This month, like I did in December, I'm posting here super-short reviews of and thoughts on some books I've read in the last few months but haven't mentioned yet. In December, I majored on novels; now, I'll major on history.

The Cherokee Syllabary: Writing the People's Perseverance, by Ellen Cushman

This's a very interesting linguistic and historical analysis of the Cherokee syllabary and its place in tribal culture. While Cushman is clearly a cheerleader for Cherokee culture in its own right, her analysis shows the syllabary has unique value, on top of being a symbol and vehicle for tribal culture.

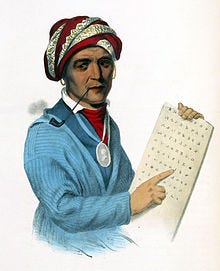

The Cherokee syllabary was invented by one Cherokee man, Sequoyah - by himself - around 1821. Having realized that written English was a powerful tool for American culture, he decided that the Cherokee needed their own written language, and spent years developing a good system to write it. He decided that the best system would be a syllabary, where each symbol represents a syllable (rather than a single sound, like the English alphabet; or a whole word, like Chinese characters). He developed it and designed the characters by himself. After he and his daughter demonstrated it to the Cherokee tribal council (they dictated him a text while she was out of the room; then they called her in, had him leave, and she read it aloud), the syllabary spread like wildfire. Just a few years later, almost every Cherokee was literate, Sequoyah was working on getting a printing press in Cherokee, and an American missionary was explaining to his missions society that they had to print Cherokee works in the syllabary because no one would read them if they used any other alphabet.

Since then, until the modern era, it's continued to be a mainstay of Cherokee culture. Cushman tells multiple stories of its persistence and Cherokees' dedication to it.

Also, she argues - with evidence - that the Cherokee language lends itself uniquely to a syllabary. Most words are compound words, where each syllable has a unique meaning that contributes uniquely to the overall meaning. While the word might still translate as one English word, it's assembled like a phrase. So, each of the 85 characters of the syllabary can be seen as repesenting one "word". Of course, these 85 words may have different meanings in different contexts - but they're still very meaningful units. Cushman confirms this analysis by interviews with and accounts from fluent Cherokee speakers.

I'm even more fascinated now by the syllabary and by Sequoyah as a person. We have other stories of people designing alphabets for previously-unwritten languages, such as Cyril and Methodius - but is there any other illiterate person who designed a writing system for his own language? And on top of that feat, Sequoyah fit it well to his language, in ways that English-speaking onlookers didn't even realize!

Massacre at Mountain Meadows, by Ronald Walker

In 1857, as the tensions between the Mormons in Utah and the American government were building towards the Mormon War (based in part on polygamy, in part on their insular theocratic authority structure, and in part on prejudice) - and as frequent wagon trains were moving across Utah to California - the Mormon settlers in southern Utah (acting on their own, Walker and his coauthors show) massacred one California-bound wagon train. This book explores that massacre and the events leading up to it.

Walker and his coauthors ably paint the tensions as they were on the ground, as well as the hardscrabble circumstances of the near-desert Mormon settlements in southern Utah. It's a vivid depiction of a community on the edge in multiple senses, trying both to survive and to prepare for an oncoming war. A hostile US army was en route just beyond the mountains, they didn't know how to meet it, but they knew they were ill-prepared. In the midst of this tension, we hear how these otherwise-moral settlers were stirred up to such violence - and how, unsurprisingly, it didn't go as smoothly as they'd assumed.

I picked up this book not just for the sequence of events, but for a look at the psychology of the people involved, and Walker delivered what I'd hoped for. We see how a sense of being besieged by enemies, and seeing this wagon train as enemies, led to violence. And then, we see how one enormity led to more to cover it up, only to eventually fail.

American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment, by Gerard N. Magliocca

John Bingham was a prominent Republican in Congress through the Civil War and Reconstruction, lead prosecutor during Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial, and - most significantly - the author of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment. As he called it, it was an amendment "to enforce the Bill of Rights" against the states.

