In-Universe Metafiction

When the Book Exists Inside the Book

Sometimes, an author will create a fictional history for his novel.

This was very common in the earlier days of novels: authors would say they were the fictional diaries or collected correspondence of their narrators. Robinson Crusoe kept a journal on his desert island; Jonathan Harker and his fellow characters in Dracula apparently kept copies of their correspondence; presumably they were collected and published after their respective adventures. But some authors develop this metafictional history in much more detail.

Tolkien took this the farthest of anyone I know. He made up a full fictional history for his stories, and then made up a detailed fictional history for Lord of the Rings within that fictional history of his world. At the end of Lord of the Rings, shortly before leaving the Shire, we see Frodo give to Sam his book: titled "The Downfall of the Lord of the Rings and the Return of the King". The appendices describe how this book was then passed down by Sam's descendants as "The Red Book of Westmarch", and how a copy was given to Gondor and a few addenda made there. At some point, copyists apparently added marginal poetry (which we find in Tolkien's poetry collection The Adventures of Tom Bombadil). And then (we’re invited to guess) the Red Book of Westmarch made its way into the hands of the modern Professor Tolkien.

Of course, none of this actually happened. Tolkien was happy to detail in his letters how he actually invented the story of Lord of the Rings. But, this metafictional pretense - this history in which the book exists inside the universe of the story - adds fun and charming depth to the story.

When the book exists inside the world, you as the author can use it to change the characters and the world around them.

Tolkien mostly does this in anticipation. Throughout Lord of the Rings, the hobbits keep talking of past legends in the world, remark on how they're part of the same story, and occasionally even talk about how their story will appear when it's written down. The first draft showed this come to fruition in an epilogue where Sam was reading the book to his children and answering their questions. I read the epilogue, and though it needed some editing, I'm sorry it wasn't part of the final book. As it is, we're left with that a couple scenes like when Frodo gives Sam his book, and some scattered mentions in the appendices.

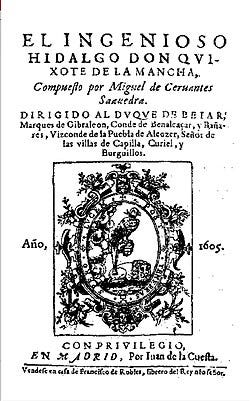

One of the best non-Tolkien examples of this I'm aware of is Don Quixote, which's been hailed as the first modern novel. Miguel de Cervantes, the author, attributes the text to a nonexistent fictional Moorish author named Cide Hamete Benengeli. More specifically, Cervantes says that - inside the world of the story - Benengeli wrote and published Book One of Don Quixote in time for people to have read it before Book Two happens. In Book Two, we see Don Quixote and Sancho Panza embarrassed by their sudden fame from the success of Benengeli's Book One, and we see other characters now immediately familiar with them from having read it.

Cervantes doesn't construct an elaborate in-universe history for this; we don't know anything about Benengeli. He has no personal presence in the story besides referring to himself in the narrative a few times, and as far as I'm aware, Cervantes didn't leave us any clues to him in the text. But he hugely succeeds in using the existence of the book in the story - perhaps even more so than Tolkien did.

I can think of two more recent authors who tried this at some length, but neither does it as well as Cervantes or Tolkien.

For example, the Animorphs young-adult series, by K. A. Applegate, purports to be the secret diaries of the teenage protagonists, written during their secret war against invading mind-controlling aliens. In the last book, set after the war, we get a brief mention of their autobiographies having been published. However, this makes no sense in-universe. They start out each book by explaining that, for secrecy, they aren't giving their full names or their town's name. This makes sense during the war, given their (understandable) often-repeated concern for secrecy. But then, why would they write such revealing diaries in the first place? And if they were published after the war, would they not have been edited then? This makes total sense if optimizing for real-world readers, but at the expense of in-universe sense.

For another example, C. S. Lewis (a friend of Tolkien's) spelled out a short in-universe history for his "Space Trilogy" at the end of the first book, Out of the Silent Planet. After the protagonist Ransom returns to Earth, he and his friend (then-unnamed, and so far not part of the narrative) notice some signs that extraterrestrial powers have been meddling in Earth in the past. So, they decide to publish Ransom's story - as fiction, because it'd otherwise be unbelievable. This guise is continued during the second book, Perelandra, where Ransom's friend is explicitly named as "Lewis," but it's worn somewhat thin by then. Lewis entirely abandons it in the third book, which makes sense given that he tells it from a completely different limited-third-person perspective.

In both of these, the pretense of an in-universe metafictional history wears thin. We don't know why it would be written inside the universe, and it isn't integrated into the universe.

That said, it's hard to do this well. Even Tolkien failed when he tried to give a deep metafictional narrative to his Silmarillion, because he didn't settle on or develop clearly who wrote it.

In the very earliest drafts of Silmarillion (published posthumously in History of Middle-Earth volumes 1 and 2), the metafictional history was clear: this was written by Aelfwine of ancient England, a human mariner who'd sailed to Tol Eressea and heard the tales there. For all the faults of this early draft, we knew who was narrating it, and Aelfwine gave it a relatable perspective.

But then, Tolkien deleted Aelfwine and decided the book would be written by an elf named Pengolodh from Gondolin. We never see Pengolodh; Tolkien only wrote brief mentions of him. One blogger went to some effort to guess at Pengolodh's character from the published Silmarillion and his choices of perspective and narrative asides; I enjoyed reading that, but next to nobody actually reading the book is going to get any of that. I'm not even sure how much of that was intentional on Tolkien's part.

Choosing the right narrator can make or break your book, and if you're setting up an in-universe metafictional history of your book, that implicitly sets up your narrator too. We know the narrators and in-universe authors of Lord of the Rings and Animorphs; having them write and narrate their respective books rewards us with so many more gems about the characters we know and love. Lewis does this very well in another book of his, Till We Have Faces, which is written in-universe by his protagonist, Orual, in two parts. She writes Part One, recounting her life so far, as a complaint against the gods; she writes Part Two, describing her subsequent life, to tell the gods' answer to her complaint. In both sections, her perspective shines through every word and makes the book and her character so much richer.

But in the end, we know little of the "Lewis" inside the story of the "Space Trilogy," less of Pengolodh of Silmarillion, and even less of Benengeli from Don Quixote. This makes their books suffer. If they'd wanted to strengthen this, they would have done better to choose more familiar characters. Tolkien, as blogger Tom Simon points out, even had a loved character easily available to narrate Silmarillion. Bilbo could have been its in-universe author, and he would have made Silmarillion much more charming and more relatable to readers.

I'm not blaming authors who don't construct a full in-universe history for their novel. It's a difficult task. This goes several steps beyond having the narrator be a character, which - as I mentioned in that post - few authors try anymore these days. It demands building out your characters and the structure of your universe more, so that you can think how the characters would react to their own story. Tolkien and Cervantes did this well, in very different ways. But then, Tolkien fell flat - after decades of tinkering - when he tried to do it again later in his life on a larger scale.

But when it's done well, it can make the book so much richer and more fun to read. And I can guess from my own small attempts at telling stories, it's also fun to write.

Besides Tolkien, I think David Brin's uplift series might be my favorite world building. Again thanks for writing.