The other week, I read a book by US Navy Institute professor Bruce Elleman with a provocative thesis: that the Japanese internment camps in the United States in World War II were a good thing.

Elleman approaches this from a unique and legitimately informative perspective, which you can see from his book's title: Japanese-American Civilian Prisoner Exchanges and Detention Camps, 1941-45. He digs into the detail of the Japanese-American negotiations during the war about exchanging their nationals caught behind each other's lines. This was interesting to read; he writes well, and taught me a lot. But then, he argues the internment camps were necessary and fit to make this possible. Here, he makes many leaps and generalizations from his facts.

I'll start where Elleman does, with prisoner exchanges.

Prisoner exchanges between the different countries in a war go back to the ancient era. Perhaps the height of the prisoner exchange system - both in volume and formalization - was in the US Civil War. There was a formal prisoner exchange cartel, where each side would usually exchange the same number of prisoners of each rank; any extras would have to wait in captivity. Between this and both sides' willingness to surrender rather than be killed, huge numbers of soldiers were exchanged quite quickly. A soldier could surrender, be exchanged, and then be fighting again a few months later.

However, this system broke down later in the war. The first big problem was that the Confederates refused to exchange black soldiers, insisting on treating them as escaped slaves. But then, General Grant decided to not try to reenstate it, because he hoped to exhaust Confederate manpower. Both these disagreements - disagreements about who would be exchanged, and whether exchanges were even a good thing - would crop up again in World War II.

Usually, of course, the prisoners were soldiers.

Elleman describes how the Japanese and American governments, in World War II, built upon this tradition to exchange civilians in the middle of the war. A number of Americans had been traveling or working in Japan before the war, and even more had been working in other parts of Asia and caught by the Japanese invasion. The American government was eager to get them back for humanitarian reasons, especially since the Japanese were (correctly) rumored to be keeping them in harsh conditions. Meanwhile, the Japanese government hoped to get a number of Japanese who'd been studying or working in America, especially technical workers and students who would be useful to its war effort.

Elleman tells an interesting story of the laborious negotiations between Japan and America. They were doubtlessly even more laborious to the people involved, since every communication had to go through the intermediary "protecting powers" of Switzerland and Spain. Neither Japan nor America trusted the other, so every detail needed to be argued over and spelled out down to the exact dates the ships carrying the people would leave and where in neutral territory (Portuguese Africa for the first ship, and Portuguese India for the second) they would meet.

Two Japanese conditions made the exchanges far more difficult: they required that identical numbers of people would be exchanged, and identical numbers of people of each social status. So, for example, if Japan was freeing fifty American doctors, they insisted that America send them fifty Japanese doctors. In a class-sensitive Japanese society, this made perfect sense. They wanted respect; they wanted their educated men to be considered the equals of American educated men.

However, most Japanese-Americans didn't want to return to wartime Japan. Even worse, the ones who did want to return were mostly uneducated farmworkers. The Japanese government was much less interested in getting them back, let alone exchanging them for educated Americans - and they didn't even hold any American farmworkers to exchange for them. Instead, they kept repeatedly (through Spain) expressing disbelief that educated Japanese wouldn't want to return, and accusing the American government of keeping them prisoner.

Two exchanges ended up happening, freeing 3,000 Americans, before the Japanese government indefinitely postponed a third. A remaining 6,000 Americans, and 20,000 Japanese who'd expressed a desire to return to Japan, remained in custody through the rest of the war.

The accusations of keeping them prisoner weren't totally made up.

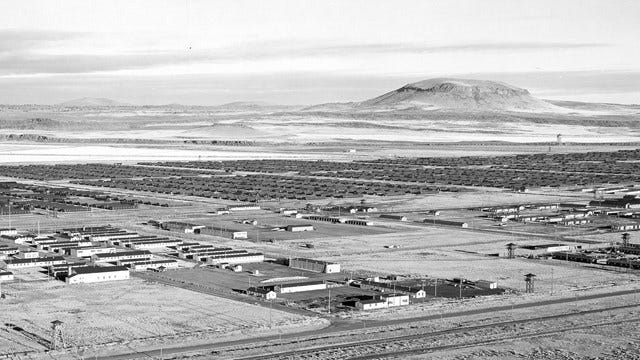

To do these exchanges, Elleman says, the United States government needed to locate Japanese who wished to be exchanged, and keep them safe in a place where they could quickly load the exchange ship when it was agreed to sail. So, he argues, the wartime internment camps for all Japanese-Americans from the US west coast were a necessary thing; a good thing.

