Imagine no possessions

I wonder if you can

No need for greed or hunger

A brotherhood of man

Imagine all the people sharin' all the world

Yoo, hoo, oo-oo-- John Lennon, "Imagine," 1971 AD

Under thy rule what trace may yet remain

With us of guilt, shall vanish from the earth

Leaving it free for ever from alarm...

The whole world will he rule, now set at peace...

The teeming she-goats without call come home,

The flocks by lions shall be scared no more,

No more by serpents and by poison plants...-- Vergil, Eclogue 4, 42 BC

I

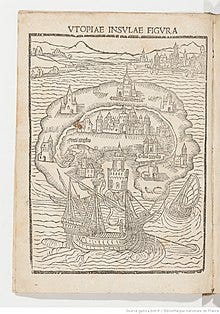

Imagine - and you aren’t the first to imagine it - a world where we can all live together in peace and spend our time in leisure however we want. Where we can live in plenty without toil or scarcity. Where no one is selfish, and everyone is friends.

It's an ancient dream that still calls to us just like it called to people long ago. Cory Doctorow, in his 2017 novel Walkaway, isn't the first or second or most detailed to picture it, but he offers a novel angle on the vision. He shows his new utopia not at war with the current state of things, but - despite staunch opposition - triumphing simply because it's so much better that people "walk away" to it. And, the whole picture seems plausible. It feels like, if you start living now like you're in it, right now could maybe start "the first days of a better world."

The world of Walkaway isn't the same as our own, but it's extrapolated from here. The economy seems to be in permanent depression. The economy is under the control of large corporations owned by multibillionaire "zottas," with individuals forced to take out heavy college loans to chase ever-scarcer and ever-more-precarious jobs. Amid this, more and more people are choosing to "walk away" from mainstream society to live in their own anarchist communes.

The plot follows three "walkaways": Natalie "Iceweasel", the daughter of a zotta who dislikes her family and thinks their life hollow; her friend Hubert "Etcetera" who "goes walkaway" with her; and their new friend Limpopo, the informal leader of a walkaway B&B whom they meet their first day. We see a proposal to manage the B&B by a formalized reputation economy get rejected by Limpopo "forking" things and walking away, taking most of the maintainers with her just like a free software fork. We see cognitive scientists go walkaway when they're on the verge of brain upload technology, fearing lest the zottas have sole access to this immortality. We see their research leap ahead in a walkaway community, to where they actually upload a person to a computer for the first time, only to have the lab site destroyed by "default society" through its police. Our protagonists simply walk away again mid-fight, and uploaded Dis emails herself elsewhere. We see, after many trials, Limpopo get arrested and Iceweasel kidnapped by her family. But - after fruitless arguing with her father - Iceweasel escapes, gives up her trust fund one more time, and reunites with her friends.

Then, Doctorow's narration skips ahead in time. A few decades later, walkaway society has essentially triumphed, and "Default" society is fighting smaller and smaller rearguard actions. All of this is delivered in narration as Doctorow moves forward to a character-based climax. The guards at Limpopo's prison having pulled out, the prisoners (mostly nonviolent, and even the others ready to join in) declare their new commune part of walkaway society. "Default"'s attempt to retake it is forestalled by walkaways convincing the police to desert, Iceweasel's father risks everything to talk to his daughter once more - fruitlessly, for neither will compromise or sees any value in the other's lifestyle - and our friends all reunite in what is clearly a better world dawning.

II

We've heard utopian dreaming before; we've seen utopian anarchists before. Doctorow's twist is to reimagine them after the fashion of present-day internet communities. As he put it in an interview, "The thing that free and open-source software has given us is the ability to coordinate ourselves very efficiently without having to put up with a lot of hierarchy... What would it be like to build skyscrapers the way we make encyclopedias in the 21st century?"

This links his vision of the future invitingly to the present. It feels like we're already almost "the first days of a better world." And, it makes the whole noble vision feel almost plausible. It might not be the typical model of human nature, but we've seen some things work like this already.

Doctorow flatly denies that typical model of human nature. He has one walkaway describe the tragedy of the commons as "the idea that it's human nature to kid yourself and take the last cookie... so he had better be the most lavishly self-deluded of all, the most prolific taker of cookies." Hubert agrees: "Everyone knows that that bastard is on the way, so they might as well be that bastard" (p. 45; all page numbers are from the Kindle edition). Limpopo will later contrast, "The stories you tell come true... If you assume people are okay, you live a much happier life" (p. 80).

This might sound like Marx's claim that human nature is completely malleable. But, we can - again - almost see this new idea played out in the free software movement. Unpaid volunteers have built an operating system and an encyclopedia; how can a selfish model of human nature explain that? Doctorow explains on his blog, "Most people like building things together. As long as the two elements of building and sociality are present, you do not need to obsess too much about incentives." What matters instead, he says, are the technologies for cooperation.

And, he says further, we also see this helpfulness elsewhere: "The truth of humanity under conditions of crisis" is that "people rise brilliantly to the occasion, digging their neighbors out of the rubble, rushing to give blood, opening their homes to strangers." He references Rebecca Solnit's book A Paradise Built in Hell, which I haven't read but is now on my to-read list, about how this sort of altruism comes to the fore in real-world disasters when the outside world suddenly isn't relevant.

Suddenly, he makes utopia seem almost in our grasp.

