Last March 20th, Vernor Vinge - my favorite hard science fiction author of the modern era - died.

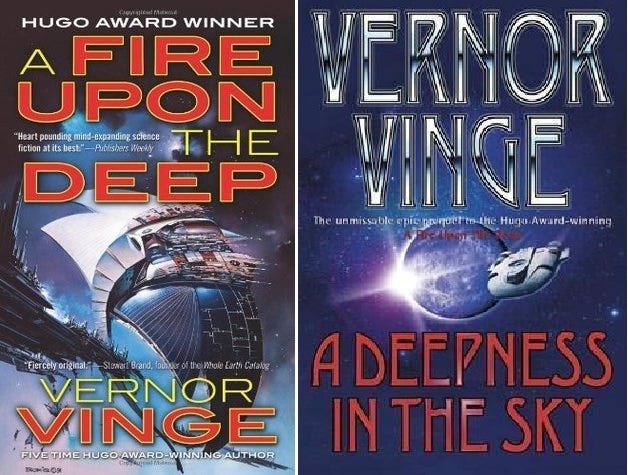

I first encountered Vinge's books in college, when I saw his novel Fire Upon the Deep recommended online as one of the best novels about the Singularity. I'll talk more about what that means below, but in short, I agree with that evaluation. What's more, it was a fun, exciting, and deep novel.

I continued through several more good books of his (A Deepness in the Sky, The Peace War, Marooned in Realtime, and The Witling), and then stopped at some others (Tatja Grimm's World and Rainbow's End) that weren't so good. He had his weaker stories, but when he wrote well, he wrote very well.

Unfortunately, he also wrote slowly: only two of his novels were published after 2000 (Children of the Sky and Rainbow's End). He reportedly had plans for a fourth novel in the universe of Fire Upon the Deep, Deepness in the Sky, and Children of the Sky, following up on the tantalizing sequel-hooks he’d left; but unless his heirs find a surprise among his papers, it'll remain forever unwritten.

Vinge wrote hard science fiction.

Traditionally, the definition of hard science fiction is - as Wikipedia puts it - "concern for scientific accuracy and logic." Both points matter here. Like most hard sci-fi, Vinge's work included things that aren't scientifically accurate, like faster-than-light stardrives. In fact, he went well beyond that to include things like teleportation (in The Witling), time-stopping bubbles (in Marooned in Realtime), and different physical laws in different zones of the galaxy for ill-explained reasons (in Fire Upon the Deep).

But what makes me love Vinge's books is that he treats these things rigorously once they exist. The time-stopping bubbles yield societies built around one-way time travel, the teleportation yields all sorts of practices built around how it preserves momentum, and exploiting the different zones of the galaxy gives rise to the whole plot of the novel. Vinge always explains what is needed for the plot, and adds some properties or limitations which leave me nodding. Of course (I think) this's how bubbles, or teleportation, would interact with known scientific laws. It rhymes. And then, that's carried through rigorously for the rest of the book.

Hardness isn't the only way for science fiction to be good; you can tell a good story without it, and sometimes the less-plausible elements help the story. Witness, for example, Star Trek - or to take a couple other examples I noticed on my bookshelf just now, Scalzi's Lock In or Wright's Golden Oecumene trilogy. But Vinge builds his plot around the hardness, which gives it another level of intellectual beauty.

The one thing Vinge doesn't explain is where the inexplicability is the point.

I'm referring, of course, to "The Singularity." At some point, the theory goes, technology and intelligence will start increasing so quickly that, as it builds upon itself, it'll yield things completely unpredictable and somewhat incomprehensible from what happens before. It would be something like the Industrial Revolution sped up: 1940's society and technology would totally shock someone from the 1740's, even someone familiar with social and technological trends. But beyond that, in the Singularity, technology will build technology using increasingly-intelligent AI's. As one character in Vinge's Marooned in Realtime puts it, at the start of the Singularity, he'd leave Earth for a week and come back to a culture and economy totally different because things had been changing that quickly.

Vinge believed this would really happen. In fact, he was among the first to popularize the concept. Specifically, he wrote in 1993 that the Singularity would happen thanks to building superintelligent AI, and "I'll be surprised if this event occurs before 2005 or after 2030." Twenty years of his window have elapsed so far, but it hasn't closed yet. Given recent AI progress, I wouldn't be surprised if he stood by his prediction toward the end of his life.

Besides all the challenges that would go with its actually happening, the Singularity is a challenge to novelists. How is one supposed to write stories set after the Singularity and make them comprehensible and believable to pre-Singularity human readers? It's a frequent problem. Most writers avoid it by avoiding the Singularity. For example, in Star Trek, computers are extremely limited, and robots (such as Data and the Emergency Medical Hologram) are humanlike. Even the superpowerful non-material Q turn out to have humanlike minds.

Vinge avoids this. Instead, he often has the Singularity happen - but he sets the story at its margins. In A Fire Upon the Deep, the zones with different physical laws make sure superintelligences can only happen at the edges of the galaxy. Of course, they can still influence events elsewhere - that's the whole plot of the book - but the events are happening on a more human scale. Or, in Marooned in Realtime, once the Singularity has happened, humanity (or what it's become) vanishes - leaving behind the people who were in the time-stopping bubbles at the time. The plot is set around those people who've missed the Singularity.

But on top of this, Vinge also just wrote good books.

His characters include amazingly alien aliens who gain our sympathy as good characters.

In A Fire Upon the Deep, we see sessile aliens symbiotic with technology, and aliens where one self-identity and mind is shared among many bodies. These short descriptions don't do justice to their strangeness. We see more of that over the story. Vinge carefully works through and shows us the implications of these aliens' different natures, just like he does his technology.

Then, in A Deepness in the Sky, it seems at the beginning that Vinge is writing humanlike aliens (in their minds, though not in their bodies). But - in a beautiful twist - we learn the narrator is untrustworthy and they're actually much stranger than we've been seeing.

But in both cases, amid their strangeness, we see them as sympathetic, engaging people.

I haven't even talked about how Vinge keeps building twists and surprises into his plots. It's hard to talk about that, because I don't want to spoil those surprises.

To vaguely gesture towards a few examples, the nature of the bubbles in The Peace War is discovered midway through the plot, as are some of the machinations of the evil AI in A Fire Upon the Deep. Both of these make perfect sense in retrospect, but they were huge surprises to me when I was reading the books, as a good twist should.

Vinge was a very good writer in how he wrote his books, and also (when he was his best) a very good worldbuilder and plot designer. I'm sorry he didn't write more, though his day job as a computer science professor (before retiring in 2000) rendered that perfectly understandable.

And I was also very sorry to hear that he died. May his writing continue to entertain and inspire many.

I thought Rainbows End was quite a good novel. The scene where Alice Gu falls victim to JITT as a result of an arcane biological attack, and explains the whole situation, but in language that no one else can understand, strikes me as brilliant every time I read it. And the whole book manages the same kind of long sustained climax that Vinge achieves in A Deepness in the Sky, something he did better than any other writer I've encountered.

On the whole, though, I think I would have to pick A Deepness in the Sky as his single greatest literary achievement. Among other things, he managed to come up with a newly imagined form of totalitarianism, one dependent on technology beyond anything we're capable of—and rather than putting it into a grim dystopia, he showed an ongoing struggle between the totalitarians and the much more libertarian Qeng Ho. (That novel won his second Prometheus Award.) I have to say that, having worked for a large corporation, I found a grim irony in the Emergents' concept of "human resources."

Thanks very good assessment of VV. I think the short story True Names 1981 deserves a mention as an amazingly prescient founding text of cyberpunk.