Common Sense

The bestselling little book that made independence popular

This continues my series marking the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the American Revolution. Previously was The Battle of Quebec, on December 31, 1775.

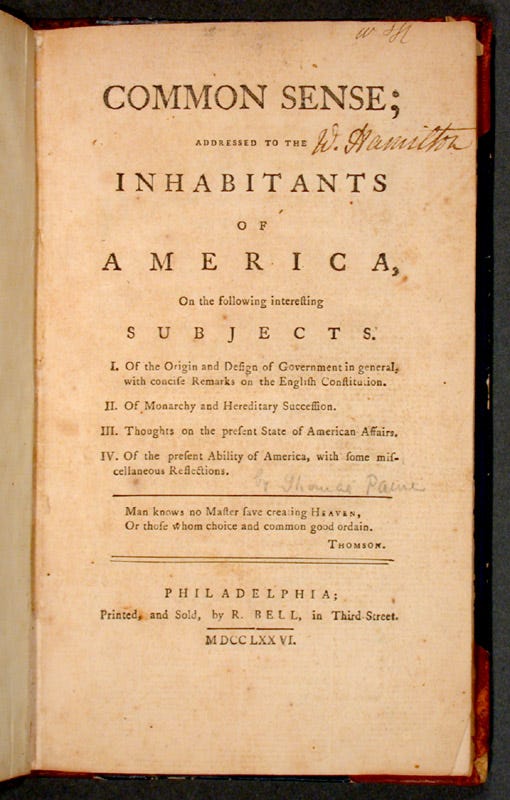

This week in 1776, the little book Common Sense was published.

It spread like wildfire across America, going through three editions in about a single month, and twenty-five in a year. It was reprinted by newspapers across America and read aloud in taverns and towns, far outdoing any other political book or pamphlet of the era. Quite possibly, it was the single most significant factor in turning the opinion of the American people toward independence.

