Across the Divide: What It Means to Be American

Guest post by Jinny So

This week, I’m hosting a guest post by my friend and fellow writer Jinny So. I’ve enjoyed her work; I hope you enjoy it too.

Trained as a lawyer, Jinny So has taught at a university in North Korea and led a science fiction and fantasy writing workshop in a U.S. federal prison. These days she homeschools her children, manages operations for a non-profit organization, and writes essays and speculative fiction on the side.

Thirteen years ago, I was sitting in a university cafeteria in North Korea. As a young American teacher brought in on a special volunteer visa, I knew I had to be careful about what I said. It wasn’t just my safety at stake—it was my students’ too. While we often had free-flowing conversations over bean sprout soup and rice imported from China, certain topics were always off-limits, especially politics or history.

When my students started talking about “the war when we defeated the Americans,” it took me several minutes to figure out how to respond. Honestly, most of that time was spent trying to understand what they were even referring to. Defeated the Americans? What war?

Then it clicked. They were talking about the Korean War.

Memories of stories I’d heard about that three-year war in the 1950s rushed to mind. My Korean grandfather had fled the communists and found refuge with the American army in the south; it’s even possible he met my American grandfather at the base there. The Americans had pushed the North Koreans nearly to the Chinese border, only to be driven back by waves of Chinese soldiers. The fighting eventually settled around the 38th parallel, where a heavily fortified demilitarized zone still marks the border between North Korea and South Korea.

But I couldn’t share any of this with my students. Instead, I sat in silence, listening to their state-sanctioned version of events, an uneasy realization settling in. Could two people really sit across from each other, sharing a meal, and yet hold completely opposite understandings of the same history?

I was young then.

I’ve since come to understand that divergent versions of history aren’t unique to North Korea; they exist everywhere, including my own country. I understood this starkly during the Ferguson protests over the killing of Michael Brown by Officer Darren Wilson. I was in law school then, and I remember how some saw it as a clear case of police brutality, while others believed the officer defended himself in a legitimate exercise of his authority. The facts of the incident were debated, but more strikingly, the meaning of those facts—the narrative surrounding justice, race, and authority in America—varied dramatically.

But why? Why was my school fracturing, friendships fraying, over which version of the story was the true one? Why did it matter that North Korea called what Americans refer to as the Korean War the “Fatherland Liberation War,” while South Korea named it the “June 25th Upheaval,” based upon the day the North Koreans invaded? What is it about competing national narratives that makes them so charged, that people are willing to fight, even kill, to defend them?

According to Anglo-Irish political scientist Benedict Anderson, a nation is an imagined community. It “is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.” In other words, a nation is a social construct created through shared beliefs, narratives, and symbols, where people who may never personally meet each other still feel a sense of belonging to a collective group; essentially, they “imagine” themselves as part of a larger community.

I like to operationalize things, so when I first read this definition, I tried to break it down. What exactly makes up this imagined community? Geography, yes. Political borders, of course. But overlaying the physical is a collective understanding of what it means to belong to a particular country. Being American means something different from being Ghanaian, Russian, or Argentinian. What does it mean? Well, that’s when we turn to history. We pick moments from the scatterplot of the past, magnify them, highlight their importance, and then draw lines between them to create a tale that tells us who we are.

National narratives are mainly built around key historical moments: revolutions, wars, and social movements that define the collective memory. These events are not merely facts; they are carefully constructed stories shaped and reshaped to strengthen a sense of national pride, unity, and purpose. Take the United States, for example. The story of the American Revolution is told as one of liberty, democracy, and the fight against tyranny, crafting the enduring image of the United States as a beacon of freedom and justice. This founding narrative has shaped the country’s identity as a land of opportunity and self-determination, even when people don’t agree that America has consistently promoted those values.

