Constraints as the Writer's Friend

Constraints on the story can be a challenge, but they can make it better

I've tried to write novels. I haven't finished any of them - I set down my latest to start this blog - but I've gotten an inside view of at least part of that creative process. One thing I know very well is that while the author's first idea might carry a solid core of the story, a lot of the shape comes later.

What's more, many of the most interesting ideas can come from constraints. I know that was the case in the storyline my sister and I developed together in our childhood: some of the most interesting plothooks came from backstory elements we refused to retcon, or from characters that we realized wouldn't stay out of a specific plot arc. I've seen the same thing in the novels I've tried to write, which convinced me it's the case for other writers too.

A lot of the time, we can't know about this, because the author went through it privately. From reading the published book, we might be able to guess what decisions the author made and where he was working under constraint, but those would just be guesses. C. S. Lewis once said that no literary critic had ever guessed right about his own writing process. Robert Heinlein said that, years after he revealed that Starship Troopers had been written in two sections years removed from each other, no critic had ever guessed when he'd left off.

But sometimes, the author has told us about the process. And that - in addition to my own experience - tells me that constraints can often spur creativity.

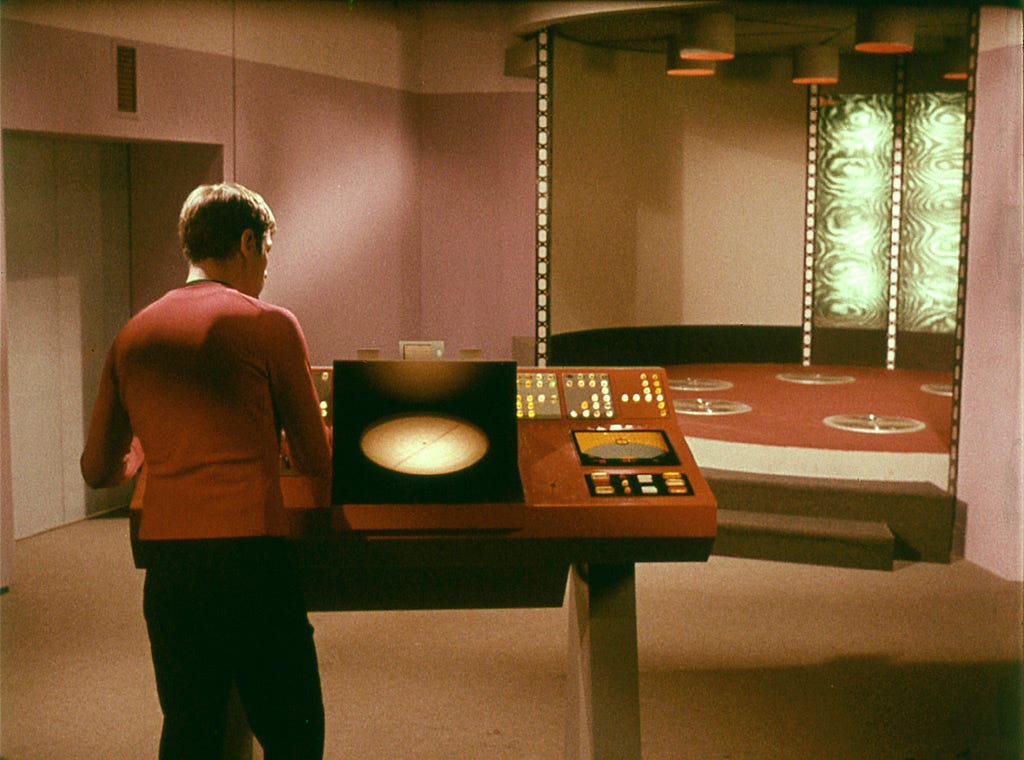

For a simple example, take Star Trek. Originally, the show's creators were planning to simply have the starship Enterprise send shuttles down to each planet. However, the shuttlecraft models weren't ready in time to film the first episode, and besides, it was looking like it would be too expensive to have a shuttlecraft scene in each episode. Spurred by this, they invented the idea of the Transporter.

This decision gave rise to what could be one of the most memorable aspects of Star Trek. While it's not at the core of the Star Trek story per se, it helps most of the episodes' individual stories work smoothly. It speeds up the action, both on camera (where we'd otherwise need some shuttlecraft shots) and in-universe (where we'd otherwise know the characters were spending an hour or so resting in the shuttlecraft between scenes.) This helps keep tension high and sequencing of events simpler; characters can even be beamed directly out of or into the middle of incidents and interactions. Also, it even provides a central plot device and premise for many episodes. It's even given rise to a number of philosophical thought experiments. Without this one decision, Star Trek would've felt very different and (most likely) weaker.