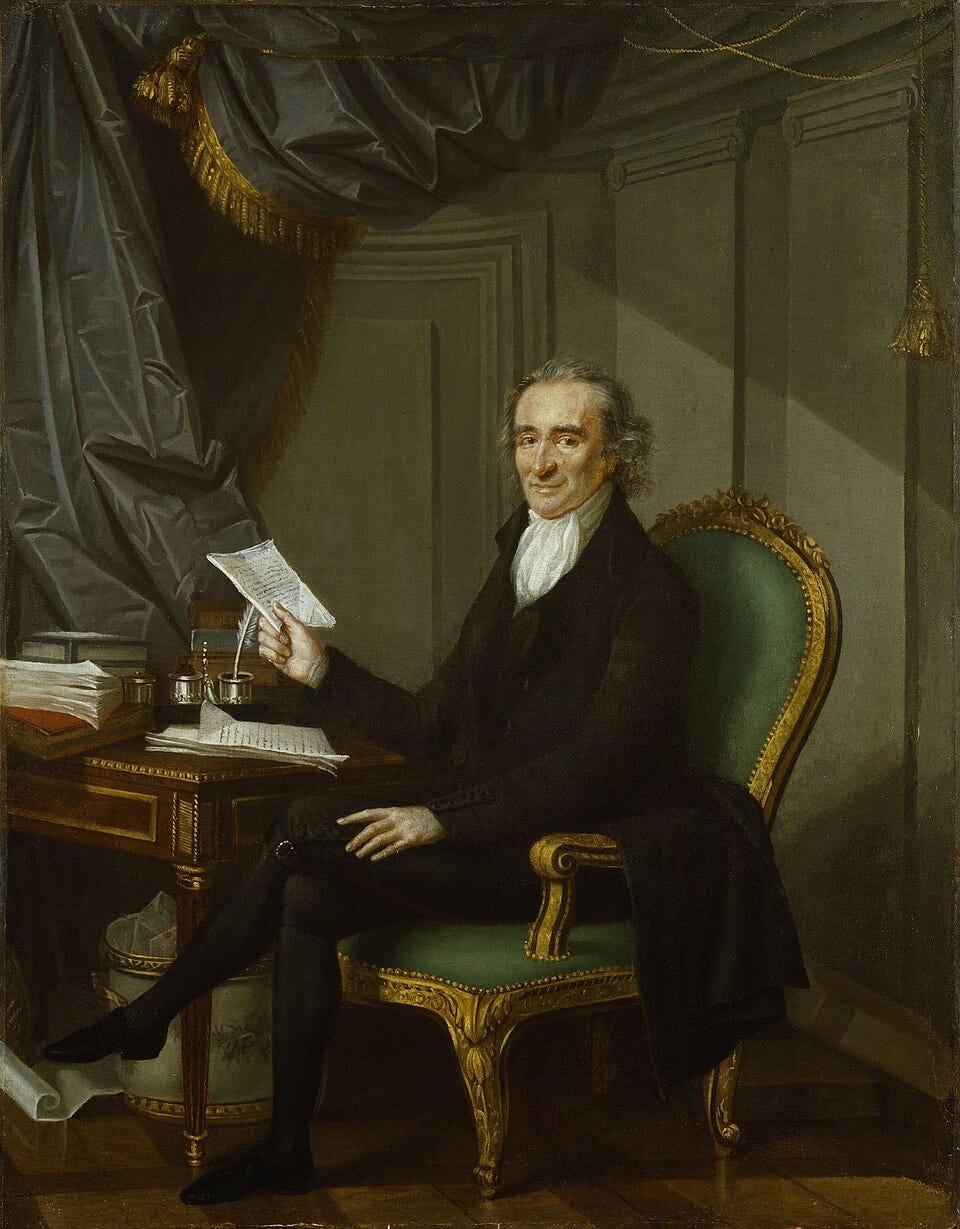

It was written by Thomas Paine, a recent immigrant from England who’d only arrived in 1774. He’d quickly adopted America’s cause as his own - since, as he put it, “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.” After America had won its liberty, he would return to England and France, where he would write in favor of the French Revolution and almost be executed for it. But that second revolution was still in the future in 1776, when he wrote Common Sense.

As he said in the title, he considered everything in his book mere common sense. He published anonymously - many people took the author to be someone of more note, like John Adams (who seems to have been not altogether pleased at the notion). But Paine wasn’t striving for recognition, but for the cause of freedom. As he put it in the introduction to his second edition, “Who the Author of this Production is, is wholly unnecessary to the Public, as the Object for Attention is the Doctrine itself, not the Man.”

A government of our own is our natural right; and when a man seriously reflects on the precariousness of human affairs, he will become convinced, that it is infinitely wiser and safer, to form a constitution of our own in a cool deliberate manner, while we have it in our power, than to trust such an interesting event to time and chance.

Common Sense was written to be a short and easy read. It’s still a quick read, unless you want to pause to ponder all the images and arguments Paine puts on the page, which often aren’t so commonplace anymore as they were then.

Paine viciously tears apart the idea that any king has any rightful authority anywhere, and ridicules it from many different directions. Kings, he says, were mere bandits who’ve surrounded themselves and their heirs with mystique; perhaps unavoidable at some time, but not owning our allegiance. And in case any reader might still credit kings in general due some loyalty, he tears apart the idea that Britain or “the royal brute of Britain”, specifically, has any rightful authority over America.

He then looks at the practicalities. This was January 1776; the war with Britain was already well underway. But, he argues, it’s been held back by how the colonies still acknowledge some theoretical allegiance to Britain. And that theoretical loyalty is useless - even assuming America somehow reaches reconciliation with Britain, how would any peace agreement actually keep America’s rights secure? What benefit would America get from reconciliation, aside from simple peace? Rather, Paine concludes, only full independence would make the war be worth anything.

This’s passionate, and cogent - not bulletproof (I can still see some theoretical holes in his arguments), but very strong. What’s more, Paine makes it understandable to the average person. He doesn’t dwell on theoretical arguments about social contracts or natural rights (like Locke and Hobbes, and even the Declaration of Independence, all began with); he keeps the focus squarely on the practicalities of how societies work. Even when he’s painting a picture of a supposed primitive society before kings, he paints it vividly with phrases like “Some convenient tree will afford them a State-House, under the branches of which, the whole colony may assemble...”

His rhetoric is excellent. He makes it seem, indeed, common sense. I can totally see how his book swept America like a tidal wave.

By referring the matter from argument to arms, a new era for politics is struck; a new method of thinking hath arisen. All plans, proposals, &c. prior to the nineteenth of April, i.e. to the commencement of hostilities, are like the almanacks of the last year; which, though proper then, are superseded and useless now...

