Boston and the Changes of Modernity

I recently visited Boston and had a great time touring so many historic sites. One of the top items on my list, of course, was Paul Revere's house.

Sadly, Revere's original workshop hasn't been preserved. That, as well as so much else of old Boston, has fallen before modern development. The historical buildings that remain are nestled among modern skyscrapers. The Bunker Hill battlefield is now urban condos, save for one small memorial park at the site of the American fortifications.

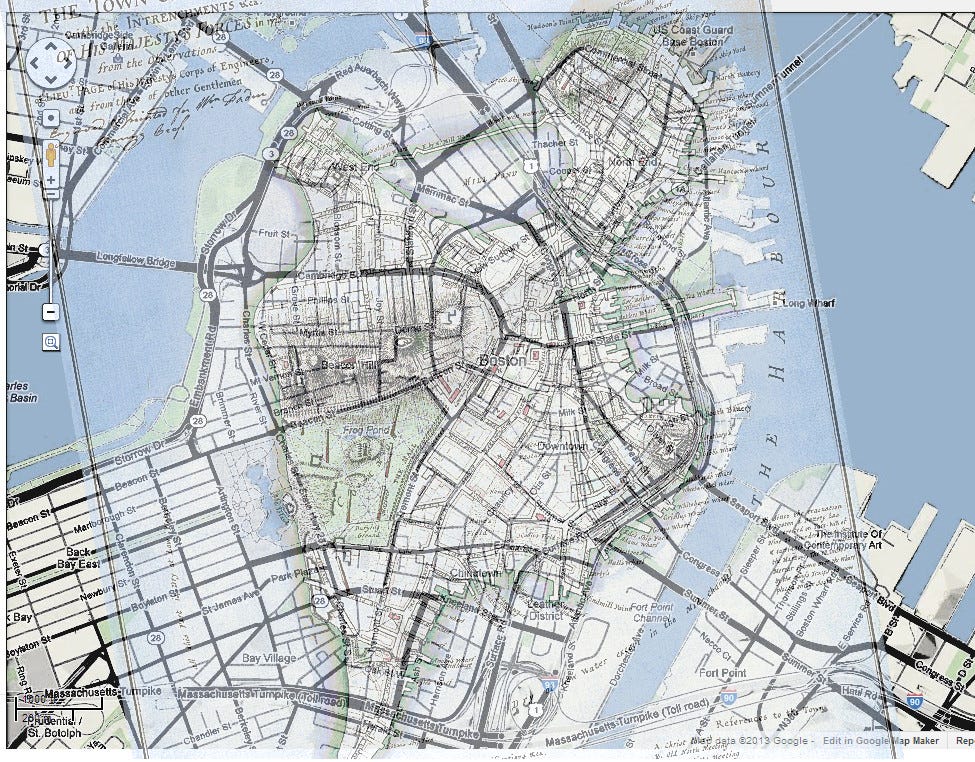

In fact, Boston - even the middle of Boston, to say nothing of the outer reaches of the city that were countryside at the time of the American Revolution - has changed far more than just building new buildings. The very coastline of Boston has changed over the centuries, thanks to land being filled in, until it's almost unrecognizable. The Charles River is now a river rather than bay; the Customs House that was at the coastline is now several blocks inland; Boston Neck has vanished to be replaced by the "Back Bay" neighborhood. (The British soldiers marching to Lexington and Concord departed "by sea" from Boston Common, in what's now the Public Garden.) And, several hills have also vanished to provide the earth for this fill; Beacon Hill is one of the only survivors.

But all this can be taken as a monument to a newer type of city, and a newer chapter in human history. On one level, we could look at modern technology, exemplified by the famous university MIT just across the Charles River (in still-independent Charlestown) on land that was still water at the Revolution. But on another level, it's deeper than merely technology.

While on the way back from Boston, I was reading a very interesting book - The Domestic Revolution by Ruth Goodman - about the consequences of people in England starting to burn coal instead of wood. There were many disadvantages of coal, such as how difficult it was to light it on fire, how foul the smoke smelled, and how difficult it was to clean smoke stains. (Goodman argues that it was coal that led to the popularity of soap in the first place.)

But the one big advantage was that it was available - and that it was available however quickly you were able to mine. Beforehand, if you wanted more firewood, you needed more land to plant trees on to grow into firewood. In the late 1500's, as English cities (especially London) were growing, they needed more and more firewood. That meant more and more land was needed for forests, wood was being shipped farther and farther, and prices were rising. There was no way out of this problem as long as they depended on land and weather. What they had to do was switch to a totally new way of doing things that got around the natural pattern of annual growing seasons.

Boston sort of did the same thing, by building land out into the sea. Then, it did the same thing again (following London's model), by building rail lines through the city to bring people in faster than muscle power (whether human or animal) could move them.

We can see the huge impacts of this all around us. Even our modern farms are carefully tended both above ground level (with harvesters, planters, sprayers and so many more machines) and below (with irrigation systems and modified seeds). All these improvements mean that, for the first time in human history, most people now live in cities. Even as early as 1838, as the Bunker Hill Monument was being constructed on the battlefield of Bunker Hill, much of the battlefield was being sold as house lots. The whole neighborhood is now part of the Boston urban core.

Even among the historical sites in Boston, Revolutionary-era sites were interspersed with more modern and technological things such as posters about the first subway in America (now part of the MBTA Green Line), the 1900 Longfellow Bridge, a museum of the Olmstead park system, and (of course) the "Big Dig" highway tunnels.

This juxtaposition kept standing out to me in Boston. One of the things I saw there was the USS Constitution, the oldest ship still afloat, a sailing ship launched in 1797 for the fledgling US Navy. It was fascinating to visit, and extremely well kept-up. (It's still commissioned in the US Navy; the Navy keeps up a special grove of white oak to be ready for patchwork when necessary.) But as I was looking around it, I was also struck by how small it was. It was one of the largest and best US Navy ships in its day, but now, even the World War Two - era destroyer USS Cassin Young docked next door to it is larger.

And yet, the USS Constitution is still around. The Old State House is also preserved amid the skyscrapers, as were Paul Revere's house, the Old South Meeting House, and so many other places. A monument in Cambridge Commons, just off the Harvard campus, points out the tree under which George Washington officially took command of the Continental Army. Old North Bridge at Concord, the site of the shots that started the Revolution (where the Massachusetts militia being ordered to fire on British troops) was even reconstructed as a footbridge and monument after the modern road bridge bypassed it.

I'm glad for this. On the one hand, the preserved historical sites make history come alive so vividly. On the other hand, the juxtaposition of them with the modern city makes a different part of history come alive just as vividly. Both are good things; both are important.