However, Elleman doesn't cite any actual evidence this was the reason behind the internment camps. He describes the exchange program as a glimmer in the eyes of the State Department, a mere vague potential hope, in early 1942 when the internment was happening. The US military commanders who ordered the internment, and the local officials who carried it out, justified it on the grounds of military safety. Many Japanese-Americans, they claimed, would happily sabotage the war effort to support Japan. Elleman doesn't quote anyone actually involved in that process at that point bringing up prisoner exchanges. He talks at length about the process of running the camps later, but nothing about setting them up.

Instead, when Elleman talks about the setup process, he claims the fears of sabotage were justified. The only evidence he offers is a pre-war cable from the Japanese embassy claiming they had saboteurs in place - which sabotage, Elleman argues, was stopped by the internment program. However, I doubt whether these saboteurs were even real, rather than just a brag. Or if they were real - which also wouldn't surprise me, given how some Japanese-Americans in the internment camp would later openly express their desire to aid the Japanese war effort - nobody claimed in this message, or elsewhere in Elleman's book, how many there were.

Could this minority of potential saboteurs justify interning all Japanese-Americans?

But I'm happy to talk about hypotheticals. We can reframe Elleman's argument as saying that the internment could have been justified on the basis of the prisoner exchange program.

What Elleman neglects here - and on the sabotage argument as well - is, curiously, a point he keeps coming back to in his narrative. When the State Department actually did send out questionnaires about the exchange program - 84 percent of the Japanese-Americans in the camps - ~100,000 out of ~120,000 - swore loyalty to the United States, expressed willingness to serve in the US war effort, and refused to return to Japan.

The Japanese government expressed incredulity at this, but it was the case. Even though the American government was holding these people in camps, they were still happy to help the American war effort. Perhaps they correctly concluded the Japanese government would have scarcely cared for them any more?

But whatever the reason, the US government never contemplated sending them back by force. Nor should they have. Once they'd refused repatriation, until and unless they changed their minds, the exchange program offered no justification for keeping them interned. So, why was their internment part of this program? Elleman keeps coming back to how the US government was very aware of this difference, even at one point concentrating everyone who wanted to return to Japan in one single camp. But he doesn't seem to notice how this affects his central claim about the camps.

Elleman does, at one point, offer another argument for how the camps were necessary: without internment, mobs might have attacked the Japanese-Americans. He cites some examples, and I agree this isn't implausible. And, if this had happened, no doubt the Japanese government would have loudly protested. (They did repeatedly protest about conditions in the camps; Elleman goes to some length to spell out how their repeated accusations of mistreatment or forced labor were all incorrect.)

But, none of this justifies forced internment. There were other ways, such as offering them the voluntary option of relocating.

Eventually, Japanese-Americans were allowed to leave the camps if they found other homes for themselves away from the Pacific coast. Unfortunately, this was too little too late - their careers and familiar communities had already been taken away from them. Elleman talks about how the camps had themselves become new communities, well run in many ways, and I'm glad. But they could have been better.

The Japanese-American repatriation exchange program was a good thing sadly cut short, and I'm glad that Elleman brings it to light. I'm struck by the two governments' very different attitudes toward protecting their people, which is one very real part of the reason the war went the way it did. This was why it was cut short: the Japanese weren't interested in getting back the people who wanted to return to Japan.

But Elleman's book is sadly marred by trying to conflate this exchange program with the whole internment program. There were other aspects and reasons there that his book (and presumably his research) doesn't talk about.

He has good facts, but he tries to use them to explain too much.

A couple of things. First, Elleman isn't a professor at the US Naval Institute. USNI doesn't have professors. He's a professor at the Naval War College, and has written something for USNI. (This is less impressive than it sounds.) Second, I think it's worth pointing to the Niihau incident for how people were evaluating the probability of sabotage. Yes, it turns out that we didn't see the sort of problems out of the Japanese that we saw with, say, the Germans in WWI, but given what happened at the start of the war, that wasn't the way to bet. If Elleman didn't bring that up, then he did a terrible job of making the argument.

One of the things I've wondered about is did the Japanese Internment prevent an American Kristalinacht? The internment was very strange. It only applied to three states (WA, OR, CA) and the four western most counties in AZ. It was actually a relocation or internment order. If a Japanese family moved 150 miles plus eastward, no internment. Didn't apply to Hawaii. Canada had a similar program which I believe applied to the entire country and also applied to Eskimos and Inuits, which the US didn't.

Very little is written about the Italians (first to be interred) or the Germans.

I suspect most Americans couldn't tell the difference between someone who was Chinese, Filipino, Japanese or Korean. After 9/11 two morons in AZ killed a Sheik because he wore a turban and they thought he was an Arab.