John Adams, writing to his wife Abigail Adams in mid-March, had the same opinion: “Sensible men think there are some Whims, some Sophisms... some keen attempts up on the Passions, in this pamphlet. But all agree there is a great deal of good sense, delivered in a clear, simple, concise and nervous [i.e. forceful] Style. His Sentiments of the Abilities of America, and of the Difficulty of a reconciliation with G[reat] B[ritain] are generally approved.”

Events helped, of course. Before the war - even in Massachusetts - Patriots like John Adams and Joseph Warren had held back from even mentioning they favored independence. They knew the people weren’t ready to hear it, and it would merely frighten them away from the Patriot cause. But after months of war, things had changed.

Men of passive tempers look somewhat lightly over the offences of Britain... if you say, you can still pass the violations over, then I ask, hath your house been burnt? Hath your property been destroyed before your face? Are your wife and children destitute of a bed to lie on, or bread to live on?... if you have, and still can shake hands with the murderers, then are you unworthy the name of husband, father, friend, or lover.

Paine was of course speaking for effect - but he was speaking of things that had just happened. The British fleet - under Dunmore in Virginia, Gage in Massachusetts, and others elsewhere - had bombarded several towns. Children had been left “destitute of a bed to lie on.” Not many had, but some had - and as the news sped through America, and the war continued, many could imagine the picture Paine was painting.

But Paine didn’t just paint that picture; he offered a new frame to interpret it. He presented people with a new paradigm: Britain wasn’t their mother country any longer; America should simply cast it off and declare independence.

And events as Paine was publishing put this question even more starkly. On the same day Common Sense was published, Philadelphia finally learned that King George, back in October, had declared the colonies officially in rebellion and promised to firmly suppress the rebellion. As Paine later assessed, “Had the spirit of prophecy directed the birth of this production, it could not have brought it forth at a more seasonable juncture, or a more necessary time... The Speech, instead of terrifying, prepared a way for the manly principles of Independence... The speech hath one good quality, which is, that it is not calculated to deceive, neither can we, even if we would, be deceived by it. “

The Founding Fathers in the legislatures and the Continental Congress never directly cited Common Sense. They didn’t need to. What Common Sense did was put new words to the arguments that were often already present, and to bring out cogently the implications of events. Common Sense changed the public mindset so that the Founding Fathers could organize new governments and declare independence.

George Washington, in March, wrote that “by private letters which I have lately received from Virginia, I find Common Sense is working a powerful change there in the minds of many men” toward “independency.”

John Adams, in April, attributed the change to “the Royal Proclamation, and the late Act of Parliament” (that is, King George’s declaration that the colonies were in rebellion, and the Prohibitory Act of December 1775 which prohibited the colonies from all foreign trade), but agreed that something had “convinced the doubting and confirmed the timorous and wavering.” Being crotchety as he was, he later wrote in another letter that “I have never heard one single person speak well of any Thing about [Paine] but his abilities, which are generally allowed to be good.” Whether or not that was correct, Paine’s anonymously-published words far outran his personal reputation.

Paine, in his preface to the third edition of Common Sense in February, commented that “no Answer hath yet appeared” to try to refute Common Sense. A few eventually did, but none had anywhere near as much circulation or popularity. Common Sense did indeed, in the minds of Americans, become common sense.

I read somewhere a long time ago - I forget where - that while the best-known symbol of the French Revolution was the guillotine, the best-known symbol of the American Revolution was the Declaration of Independence. In other words (this author put it), unlike many other revolutions, the American Revolution was characterized by reasoned argument and peaceful voting.

That author might be unfair (as Paine was too at several points), but he’s not really wrong. Common Sense reminds us of this.

I’ve been writing a lot about battles and campaigns, because they’re notable and they can be pinned down to a specific date on a timeline. But, as Adams put it long afterwards, the real Revolution “was in the Minds and Hearts of the People”. If the people of America hadn’t wanted to stand up for their liberty - if they hadn’t come to want independence - all the armies would’ve fallen apart and the battles and campaigns would have come to naught. It was the people of Massachusetts who streamed from their farms to fight the Redcoats at Lexington and Concord; it was the people of New England who were still keeping British soldiers bottled up in Boston as Paine wrote; it was the people of America who would push forward to final independence.

Paine, himself, wasn’t anyone except a voice. But his words dug a great part of the foundation on which America was built.