I already wrote one whole post about Asimov's short stories about robots, but something else struck me when I was rereading them last year. These short stories were written over years, but when they're placed together in one set of covers, they feel like they tell one overall story.

This struck me because I'd just finished rereading another series of sci-fi short stories - Venus Equilateral by George O. Smith - which felt even more clearly like one story, halfway to being a novel rather than just a sequence of short stories. Unlike Asmov's robot stories, Smith's stories do share enough common elements to be a novel: they have the same location (the Venus Equilateral space station) and protagonists (the station's engineers) and often recurring villains. But, each story could indeed stand by itself - and they were originally published separately. They were only collected in one book long after the fact.

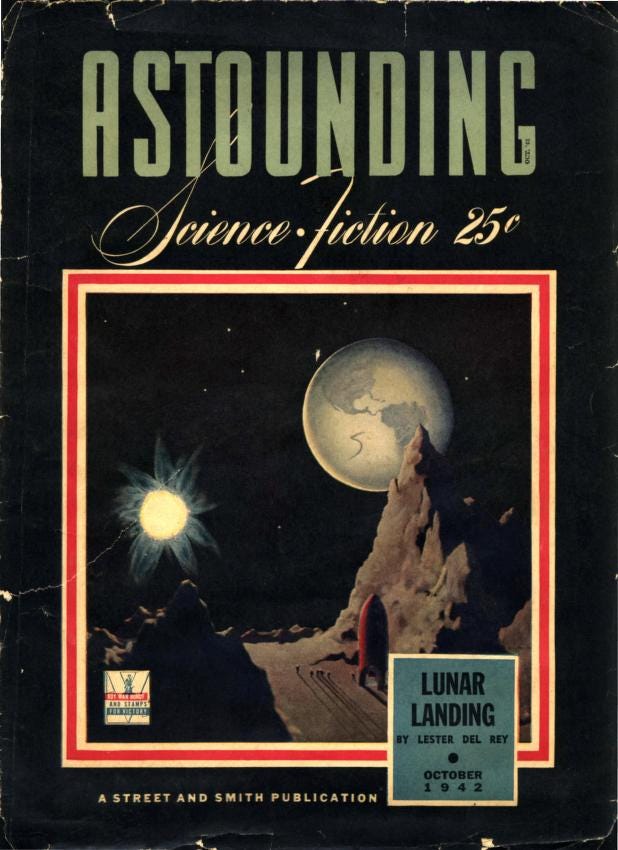

This's formally called a "fix-up," and it used to actually be relatively common. In Asimov's Foundation saga, the first couple books were compendiums of novellas originally published separately, set generations apart. Even Haldeman's The Forever War was originally published (in 1974) serially. It's not so common anymore, with the short story market having largely evaporated - and I think that changed the nature of stories being told.

What Asimov and Smith both do is set the stories in a clear thematic progression. For Smith, his protagonists are inventing more and more things - communication to ships in space; a new power generator; a matter duplicator - that change the face of the solar system more and more. For Asimov, we see the invention of hyperdrive, and robots gradually changing the face of Earth even as normal robots are feared by the normal person.

Then, of course, we have continuing characters. Smith has this much more; most of his characters continue across stories. We learn to love our protagonists and cheer Channing and Arden's romance and marriage; we cheer as they repeatedly defeat the increasingly-enraged villain. Asimov has many fewer returning characters, but we still have fun tracking the returning careers of Stephen Byerley and Susan Calvin.

Both these points are, of course, the same things a good novel would do. But I think they have different value in a set of short stories where we wouldn't necessarily expect to see them; and also a different value when we see them behind the different stories' own plot arcs.

Because, in both cases, the stories have their own plot arcs as short stories.

In fact, neither of these series were written as series to start with. It was the same way with Asimov's Foundation, Bradbury's Martian Chronicles, and so many more - they were first written as short stories, reusing setting and characters for convenience. Science fiction magazines were much more popular then than now; short stories were more convenient than novels to publish. It only happened later that the authors decided to tie them together more firmly with an overall plot arc.

Of course, many other authors have done this much - written many short stories in the same universe. For one example of many, take Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories. But, they have no unified plot arc. The individual stories don't tie together in any way except being about Holmes and Watson. Even the character of Moriarty - Holmes' nemesis in the popular mindset - only shows up in one single short story, and one later novel. Doyle wasn't trying to write an arc.

