Cross-Country Cutscenes and Dramatic Unity

Last weekend, I was watching the Lord of the Rings movies with some friends. I'd watched them before, and of course I was very familiar with the story from the books, so this time I ended up noticing more some of the details and how Peter Jackson constructed the story for the screen. One of the biggest things I noticed was how he plays fast and loose with chronology and travel time to juxtapose characters in different locations.

For example, in Fellowship of the Ring, while the Fellowship is struggling through the magical snowstorm on Caradhras, the scene alternates between them in the snowstorm and Saruman (far away in Isengard) causing the snowstorm. This scene is plausible, because he's a wizard (with a palantir, what's more!) and can see them far off by magic. The same is true with the beautiful scenes of Sauron's magical gaze reacting to different characters.

It's a good way to show things, it's fun for the viewer, and it's a fun twist on an old and well-known storytelling concept.

But Jackson does the same thing in less plausible cases. For instance, in the leadup to the Siege of Gondor, we cut immediately from Faramir leaving the city gates to his going into battle a day's ride away. As historian Bret Devereaux says, "Tolkien’s plausible timetable gets mangled into something that makes little sense."

But, like Devereaux, I can totally see why Jackson does this. It's dramatic to see one group of characters make a move, and another group immediately respond - such as Aragorn leading the army out of Minas Tirith, and Sauron immediately emptying Mordor in the next scene, clearing the path for Frodo and Sam get to Mount Doom. Or, Gandalf and Pippin light the beacons, causing Theoden to gather the army of Rohan and immediately set out. Or, Theoden is riding for Helm's Deep, and Saruman sends out warg-riders to intercept him. The "emotional beats" (in Devereaux' terms) are magnificent.

In reality, each of these would take days. In the books, Gandalf urged Theoden to start mustering the riders to help Minas Tirith even before Helm's Deep, and Theoden still leaves before everyone's come. We don't know how long it took for Sauron to send messengers to his orcs - in theory, he's one of the very few people who could use magic instant communication. He could notice Aragorn immediately through the palantir, and send flying Nazgul around the orcs. But still, full camps of orcs would realistically take several days to move.

But these are things that people don't immediately think of, and they detract from the story. In the book, we don't see what Sauron and Saruman are thinking. We spend pages with Denethor and Theoden lamenting the lack of news from other people. In the film, with a narrative already compressed, we don't have minutes to spend on that.

What Peter Jackson is trying to do here is building what Renaissance dramatists (inspired by Aristotle) called the "dramatic unities": a story should be about one principle action, at one time, in one place. He didn't literally mean one location and day, but that whatever locations and times were in the story should be linked together:

"A poetic imitation, then, ought to be unified in the same way as a single imitation in any other mimetic field, by having a single object: since the plot is an imitation of an action, the latter ought to be both unified and complete..."

By compressing the chronology and showing action and response right after each other, Jackson is emphasizing these unities. The action is building on each other up to one climax, the time is in quick succession, and the place - well, by showing action and response across Middle-Earth, Jackson is showing all of Middle-Earth as one "place."

