An Attempt at Cuckoos

"The Midwich Cookoos" and not writing the story you're wanting

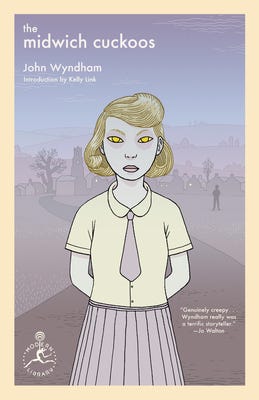

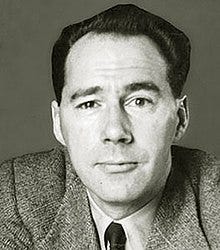

I was thinking again recently about John Wyndham, a British writer of dark science fiction from the mid-twentieth century. He's written several famous books, such as Day of the Triffids, but the one that sticks most in my mind is the disturbing The Midwich Cuckoos (later turned into the film Village of the Damned).

It's a disturbing story, in multiple senses. I didn't enjoy it. The events would be disturbing to read about anyway - but because of how it's told, I ended up in some ways reading a different story than Wyndham tried to tell. And that left me with an uncertainty that disturbed me in another way.

Wyndham writes of (as his characters describe it inside the novel) an unexpected and disturbing form of alien attack: in a cozy isolated English village, they put alien children inside the wombs of all the women of childbearing age. Except, only a few people guess that at the time - we get to watch the women realize that they're surprisingly pregnant by unusual means. After some debate, it's decided to welcome these children despite their unconventional arrival. The welcome nervously persists despite their odd appearance (the book is written before DNA was discovered so we don't get those tests), their starting to reveal occasional mind-control abilities, and despite their having telepathy among themselves. It somewhat frays - but only somewhat - when their telepathy develops into hiveminds.

Meanwhile, our protagonist and his loquacious friend Zellaby (both men in the village) are speculating about what this might mean. Zellaby rushes his daughter out of the village lest the children's mind control get even more widespread. Zellaby notices these children have clear advantages over normal humans, and speculates that they're invaders set to outcompete and obsoletize humanity. He keeps comparing them to the cuckoo.

Finally, when the children are nine years old, a man accidentally hurts one of them - and the children kill him by mind control. When someone else tries to kill one of them in revenge, they kill him too. Then, one of the children explicitly says that yes they are exactly what Zellaby has been speculating they are. The government wrings its hands, and only individual action to kill these invading alien children can save humanity...

Told baldly like this, this sounds like a horror story. But it barely reads like that; the tone is much too cozy up to the very end. The premise could've yielded an action story, but there's next to no actual action here. Or it could've been played as one of many allegories: the divide between generations, parents' changing priorities once they have kids, social shifts in the world... but none of these allegories are even attempted in any scene. What we do have is a juxtaposition of disturbing events and cozy tone. Even this yields some horror in itself - but it's never drawn out. Until the very end, the disturbance is discussed in the most scientific of terms. I keep thinking this book doesn't use its premise to its best in any of the ways it could.

And frankly, as I think of the ending, I'm more with the government than Zellaby. I see what Wyndham the author tried to write, but what he actually wrote on the page doesn't make his case.

Zellaby's right that, considered in the abstract, these alien children are a clear threat to humanity. But inside the book they're only a threat. They've only hurt people who've hurt them, and before the last week of the book not even that. When I was reading the book, I kept thinking how far Zellaby was speculating, and waiting for events to bare out his theories. But they never did.

(Yes, as infants, they were mind-controlling their mothers to stay in the village with the other children. But I'll pardon everything they did in their infancy. Real human infants would mind-control their mothers all the time if they could, including to stay with their playmates.)

Well, we do have that one time at the end when one of the alien children admits to everything Zellaby has been saying. In fact, he parrots Zellaby's views almost verbatim. But because he's parroting them like that, I can't help thinking he got the idea from Zellaby. We know that human children can take into their self-image the descriptions they've heard from others. We know Zellaby's been helping tutor these kids (so as to keep a better watch on them). It would be unlike him to tell them his theory, but could they perhaps have read it from his mind? This's speculation, but it came to me the moment I read that speech, and I think it's justified.

In the real world, Wyndham the author clearly agrees with Zellaby. But within the world of the story, I think this theory is as justified as Zellaby's. Zellaby would call me a naive fool - but I'm concerned Zellaby might be an overparanoid murderer. If the children had been left alive, and perhaps even raised by more loving people, would things have gone differently?

I can't help wanting to see that story. Perhaps it would have a far more friendly end. For all we know, their alien parents might be watching and judging humanity based on how it treats their children. Or it could be a less clear end that allegorizes generational divides, like I suggested above. Or perhaps it would turn out more tragically - but we would know then the tragedy was inevitable, and the characters would have been nobler and more moral representatives of humanity.

From the narrative tone and perspective, I'm sure Wyndham the author did mean Zellaby's theories to be correct. His other stories, involving real hostile nonhuman powers - such as the nuclear fallout in The Chrysalids and the carnivorous plants in Day of the Triffids - make me even more sure. So how did he fail in this book?

This narrative's fundamental challenge is that it must be a story about a mere threat. Once these alien children grow up and start seriously outcompeting humanity, there's no longer any realistic way of defeating them. Or, at least, it would be a much more national-scale story than Wyndham is used to telling. So, we must defeat them when their frightful deeds are just potential.

In other words, Wyndham must tell us about them (in potential), not show them to us.

This violates a standard maxim of writing advice: "Show, don't tell." There's good reason for this maxim - readers want to see what's happening. Among other reasons, it'll feel more real to them, and they'll know for sure it's happening. This was the major reason I didn't enjoy the book: Wyndham repeatedly tells us without showing.

Perhaps Wyndham would say he has shown us the alien children's danger: they've mind-controlled their mothers, and they've killed two men who hurt them. But, this doesn't convince me, because - as Wyndham reiterates throughout the novel - we're dealing with aliens. They had reasons for killing these two men. Granted, they're not reasons that would pass muster in modern human society, but they're reasons a human can understand. More than that, they're reasons that would have been acceptable in some past societies. Looking at that in isolation, I would say it's quite possible these alien children could still be reasoned with... and I did think that when I first read the book.

(And as I said above, they mind-controlled their mothers in infancy; human infants would do the same if they could.)

Of course, Wyndham meant this to be a sign they aren't able to be reasoned with; they're a clear and present danger. But he didn't actually show it. His half-showing didn't convince me.

Wyndham didn't quite write the story he meant to write. But he came close to it. For most readers, it does come close enough - on Goodreads, most of the reviews accept Wyndham's explanation from Zellaby's lips. This's a good point in itself: flaws often don't matter to many readers.

Besides, Wyndham's story is filled with evocative images and questions. And for readers like me who do see the gap, the story raises even more questions he didn't mean to put there.

The first Wyndham I read was Re-Birth (the title it appeared under in Anthony Boucher's A Treasury of Great Science Fiction). It shows a group of telepathic children/adolescents growing up in a fundamentalist society that regards mutations as offenses against God. Near the end, they are rescued by a party from New Zealand, where everyone is telepathic, and one of their rescuers says, "In loyalty to their kind, they cannot tolerate our rise. In loyalty to our kind, we cannot tolerate their obstruction." (Jefferson Airplane paraphrased this line in their song "Crown of Creation," changing "rise" to "minds.") So it appears that Wyndham characteristically thinks in terms of species as discrete and hostile entities, even when they are not actually species by the biological definition; that is, in terms of racial or biological collectivism. This suggests that the fundamentalists of his future Labrador are actually right, even though he encourages the reader to sympathize with the telepathic children instead.