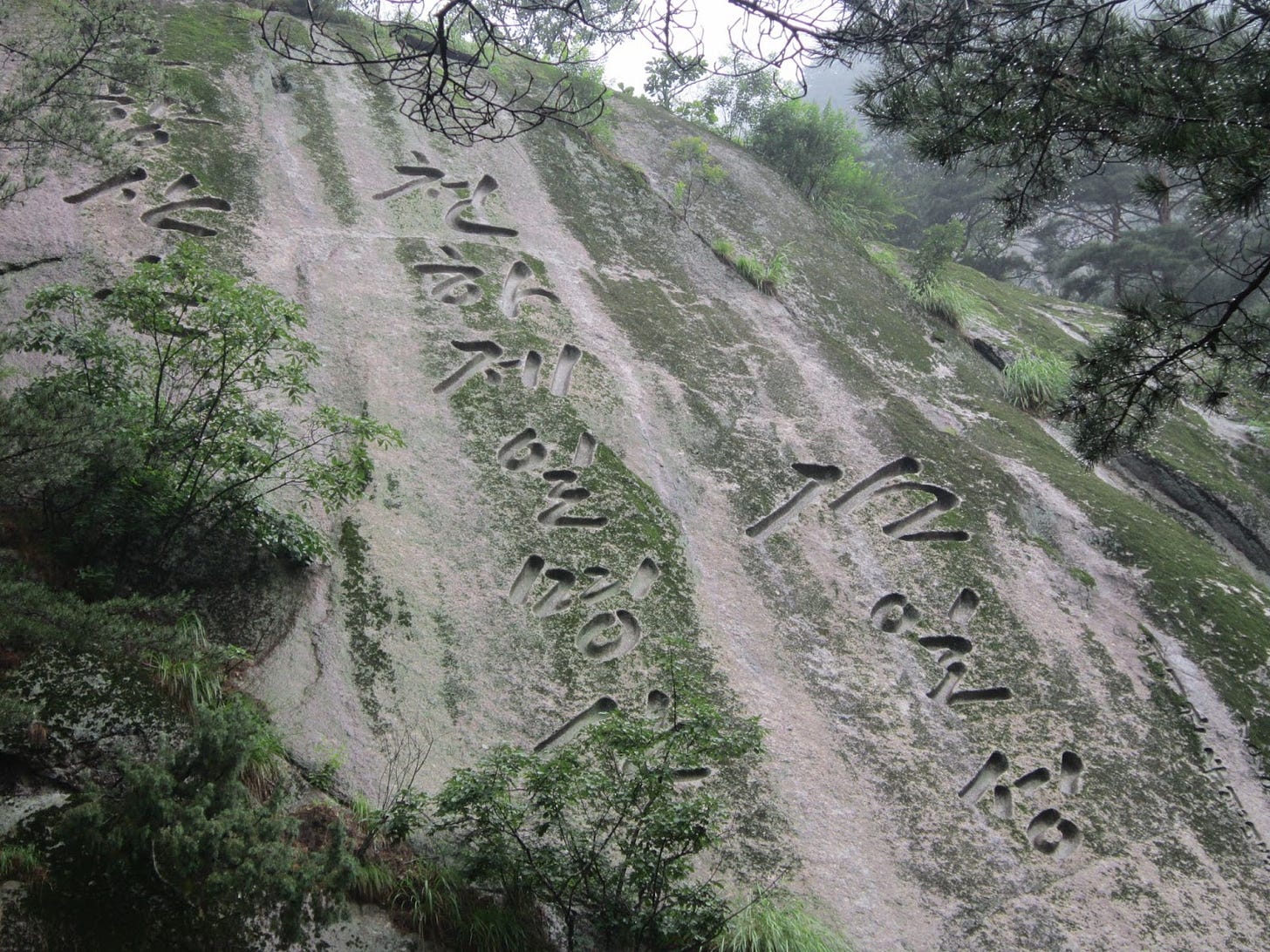

Over time, these stories embed themselves in the fabric of everyday life. They are passed down through school lessons, celebrated in national holidays, etched into public monuments, and woven into the rituals that define a nation’s culture. They give individuals a common framework to understand their place in the world, even if they have never directly experienced the events being commemorated.

The story of the American Civil Rights Movement is another prime example. Its themes of justice, equality, and moral progress resonate deeply across generations. For many, it is part of a narrative that highlights the nation’s capacity to confront its wrongs and expand freedom to all citizens, offering hope that America can continually improve. It influences how people see their role within the larger story of the country. The idea that America is a nation constantly striving toward justice encourages individuals to view themselves as part of a broader historical arc, one that bends toward the universal applicability of American values. These stories, whether of revolution or civil rights, become central to how citizens understand themselves, their values, and their responsibilities in shaping the nation’s future.

