How It Allegorically Happened

Historical Fiction Films

How It Allegorically Happened

I've watched a couple of interesting historical-fiction movies recently.

On the one hand, they weren't history. They weren't literally true, or anywhere near literally true. It's almost a proverb that film adaptations of books are usually worse than the book, and I'm inclined to agree in most cases. Film adaptations of a book I like can hardly ever catch all the good parts of the book. Similarly, film adaptations of history - judged by the standards of history - can't catch the details of history.

But, they can tell their own stories - and tell them very well. What's more, even though not literally true, they can be allegorically true. They don't show exactly what happened, but they tell the same story as history - in a different way, in a different sense. They aren't literally true, but they represent what literally happened by giving us something similar that hits us with the right feeling.

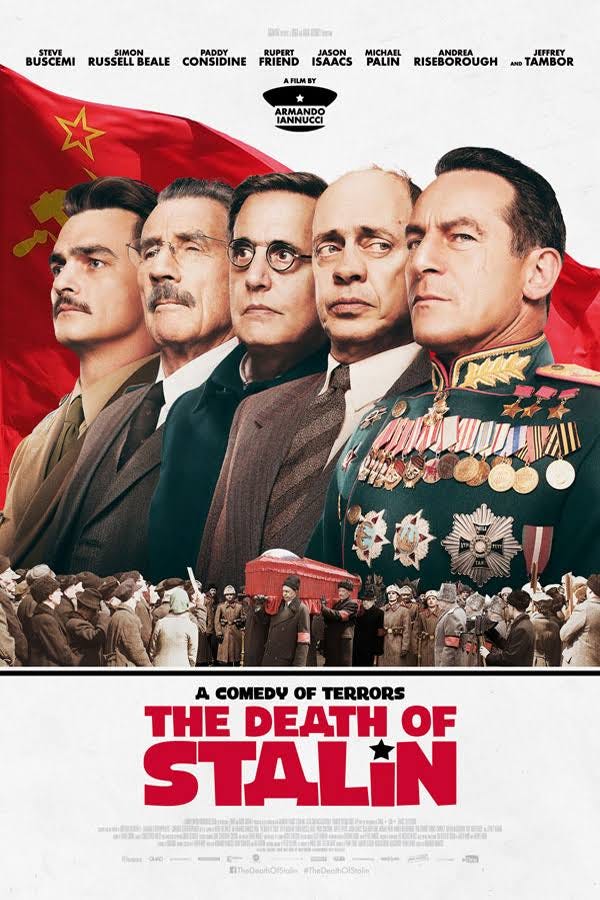

So, some weeks ago, I watched The Death of Stalin (2017). It's a good story. "Dark comedy," they call it, and it is, and the USSR is a perfect setting for this dark comedy - from watching the symphony running around to arrange a perfect recording for Stalin, through the Politburo stumbling and blaming each other while literally carrying Stalin's coffin.

There're historical inaccuracies; there're characters whose historical personalities have been replaced for the sake of the plot. For a few examples of many, Molotov and Zhukov weren't actually in the high positions they bear in the film, and Molotov's actual personality was very little like how he's shown. But, it all fits. There were people acting like how Molotov is shown; they need to be represented in the story. The whole story at the beginning of the film where Stalin asks for a recording of the concert, and Radio Moscow immediately re-stages it to get a recording, probably never happened - it's only recounted in one unreliable source. But it graphically shows us how the whole Soviet system was built around giving in to every one of Stalin's whims. If not literally how the death of Stalin happened, this is symbolically and allegorically how it happened.

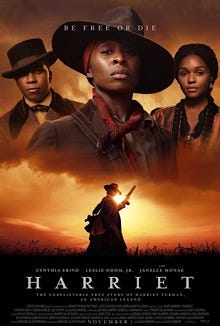

I also recently watched Harriet (2019), a biographical drama about Harriet Tubman. It's a very differently-framed tale, telling the story of Tubman's life - not all of it, but most of it: her escape from slavery and her work leading other slaves to escape on the Underground Railroad. Of course, it has a very different tone than Death of Stalin, and focuses on one person over a longer time rather than several people around one pivotal stretch of time. However, I noticed that it's like Death of Stalin in one sense: at several points - especially toward the end - it too tells not how things literally happened but the story of how they symbolically and allegorically happened.

At the start, from my knowledge of the history, the film gets myriads of details correct. However, after Tubman's first successful trip back, the film quickly fast-forwards through several other trips to show a continuing conflict with her old master. As far as I know, the physical confrontations and climax they show didn't happen, nor are they an extrapolation from something that did. Tubman did go back for her parents and family - multiple times - but not so dramatically as shown here. However, just like in The Death of Stalin, the symbolism fits beautifully. Everything symbolizes something that did happen, down to Tubman's film character prophesying the impending Civil War.