I don't know why Smith and Asimov started tying their stories together, but I think it was because they started liking their characters and wanted to continue their arcs. Asimov said that Susan Calvin essentially stole his robot stories as a continuing protagonist.

Regardless, I like the effect we get with both the short-scale and large-scale arcs.

This does handicap some things versus a novel. Most plot arcs must be concluded within a single story - or at least enough of the plot arcs to give a good resolution to the story. All the tie-rods of your overall arcs must be justified when they first appear.

In most Venus Equilateral stories, the villain looks to be defeated, even if he stages a comeback in the next story. Don Channing and Arden Westland might not be married yet, but their romance reaches a new milestone. Each story stands on its own. Even "Pandora's Millions," which interrupts the pattern to show us vignettes from across the solar system about how the recently-invented duplicator has disrupted things, still has a plot of its own.

Asimov makes his robot stories stand even more separately. In several of Asimov's stories, we follow the progress of the hyperdrive. It isn't built yet at the end of most of the stories, but the individual mystery they're facing is solved - and that mystery is by far the main focus of the story; the hyperdrive is merely background setting. The stories were originally published separately, and must stand separately even as they also stand together.

I've tried writing arcs of short stories myself; every time, I've failed.

I think my problem was that I thought of them too much as arcs. I didn't think enough about making the individual stories good as stories in their own rights, so I ended up with scattered scenes from a half-baked novel. I'm not planning to come back to them until either I can plot out a novel, or I want to write an individual story there.

Both Asimov and Smith did start with individual stories, and it shows. Asimov's earlier robot stories barely even fit into his larger arc. Smith's earliest Venus Equilateral story tells the story of their fight against unreasonable corporate management, which never shows up again in the entire arc. As things moved on, they did arrange things more intentionally - but they still focused on the stories. Smith's grand finale was written specifically for the collection, rather than being published serially like the others. Asimov tells two endings, one of which ("The Bicentennial Man") is only an ending thematically rather than closing off any plot arcs - and the original I, Robot collection ended several stories earlier, which also works as an ending.

So, the way to tell a good arc of short stories is to, first and foremost, tell them as short stories.

And that's hard. It's harder to write a good arc of short stories than just a set of short stories, or a novel.

If I consider either Venus Equilateral or The Complete Robot or The Martian Chronicles as a novel, they'd have serious flaws: arcs not followed up on, characters dropped, and plot points not properly led up to. The one exception I can think of is Foundation, where the sections are novellas not short stories, and the overall plot arc is about large-scale sweeps of history. I'm sure it's possible to write a short story arc that would be a good novel, but it's very hard.

Unfortunately, I don't think it's going to happen anymore. Science fiction magazines have declined, and the short story market has largely evaporated except for self-published stories online. New authors are being advised to start with novels or even series, because that's what can sell. The arc of short stories has largely vanished, because the short story has largely vanished.

But, I can also think of novels that fail on the small-scale level, where individual chapters are too slowly paced and don't advance any plot. Short story arcs avoid that flaw, because each story needs to stand on its own.

And that's why I keep thinking of short story arcs. They're a challenge, which avoids one potential failure - and when they're done well, it's really fun to see.

Thanks for this. I hadn't read any George O. Smith, so that was a treat. (His whole collection of short stories was ~$3 on my kindle.) The stories remind me most of Charles Sheffield's McAndrew tales. Which got me thinking of other short stories in the same universe/ setting. Clarke's, "Tales of the White Hart." I'm not sure that these were written/ published separately. Which lead me to think of "Callahan's Crosstime Saloon" Just a wonderful series, especially if you are a fan of puns. And then you have all the Heinlein shorts in his future history timeline. And one can not leave out Niven and his tales of known space, how can one not like Louis Wu. But when I think of my favorite Sci Fi Short story author, Theodore Sturgeon, alas I can think of no arcing stories. Unless they were all in the same universe which is our own?

Thanks again.

It seems to me that there's a difference between the Foundation books, which can somewhat plausibly be read as a series of novels, and I, Robot, which really can't be read as a novel. I'm not sure what it is that makes this so.