Looking back now, I realize my North Korean students had grown up with their own narrative too. For them, the Korean War was a righteous struggle, a moment of triumph in defending their homeland from foreign invaders. Their history textbooks, state-sponsored celebrations, and public monuments all reinforced this story. Just like in the U.S., their national identity had been built around a carefully constructed narrative, but one that stood in direct opposition to the one I had learned. We were looking at the same history, but from opposite sides of the line, each of us convinced that our version of events was the true one.

My husband and I once had an argument about locking the door when we left the house. I didn’t think it was necessary, trusting that we lived in the kind of safe neighborhood I’d always grown up in. “It’s fine,” I’d say, “nothing ever happens around here.” He, on the other hand, had been born on the South Side of Chicago, and found it difficult to shake the automatic habits of security in which he’d been raised.

The argument ballooned as we each championed our view of what a locked door meant. For me, it was an annoying, unnecessary hassle. I was always juggling the baby, my hands full, and the last thing I needed was to fumble for keys while trying to hoist a child. To him, it meant safety. Locking the door was second nature, something he’d been taught since childhood as a way to protect against the unexpected. It wasn’t just about convenience; it was about knowing that he had done everything in his power to keep his family safe.

Now, my husband also went to law school, so naturally, our instincts kicked in: we dragged the argument through multiple rounds of appeals. With no judge to settle it, it went on for years until our low-level demilitarized-zone-style conflict finally ended with my baby growing up, thus freeing my hands to grab keys without issue.

Though my husband and I eventually found a resolution, that argument often resurfaces in my mind when I consider how people interpret national events in such radically different ways. Just like our views on locking the door were shaped by our individual experiences, national events are interpreted differently depending on which narrative the interpreter is working within. In the same way my husband and I saw the same lock but attached different meanings to it, we all look back at the same scatterplot of historical facts and draw different conclusions, creating different stories to emphasize who we are as a nation.

Consider the Civil Rights Movement. I mentioned earlier that it’s part of a narrative that highlights the nation’s capacity to confront its wrongs and expand freedom to all citizens. This narrative views America as a unique place of freedom where the fight against government overreach has led to a continual broadening of individual rights. According to this narrative, America’s history is one of ongoing efforts to ensure that the freedoms and rights we correctly recognize as valuable are extended to everyone within its bounds.

While I’m not a practicing lawyer, I found myself diving into case law while writing this post, and I see a clear throughline—starting with Marbury v. Madison (1803), which established the principle that even the government must operate within the limits of the Constitution, to Gitlow v. New York (1925), where the Supreme Court first began applying portions of the Bill of Rights to the states, thereby restraining government overreach at both state and federal levels. This thread continues through landmark civil rights cases like Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which overturned state laws mandating racial segregation in public schools, and Loving v. Virginia (1967), which struck down bans on interracial marriage. These cases illustrate a clear arc: individual rights, once reserved for only a few, have been expanded to protect everyone from state overreach, reinforcing the notion that America is continually striving to realize its promise of liberty and justice for all.

However, there’s another narrative that picks out different moments from the same scatterplot of history and draws a much bleaker line, telling the story of an America built on oppression from its very foundations. This narrative highlights cases like Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), which denied citizenship and basic rights to African Americans, and Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which enshrined racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine. It points to United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), where the Court ruled that Indian immigrants could not become naturalized citizens because, although of “Caucasian” descent, they were not considered “white.” Then there’s Korematsu v. United States (1944), where the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II was upheld as constitutional.

If you’re looking at that story, you might read Shelby County v. Holder (2013) as a weakening of the Voting Rights Act to make it harder for marginalized communities to vote. If you’re looking at the expanded rights story, however, Shelby County might be seen as a necessary recalibration after decades of progress, reflecting confidence in a system that has grown more inclusive and fair over time. This case might suggest that protections enacted in the past had done their job, and that America had moved beyond the need for such oversight. The very same case, depending on the narrative you subscribe to, can either mean the erosion of hard-fought rights or the maturation of a democracy that has outgrown its more restrictive past.