This's a short biography. Reading between the lines, this's because unfortunately Bingham didn't leave many papers exposing his internal life, and unfortunately never rose higher than the House of Representatives - in part because he wasn't that great a politician. Although he sometimes modulated his beliefs for the public mood, he didn't show much talent at actually playing the game of interpersonal politics.

But, he lived at an era where he could rise on his copious citations, impassioned rhetoric, and strong anti-racism. And, he rose on it as a charter member of the Republican Party, to the Joint Committee on Reconstruction. There, he insisted that the Constitution did need to be amended. It was designed to ensure that the formerly-Confederate states now readmitted to the Union wouldn't discriminate against the newly-freed Black people. Bingham seized on that need and insisted that it be written in sweeping terms that referenced the original Bill of Rights, and would apply to anyone not just to freedmen. (In fact, this's one of the first references to the first ten Amendments as the "Bill of Rights.") The Constitution and Bill of Rights was wonderful, he said; it just needed to keep the states from violating it.

Bingham's work sadly failed, as the South rose up against Reconstruction, the North made its peace with "Jim Crow," and the Supreme Court read the Fourteenth Amendment into a nullity. Bingham himself left Congress and retired as Ambassador to Japan, where he stopped speaking about civil rights. But then, after Bingham's death, his legacy came back as the Supreme Court again interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment - like he'd designed it - to "incorporate" the Bill of Rights against the states. Whenever someone claims a state action infringes their Constitutional rights, they're invoking Bingham's worthy legacy.

The Pseudoscience Wars: Immanuel Velikovsky and the Birth of the Modern Fringe, by Michael D. Gordin

Immanuel Velikovsky, in the mid-twentieth century, published his unique psychological-historical-astronomical theory that the planet Venus was birthed from Jupiter as a comet, made close passes by Earth causing many catastrophes in historical times, and then humanity repressed the memories and only recorded them symbolically as myths. There are no generally-acknowledged mechanisms for any of this.

Nonetheless, Velikovsky persisted, crying persecution upon being rejected by the scientific establishment, and eventually gaining a countercultural following in the 70's. This book analyzes the response to his theories and argues that he gave birth to modern American pseudoscience movements. On the one hand, he paved the way and showed that there was a popular audience for scientific-sounding theories outside the scientific establishment; on the other hand, many prominent figures in later pseudoscience movements actually started out in Velikovsky's following, and in some cases split off when they tried to develop his theories in other directions.

This's an interesting story, but limited. The author doesn't try to offer a cohesive definition of pseudoscience except on the societal level, he doesn't attempt a comprehensive survey of modern pseudoscience movements, and he doesn't advance any recommendations for how people should respond to pseudoscience. He writes a history of one aspect (the main aspect, he argues) of the birth of modern pseudoscience. I enjoyed reading it, but I wish it was more - it reads like the first part of a story. We have the problem, and we have some initial attempts (the university professors who responded to Velikovsky) that failed to face it. But what shall come next? I can't answer, and this author doesn't attempt to either.

Oof. The fit of the syllabary cannot help being oversold. The evidence you cite is not helping, to say the least: this description would fit if every syllable was a morpheme, which is sort-of almost a thing in Chinese and normally used to explain why syllable-correlated ideographics fit Chinese!

What really helps with syllabaries is strong limitations on syllable structure: if you only allow CV (or CV and CVN, like Japanese), syllabaries are a good fit (although allowing onsetless is not a problem), if your syllable structure is more like (C(C(C)))V(C(C)) - as, say, in Russian or English - they are a bad fit. Linear B is a good example of using a syllabary for a language it was a painfully bad fit for, namely, Greek which had, to simplify, (C(C))V(C)(s) structure.

And Cherokee syllabary seems to be a bad fit on this axis: judging from Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cherokee_syllabary#Detailed_considerations), the language: does have consonantal clusters; does have several possible consonants in coda, of which only s is reflected; and has tones not reflected in the syllabary.

I may have to pick up the Massacre of Mountain Meadows. I know a lot about it (my great great grandfather was out of town at the time or I'm sure he would have participated), but it's mostly through osmosis. Reading an organized account would probably be useful.

On the Pseudoscience Wars, did you pick that up after reading my review or was did you come across it independently?