(And there're other beautiful parts too, like the gospel music in the soundtrack. For that matter, the classical music in Death of Stalin was also great.)

Historian Richard Overy has criticized The Death of Stalin saying that Stalin's victims "deserve a film that treats their history with greater discretion and historical understanding." This film, he accuses, both gets the details of history wrong and "ham[s] up the story for laughs." He's not totally wrong; the victims do deserve their full story to be told. Of course that's impossible; history is fractally deep; even aside from the inevitable gaps in history, no one's full story can be told with human words. But given that, they deserve their true story to be told in great detail.

But on top of that, they deserve something people will watch or read, grasp, and understand. The details of their story are already available in myriads of books; I've read a few bits of them (and of escaped slaves' stories). But I've only read a few bits, and most people won't even read those. (This isn't a new thing, as we can see from the medieval saints' legends, Arthurian romances, and tales about Alexander the Great building a great wall against the northern barbarians.) "Never forget," people proverbially say about another atrocity, the Holocaust; but remembering only a brief sterile summary is already partway down the road to forgetting. They also deserve to be more remembered - to have some part of their story be told as something that people will watch and understand.

And for all its black comedy, Death of Stalin does tell one important part of their story. It pulls out of history the bizarre ludicrousness of Stalin's personality cult and tells it in a way people will remember. Similarly, Harriet pulls out several important threads of Harriet Tubman's story. Where they're not literally true to history, they're allegorically true in that they follow those threads. If what they said didn't happen, something like it happened. Even though these movies do tell some wrong details, they get the overall arc of the story correct.

We see this with the reaction to the play Hamilton. It pulled on several threads of Alexander Hamilton's life, and it revitalized public interest in him to the point that there was a popular campaign to keep him on the ten-dollar bill. In theory, if Chernow's biography of Hamilton (the inspiration for the play, a very comprehensive biography) had become as popular as the play itself, it would've taught people even more about Hamilton; in that very different world, people would've gotten both the arc of the story and the details. But in this world, it wasn't going to become that popular. Just like in these two movies I watched recently, the playwright's picking several threads, and spinning and developing them, is what made it possible to become popular and for people to learn what (allegorically) happened.

Of course, this depends on the skill of the scriptwriter.

Even in the Harriet film, I was disappointed when we saw once - explicitly calling themselves by that name - a meeting of the leadership committee of the Underground Railroad. In actual history, it didn't have any organized leadership; Levi Coffin was called "President of the Underground Railroad" but that was a completely unofficial title given from people's esteem for him. I think this's an important point in the story - not necessarily in the threads they pull on for Harriet, but I'm sorry that they worsen people's understanding of the Underground Railroad in this one way.

In worse stories, this can be distorted even worse. I can't think of a film to cite here, but consider Bernard Shaw's play St. Joan. Joan of Arc is interpreted as convincing people to go along with her by the force of her personality, she preaches a nationalistic conception of France, the military victories just happen, and she's burnt thanks to misogyny and the clerics supporting an internationalist conception of Christendom (which Shaw viewed as dull next to nationalism). These elements were present or at least implicitly latent in Joan's life, but in exaggerating them, the play minimizes so much else - such as, most centrally, her religion and her claims to be hearing voices from Heaven. If you miss that point, I can't say you've understood Joan's story.

This shows up sometimes in books too. Analogous to these plays, the Mutiny on the Bounty historical fiction trilogy does it fairly well: the authors freely rearrange minor events to tell the story of the mutiny in an engaging way (with, in the first volume, an invented protagonist.) However, I think it's more frequent in films and plays. Historical fiction books - or at least, the historical fiction books I've read - usually try to tell a story invented by the author woven around the historical events with invented or largely-invented protagonists, and they have more space to explain the details of history. Films and plays have less space for invented events and protagonists; they often try to tell an actual storyline of history and have to compress it.

When I see a story allegorically telling how history happened, I'm glad. I know that the storyteller doesn't just see history as a sequence of events and dates, but as a story. The events have meaning; threads can be traced; events can therefore be allegorized. Perfect history might be better than imperfect history. But, all history is imperfect, and even a not-inaccurate list of events is nowhere near perfect because it's missing most of what brings life to the story.

So I'm glad I watched these movies. A documentary would've been literally more true, but it would've rung fake to the feelings. These films told - if not literally how it happened - then allegorically how it happened.

May there be more like them.