These differing narratives are so charged precisely because they directly influence the real-world decisions we have to make. In the case of our garage door argument, whose perspective would ultimately decide whether it should be left unlocked? Mine, with my sense of safety based on past experience, or my husband’s, shaped by his upbringing and automatic instincts for security?

To be clear, disagreement isn’t inherently the issue. Debate and dissent are part of what makes democracy work. The real problem emerges when a national narrative starts to identify those within the nation as the enemy. When half of the country sees the other as a threat, the focus shifts from trying to find common ground to wanting the other side politically, if not actually, dead. This kind of division fractures the very foundation of a nation, turning fellow citizens into adversaries in a battle over whose vision of the country should prevail. At that point what was once a clash of ideas becomes a war for survival, with both sides convinced that the other’s victory spells the end of the country as they know it.

I can already hear the chorus of voices: but the other side really does want me dead. And I hear those voices, and can empathize. Vague appeals to unity or “coming together” don’t mean much to someone convinced the other side has already declared them the enemy and that they’re locked in a struggle for political survival.

So, what’s the solution? How do we build a robust national narrative that can hold us together? I found my answer in love and wit, namely a verse by American poet Edwin Markham:

“He drew a circle that shut me out-

Heretic, rebel, a thing to flout.

But love and I had the wit to win:

We drew a circle and took him In!”

Now the reason I started wanting to answer any of these questions I bring up in this blog post is because I care about my country, not only because I was born here, but because even someone like me can feel confident about participating in shaping its national story. That’s not something that’s possible everywhere. Sure, the government plays a role in shaping and promoting certain narratives, but not in the same monolithic way that we see in other places like North Korea. One of the things I love about this country so much is that anyone gets to contribute to the American narrative, as long as they can make it compelling enough to capture people’s attention and imagination.

And because I love this country of mine, I want it to have the best story moving forward. Drawing from that love, I turned to love and wit and began to imagine a way to bring everyone into the fold, differing narratives and all.

The very conflict we’ve endured over who we are as Americans, this ongoing struggle to define ourselves, is part of what makes us American. It’s part of our story, part of who we are. We’ve always been divided, and we’ve always disagreed whether it was the Tories versus the Patriots, North versus South, or liberals versus conservatives. But we don’t have to let it end in violence or hatred this time. We’ve been here before, standing on the edge of division, but what defines us as a nation isn’t just the division itself, it’s how we choose to respond to it. We don’t have to be like Vichy France, where the right hated the left so much that they were willing to throw France to the Nazis rather than work things out with the left. We don’t have to be like Bolshevik Russia, where the left hated the right so much that they were willing to overthrow the entire government and plunge the country into civil war rather than find a way to share power. Neither of those outcomes led to anything but devastation for everyone involved.

We also don’t have to be like Korea, which remains divorced to this day.

That’s my offering to the American narrative. Be whatever you are politically. Don’t change that. Don’t try to convert others. Instead, accept that we’ll always disagree with each other, and love your neighbor anyway. I may not have the prophetic vision of Martin Luther King Jr., who saw “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners sitting together at the table of brotherhood,” but I can offer this: to be truly American is to love another American across the political divide. The best American is the one who bridges that gap with the most generosity and grace.

If you’re interested in more, check out Red Zone Son, Jinny So’s science fiction thriller on race, religion, and politics in a near-future divided America.

This was very nice. Thank you. I'll check out your book. Where else do you write?

Together with your example- the U.S retreating 3 times off! The Peninsula to their ships, - important watersheds in the 20th century read differently from peoples' present passions. The 40 hour week was so hotly contested by laborers and plutocrats that FdR's secretary of labor adopted the Soviet 40 hours out of some idea that the USSR had some success with that schedule, and established t by fiat. Now, of course you can believe unionists saying the weekend was hard-won. If it had come up for debate night never have been accomplished because of the passions involved. The same way citizens going fishing are a monument to that moment, the one out of 6 americans who work in government are a monument to good intentions.