agree. But that's a more tenuous and less visible sense than medieval Christians could point to.

Instead, Europe got wars of religion - the Schmalkaldic War, the Thirty Years' War, and more. In part, they were driven by other political reasons. Germany and Europe had frequent wars before, and many German nobles had adopted Protestantism due to already having political grievances with the Pope and Emperor. But religious differences made them much worse.

The wars of religion petered out with the maxim of "cuius regio, eius religio", where each country would set its own state religion. This ended up hurting both the state and the church, of course. People who disagreed on religion were forced into opposition to the state, and the church was forced to moderate its behavior at the behest of the state. Even today, we still have the British Parliament occasionally making laws for the Church of England. More soberly, many scholars have blamed the German churches' habits of following the state's leading for how they barely spoke up against the Nazis.

Luther didn't expect any of this. The part of it he did see, he was in many ways sorry about.

But another consequence of the Reformation was mass education. Driven by the importance of individual faith, Luther and his followers started actually reforming village churches throughout the Protestant territories of Germany. They found myriads of villagers and even priests who knew next to nothing of Christianity besides a few rote prayers. Superstitions and magical rituals ran rampant.

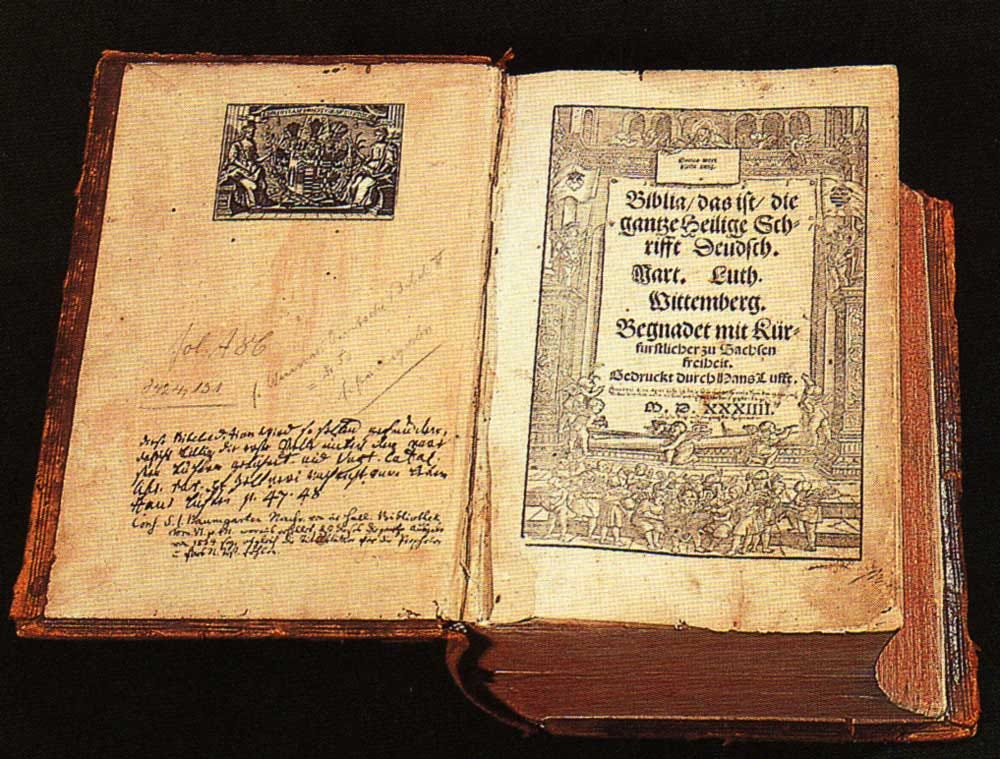

Luther replaced many of those priests, and started amending all of this by educating the people. After the Reformation, they had a Bible in their own language, public readings from it, and sermons expounding it. Roman Catholics, in response to the Reformation, took up this same program of sermons and (eventually) Bible translation.

Over time, spurred by this foundation, other education could build on this. When the Puritans of Massachusetts established public schools to teach every child to read and write, they explained it with the vital importance of reading the Bible - in words that Luther would have recognized and endorsed.

This part, Luther absolutely did intend.

When Luther posted the Ninety-Five Theses, he didn't mean to spark what he sparked. But he absolutely did hope to change the world. And - though not as he intended - it was changed.

Much of that change, Luther didn’t do himself. That was the main difference between Luther and previous would-be reformers, like Wycliffe, who had taught similarly. Events built around Luther, to build his Ninety-Five Theses into a movement. Luther himself recognized this, attributing it to God and God's Word:

I simply taught, preached, and wrote God’s Word; otherwise I did nothing. And while I slept, or drank Wittenberg beer with my friends Philip and Amsdorf, the Word so greatly weakened the papacy that no prince or emperor ever inflicted such losses upon it. I did nothing; the Word did everything.

I wasn't expecting a sermon in my in-box. I'm a Catholic-educated atheist. I recognize the Protestant Reformation as an historical turning point, but don't believe In Protestant dogma any more than I do the Catholic version. There's a tendency in Whiggish history to equate Protestantism with personal liberty, when figures such as Calvin and the Puritans in the US could be just as fatally nasty to those they considered heretics as the Catholics were. Check the Philadelphia Nativist Riots for a lesson on the wisdom of state education that takes sides among denominations.

> Luther already believed that it's God alone who saves us from our sins, based solely on our faith. Our works - anything else we do - don't matter. He based this on the Bible

And yet the bible also says that if someone really has faith it will be apparent in their works (James 2:18). So works do matter.

Also, as a practical point: what do is what you are and what you are is what you do.