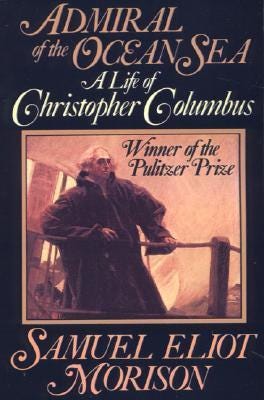

Several weeks ago, I read a lengthy biography of Christopher Columbus - Admiral of the Ocean Sea, by Samuel Eliot Morison, published in 1942.

This book was published before all the modern controversies excoriating Columbus for enslaving the Caribbean Indians (which he did indeed do), so it doesn't shy away from calling the reader's attention to Columbus's virtues, using that word. I'm glad - I'd heard other people call my attention to Columbus’s vices, and I wanted to find out what sort of person he was to a more sympathetic eye.

(More specifically, I'd seen Columbus's mostly-sympathetic portrayal in the time-travel novel Pastwatch by Orson Scott Card; I wanted to see what he was to a sympathetic actual historian.)

I'm glad to have read a book sympathetic to Columbus's virtues, because now I can more definitely say: he didn't have many of them.

Well, he had a lot of them in the Aristotelian sense, where the philosopher used “virtue” to mean how well something lives up to its epitome. Columbus had good skill at inspiring his crews to keep going, very good navigational skill for his era, and excellent dogged determination and persistence. Morison calls out all of these repeatedly, and I agree. I'm inclined to qualify the navigational skill - no one had great long-distance navigational skill in 1492, but Columbus was at or above par there and excellent at short-range navigation around (say) the uncharted islands of the Caribbean. But these Aristotelian virtues fitted Columbus beautifully to approach the epitome of being a discoverer and explorer.

All the private trailblazing explorers of the later Age of Exploration can look up to Columbus as their model in determination and skill. He would have been happy among them, too. In fact, he would probably have been much happier there, where explorers could stump around for funding from the public, than in the 1400’s when he had to spend year after year petitioning the courts of western Europe to fund his first voyage - and then petitioning King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella again and again for further voyages and the recognition he was technically owed.

He would also have been happier in the later Age of Exploration than trying to actually govern a colony. Columbus's skill at inspiring his crew only lasted while they were indeed at sea. From the moment the Santa Maria sunk off the coast of Haiti on his first voyage, and he had to leave some of his seamen behind as an unplanned colony, things started to go wrong. Things kept going wrong after he returned on his second voyage, with intentional settlers and a royal commission as governor. All along, the settlers flouted his authority, assaulted and mistreated the Indians, and generally kept things in disorder. To be true, Columbus wasn't averse to enslaving the Indians to some degree - but he never allowed the personal impressment and sexual exploitation his settlers were doing, and he lamented it when he saw it. Finally, their constant complaints against Columbus caused King Ferdinand to send a new governor, who (upon seeing that Columbus had just bloodily quelled a rebellion) sent Columbus home in chains. Columbus was a good explorer, but a very bad governor.

That said, even without such unruly prideful colonists, he would have been in a hard situation as governor.

Columbus had promised his sponsors, Ferdinand and Isabella, all the gold and spices of Asia in trade. Instead, he gave them a few nuggets of gold from the Caribbean islands. But Columbus responded very poorly to that hard situation. He felt forced to enslave the Indians in search for the gold. Even that, though, proved lacking, and the voyages attacked as a waste of money. So, he started shipping prisoners of war back to be sold as slaves, as was then accepted practice... and when even that didn't prove enough, ship more slaves.

He was a good explorer, but - it appears even from this book that praises him - not a particularly good man.

While reading this biography, I also kept my eye out for clues to why Columbus's voyages led to lasting contact between Europe and the Americas.

Columbus wasn't the first European to sail to America. The Vikings had gone there about five hundred years earlier, after discovering North America while being blown off course on the way to Greenland. They kept periodically coming back for lumber, but their voyages made next to no impact on anyone or anywhere else. It's not impossible other Europeans might have come to America before Columbus too, but if so they left even less impact. So why was Columbus different?