This wasn't the only time Star Trek's budget issues gave rise to creativity as well. David Gerrold, writer of the episode "The Trouble with Tribbles", wrote about the process of writing, rewriting, and filming the episode. Budget issues made him slim down the script and condense - for example - the space station bar and store into one single location which allowed for more easily-flowing action. Of course, the constraints of budget often caused problems and hurt the story, but here they did help by spurring creativity.

Other times, constraints can be internal to the author. For example, after four mystery novels about Lord Peter Wimsey, Dorothy Sayers was planning to marry her detective off and probably end the series. However, by the time she got to the end of her fifth novel (Strong Poison), she realized that as she'd set up the character of his love interest Harriet Vane, Harriet would not agree to marry Lord Peter just after he'd saved her life. She'd given Harriet too much of a drive for independence and self-respect for her to humble herself like that.

Faced with this constraint, Sayers decided not to run over it and have them marry anyway. Nor did she revise Harriet's character or the circumstances. Instead, she used it to spark more creativity: she had Harriet reject Lord Peter's proposal, and then she continued the series to develop their relationship and deepen both their characters. Six more volumes followed, extremely well-received, including (in my opinion) several of the best of the series.

Many other authors have admitted their characters drive story decisions. Another one that sticks in my mind as a constraint is Christopher Paolini. His Inheritance series was his first story, and - to put it mildly - it shows. A big reason I continued reading it, though, was to see his gradual development as an author. One moment that stood out to me was when he explained in an interview that he'd realized partway through writing Book Three that his protagonist Eragon, when he finds himself in hostile territory with his childhood-neighbor-now-enemy, wouldn't just abandon him despite their current differences. From this, Paolini decided to insert an entire new plot arc, lengthening his projected trilogy to four volumes. When I read that, I realized that Paolini really did have something of a good writer in him. He followed through on that in the fourth book, where (as he explained in another interview) he abandoned his whole originally-planned denouement because it wouldn't have been true to the characters as they'd developed.

I'm not saying that lengthening the story is the best way to handle it. Sayers wanted to write more books, but she could've just left things as they were at the end of Strong Poison without really harming the story as it was there. (Though it would've meant the series wouldn't have risen to its later heights!) Paolini, here as often, was writing clumsily. But as David Friedman (an occasional novelist as well as economist) says, "no plot survives contact with the characters." At least, it doesn't if the author's good.

I take this idea of constraints improving the story to be one aspect of the same point made by blogger Tom Simon, but from another angle:

It is not actually true that ‘all good writing is rewriting’. It would be nearer the truth to say that all good ideas are second ideas — or third, fourth, or 157th ideas. Writers are notoriously divisible into two warring camps, ‘outliners’ and ‘pantsers’. One of the most common triggers for a rewrite happens when you come up with a brilliant new idea halfway through a draft — and that idea makes a hash of everything you have already written...

That creative discomfort can make all the difference between great writing and dreck... [A good writer would ideally] have all the time he wanted to brainstorm, to throw away ideas when he came up with better ones, to tear up drafts, to indulge his creative discomfort.

Ideally, constraints - whether external, such as budget; or internal, such as established characters or worldbuilding - can spark that creative discomfort and cause an author to come up with new and better and more creative ideas that improve the story in the end.

Not every constraint, of course, will spark new and better ideas like this.

For example, in the last two decades of his life (after publishing Lord of the Rings), J. R. R. Tolkien kept revising Silmarillion. At first, the need to bring it in line with Lord of the Rings spurred further creativity. But afterwards, he got distracted by exploring the philosophical implications of what he'd written and trying to revise his ideas to correct their implications. For example, the charming tale of the different means of lighting the world would've been revised away in favor of an initial primeval Sun, and Galadriel's morally-conflicted past would've been revised to whitewash all her motives and behavior. In my opinion (and that of many other fans), had he finished any of these revisions, the story would've suffered for them.

In general, I think negative constraints (such as "you can't use a shuttlecraft model" or "you can't have Harriet marry her rescuer right away") will spur creativity better than positive constraints (such as "you must write a Silmarillion in line with modern cosmology"). Negative constraints leave more room for creative discomfort and better new ideas.

Of course, the regions forbidden by the negative constraints can't be too broad. Something like "Galadriel cannot have amoral motives" provides little room for characterization. Tolkien died before he could fully explore the implications of that, but I don't think it would have gone well. Genre constraints can similarly forbid many good stories from being translated between genres, as I described earlier talking about fantasy stories that couldn't be told similarly in other genres. The constraints by the characters of Eragon and Harriet Vane work better, because they have already proven themselves to be vivid characters, and what's negatively constrained is the plot around them.