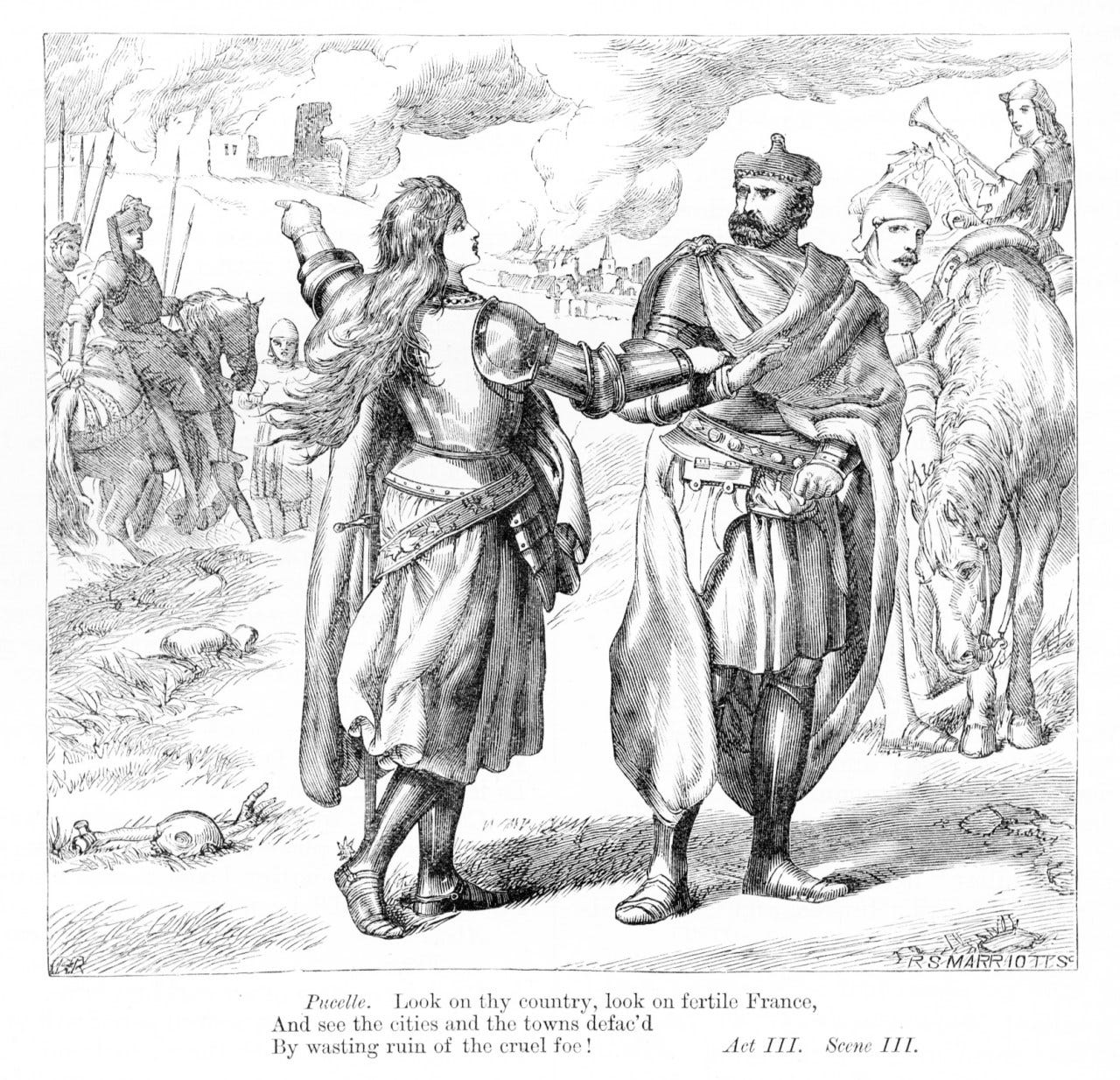

Shakespeare often did the same thing to some extent. In his tragedies and history plays, we're sometimes alternating between giving time to both sides of a conflict or war, like in Julius Caesar. But even when we're following one protagonist, we often have short scenes repeatedly showing us the enemies he's fighting - such as Macduff in Macbeth, or Joan of Arc in Henry VI Part 1.

These scenes serve much the same purpose in Shakespeare as in Jackson: to show them responding to our protagonists' latest actions, show what they're doing that the protagonist will be responding to next, and generally build tension. Shakespeare didn't show the responses in as much minute-to-minute detail as Jackson, but he's doing the same essential thing. It works for Shakespeare; it works for Jackson too.

I've been talking about Jackson so far - because this doesn't happen so much in Tolkien's original books.

Why didn't Tolkien do this? One reason is, he cared a lot about who was narrating the story and tried to minimize scenes where hobbits weren't present. But on top of that, my guess is, it's because he cared a lot about details of chronology, travel time, and geography. An author who made sure the moon rose at the same time for characters chapters and miles apart, and kept a day-by-day log of everyone's journey, would make sure that Saruman's army traveled at a reasonable pace. I'm sure he did care about this, but he wanted to keep it plausible in universe.

I think this's close to the same reason Shakespeare didn't do it as much as Jackson. For all his infamous reference to the "seacoast of Bohemia", Shakespeare knew viscerally that geography existed. If he sent a letter between London and Stratford, he knew that it took days to get a response. When he traveled between towns himself, he knew that it took a while and a great bother and frequently brought surprising news when he got to his destination. His audience would have the same visceral knowledge from living in a world without motor vehicles or telephones.

Most of us today, on the other hand, don't have that same immediate sense. Our history books need to point out that it took weeks (for instance) for news of the treaty ending the War of 1812 to get to America. Plausible worldbuilding can feel implausible or weird to the modern reader who isn't familiar with premodern conditions.

It's been said that there are two main plots to literature: "you go on a journey, or the stranger comes to town". In other words, you were to get new characters in one location.

When the nature of the story means you can't get them physically in one location, we can see that good storytellers try to show them interacting anyway as if they're in one location. It's more complicated, often more clumsy, and sometimes stretches probability. I can see why John Gardner advised young writers to try simpler plots where characters were in one place.

But - whether Shakespeare in Macbeth or Jackson in Lord of the Rings - it can be done. When it's done well, it's fun to watch. And regardless of how well it's done, it helps us understand one part of what makes a story.