Columbus, of course, had been promising a way to get to Asia. He'd promised riches and splendor. To his dying day, he kept promising they were right around the corner. He was convinced that his discoveries were just a little ways away from Asia - that Cuba was part of China, and the Central American isthmus was the Malay Peninsula. But he was wrong. He didn't find any riches or splendor. And yet, further voyages and settlers did follow, until finally Cortez did find something of those riches in Mexico.

(Orson Scott Card's novel Pastwatch suggests that Columbus thought he'd heard God’s voice promising riches and wonder across the ocean. That’s an invention for the novel; there's no reason to believe it's true - except that Columbus historically seemed as certain as if he'd heard that Divine voice.)

I think that's one reason contact continued: the lure of Columbus's confidence. The Vikings had no reason to expect gold or anything except lumber. But Columbus's contemporaries heard about his discoveries in the same breath as they heard his confidence they were right next to riches.

This gave the news faster wings than the news of the Vikings' discovery. The first surviving writing about "Vinland" (as the Vikings called North America) just mentions it as islands discovered by the Norse - no more exciting than Greenland itself. It's no surprise no one except other individual Norse sailors followed up on that for centuries. But Columbus wrote about fruitful lands in terms promising riches.

But after that, another difference was the scale of expedition possible. European banking had recently established a semi-functional credit system. Even though European states didn't have that much more absolute revenue, they could borrow enough to have more ready cash than before. So, Isabella of Spain could credibly promise to mortgage her jewels to fund Columbus - and then she and her husband could actually borrow money on the promise of future state revenues.

This meant that Spain and other European realms could send out much larger expeditions than their predecessors, let alone individual Viking adventurers. For the Vikings, each man (except a few thralls) was an individual volunteer, and the ships were individually owned by people aboard. If they weren't interested in staying around, they just went home. Most Spanish colonists, however, were employees of the Crown, and most every ship home was owned by the Crown or a few noblemen (like Columbus himself). Individual colonists might and did want to leave once they found scarce gold, but they usually didn't.

And then, a few decades later, one Spanish adventurer (Cortez) found the treasures of Mexico... and it turned out another part of Columbus's mad certainty was true after all. Everything changed again, because now people knew there really was treasure in the New World.

Columbus was an interesting man. He was certain Asia was close and accessible, despite many good reasons to think otherwise. Then, he was certain he had indeed found Asia with treasures right around the corner, even as evidence built up otherwise. I can see why Card, in his novel, posited Columbus believed he'd seen a vision from God!

But then - Columbus's unwarranted confidence, and his practical navigation skills, let him turn the rudder of history.

That also landed him way over his head, both in moral temptations (which he failed) and politics (where he also abjectly failed). He should have kept exploring. That would, in the end, have been a better reward than being the viceroy of the Spanish colonies (which he'd actually demanded). But Columbus wouldn't give up the reward he'd demanded, which landed him in more and more struggles with King Ferdinand that didn't help anyone.

Columbus did see he'd set the tiller of history to a new course. He was abjectly wrong about what the course was. He was convinced the riches of the East would shortly come to Europe to fund a new Crusade that would reclaim Jerusalem and bring in a Golden Age. None of this happened. Riches did come to Europe, but they instead funded far different wars inside Europe, among other things. We could say a Golden Age eventually came, perhaps because of this; but it was thanks to an Industrial Revolution centuries later which Columbus hadn't anticipated. This should lead us to humility.

But this is nothing new. Martin Luther was convinced he'd reform the one church, rather than split it; Paul Revere was convinced his place in history would be as a politician and general; many other people were similarly mistaken. If Columbus was different, it was in how long he persisted in his mistaken idea of history's course.

Still, Morison keeps reminding his readers, we shouldn't be surprised Columbus didn't change his mind. If Columbus had been willing to give up his ideas in the face of convincing contrary evidence, he wouldn't have sailed across the Atlantic to Asia in the first place. He wouldn't have been Columbus.

If you want a newer pro-Columbus book, I saw a YouTube about this one. Columbus, according to the book, wanted to fund a crusade to recapture Jerusalem. He thought the Chinese were Christ-curious and thought he could enlist their help and use proceeds from trade to fund it. Most of the atrocities happened because Columbus couldn't keep a leash on his men, not because he wanted them to happen. (I'm not arguing for one interpretation or the other)

https://www.amazon.ca/Columbus-Quest-Jerusalem-Religion-Voyages/dp/1439102376