This does imply that some forms of moral censorship can improve stories. When the author is willing to put up with it and work through the creative discomfort, I do believe that can be the case. Of course, it should be negative constraints to improve the work, forbidding certain elements or themes rather than requiring elements or themes. For example, I'm convinced that Robert Heinlein's science-fiction novels were often better earlier in his career when editors could still rein him in. They restricted his talk of sex, of nudity, and of politics, both in side references and in themes. He famously chafed at their control, and eventually escaped it after they rejected Starship Troopers entirely (thereby letting him activate the escape clause in his contract and go to another publisher). However, while there were some gems later (like The Moon is a Harsh Mistress), I think the quality of his books went down afterwards - and the Goodreads rankings agree.

A similar thing can happen in other disciplines, like architecture. For example, the famous steeply-sloped roofs of Swiss chalets came about so heavy snowfalls would slide off rather than build up and cause the roof to collapse. And, the famous pueblo appearance comes from how they're built out of local clay and designed to keep the inside rooms as cool as possible. Both of these iconic designs are inspired by the constraints put on long-ago builders by local conditions. Without the constraints, the end results might have been easier to build, but they would've looked less charming.

I'm not surprised to see this with published authors, because I've felt it myself. Many of the best ideas in my abortive novels or stories came from trying to reconcile two seemingly-incompatable constraints.

An author can come up with a story in one swoop, but ideally, an author shouldn't just be writing that single idea without further influences. Just like an author needs an editor, an author needs the creative discomfort of constraints to mold the story into its ideal form. For many authors, we can't see this because we don't see their creative process. But when we do see it, we see that the success of a story does indeed have many inspirations.

Mrs Whatsit: “How can I explain it to you? Oh, I know. In your language you have a form of poetry called the sonnet.”

…

Mrs. Whatsit: “It is a very strict form of poetry, is it not?”

Calvin: “Yes.”

Mrs. Whatsit: “There are fourteen lines, I believe, all in iambic pentameter. That’s a very strict rhythm or meter, yes?”

“Yes.” Calvin nodded.

“And each line has to end with a rigid rhyme pattern. And if the poet does not do it exactly this way, it is not a sonnet, is it?”

Calvin: “No.”

Mrs Whatsit: “But within this strict form the poet has complete freedom to say whatever he wants, doesn’t he?”

...from L'Engle's "A Wrinkle in Time"--a conversation about constraints that REALLY stuck with me.

Also, one of the most powerful things about stories is that it helps READERS to solve problems--not by reading stories until they arrive at one where the main character has the exact same problem as they do, but by watching someone else solve a problem and eventually... working out their own problem on their own. (Not sure whether the "brotherhood of people trying to do hard things" fellow-feeling of camraderie that they might feel with the character who they're watching solve problems or the "oh. you could DO that?!" surprise at seeing what the character does is more powerful for most people.)

So, of course, if you have the author "in the same boat" as well--alongside the main character and alongside an "in the market for solving problems" reader--struggling to resolve a problem within a story--that's even better!! And I would say that the FACT of the author taking on a difficult problem that he or she struggled to resolve... frequently GENERATES evidence of that hard work. But maybe we look at the outputs and simply see "a very good story." Which is quite enough. (:

> "I've tried to write novels. I haven't finished any of them... but I've gotten an inside view of at least part of that creative process."

I feel like the gift of getting the "inside view of the creative process" is a really awesome one too. Not one I had planned on or expected when I began writing fiction.

Constraints force you to find creative solutions to problems. For my work-in-progress novel, I want my protagonist to be a morally good person; she won't lie and cheat like the others at her school. That means she has to be clever to get ahead, which has the positive effect of making her smart and resourceful. It also means *I* have to be clever in writing her, so that's the cost - but I'm betting it's worth it.

Peter Jackson was originally contracted to make a two-movie adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, not three. He wrote the script with this in mind, paring it down to its very essentials. Then they decided to increase funding and allow him the space he needed. But the fact that the script had been mercilessly reduced was a huge boon in the end, because it meant the core of the story was rock-solid and they were able to add in some additional embellishments with the extra time. That's why the finished movies feel sleek and perfectly paced while also having a lush sense of worldbuilding. (https://www.polygon.com/lord-of-the-rings/22283921/peter-jackson-movies-lotr-alternate-versions-weinstein for more on this).