III

But walkaway society owes more to the free software movement than just its culture. When Doctorow talks about building skyscrapers like Wikipedia, he has his characters almost literally do that. He never outright says they have full-scale matter duplicators, but he says they have automated factories in back rooms which seem to print out anything just as easily as a modern 3D printer prints plastic. Take these examples of what're essentially matter duplicators:

It had taken Limpopo a while to get the idea that food was applied chemistry and humans were shitty lab techs, but after John Henry splits with automat systems, even she agreed that the B&B produced the best food with minimum human intervention... The menu evolved through the day, depending on the feedstocks visitors brought. Limpopo nibbled around the edges, moving from one red light to the next, till they went green, developing a kind of sixth sense about the next red zone, logging more than her share of work units... There were enough perishables that the B&B declared a jubilee and put together an afternoon tea course.

-- (p. 58-59). (All page numbers are from the Kindle edition.)

"Easiest way to get started is to ask for an inventory of traveling stuff - warm-weather, cold-weather, wet-weather, shelter, food, first aid - cross-referenced by available feedstocks and rated by popularity."

...They whipped through options quickly and hit commit and marveled at the timers. "Six hours?" the girl said. "Seriously?"

"You can do it in less," Limpopo said, "but this rate allows us to use feedstock with more impurities by adding error-correction passes."

-- (p. 83, 87).

More than Doctorow admits, the walkaways' anarchist society depends on these duplicators. With the duplicator, Limpopo's Belt & Braces bed-and-breakfast can print out breakfast and lunch and dinner and new clothes and walls at that. Without it, it'd would require a whole lot of sous-chefs at stoves actually working out the vision instead of eating and socializing. And other things would be worse than that - cooking's somewhere anyone can help. (Well, okay, most anyone. Don't ask me about my younger self in the kitchen.)

Point is, there're other things where the average walkaway would be totally useless. For example, take manufacturing advanced medicines. With the duplicator, they just print them off (pp. 75, 211, 489). Without the duplicator... well, we’ve heard how mRNA vaccines require scarce microfluidics machines to consistently encapsulate the RNA in nanoparticles. Considering next to no one can make one or run it in this world, I doubt a bunch of walkaways could do it without duplicators. Fortunately, in Doctorow's world, they do have a duplicator which they can set to (somehow) make RNA nanoparticles just as easily as sleds or breakfast.

On top of that, the duplicators can run off solar power and local junk. We do hear of a "feedstock plant" (p. 13) and branded feedstock (p. 15), but when we actually see drones bringing in the feedstock it's a "load of textiles, metals, and plastics, the sad remnants of collapsed industry" (p. 87). It can also be abandoned buildings (p. 111) or dead bodies (p. 161) or "stuff" (p. 148). (The duplicators themselves seem to be among these "sad remnants of collapsed industry." We never hear of walkaways making them, and at least once (p. 13) it's specifically stated that they were abandoned by Default society and repurposed.) All this feedstock can, apparently, make anything including food (p. 296). We never hear outright they can transmute elements, but aside from one mention of long-distance transport of "high-quality plastics" (p. 433) in practice any feedstock seems able to fulfill all purposes. These versatile matter duplicators liberate the walkaways from so many constraints.

All this, of course, is far different from the real-world 3D printers and fab labs which Doctorow's actual terms imply. My friend has a 3D printer; he's made some fun things with it. He runs it off a specific sort of plastic feedstock, and he gets a specific sort of output. He could vary the mix if he wants to make something more flexible, and he could probably stretch as far as clothes if he wanted to - though if he did, Limpopo's six-hour wait would be very realistic. But food and medicines are right out, and trying to run off junk would break the machine. And I really wouldn't want to live in a building built by it.

In the free software movement today, most of the people who use Linux or LibreOffice or Apache never contribute to the code. Most of them probably wouldn't have the least idea how to do so. And, most of them never pay the people who write it. So be it; that's not a problem. One person in however many wants to write code - perhaps for fun; perhaps (as Doctorow implies and puts in Limpopo's mouth) to contribute to the common cause. Even if it's just one guy in Nebraska, if he builds something that works, computers can copy his efforts across the world.

The small far-right site Conservapedia once called the free software movement "inherently communist" and "shun[ning] the idea of payment and cost." Their habit of (to put it charitably) vigorous overpoliticization was in play here. But they're not completely wrong. In software, this Communism works. If most people laze around, no problem; the people who work can cover everyone. If people aren't interested in doing the same assembly-line work day after day, no problem; once they do it once, computers can duplicate it however many times are needed. If matter duplicators can make everything like software, maybe Communism really can work!

But without duplicators... well, we know the story of the real-world anarchist communes. For example, the famous Oneida Community was founded in 1848 amid millennialist utopian hopes; it grew from 87 to 172 by two years later, but growth swiftly leveled off. In 1879, after their charismatic founder fled the country ahead of statutory rape charges, they abandoned their "complex marriage". In 1881, they reincorporated a capitalist joint stock company. Oneida was unusually successful. Usually, they evaporated much faster without reinventing themselves as capitalists.

Modern or near-future utopians would have things even more difficult than Oneida. Oneida always used money and participated in the broader economy. Also, it was in a favorable time period - it could produce or buy most luxuries of life; modern utopians who forswear the economy wouldn't be able to. Without duplicators, Default society would have a lot more comforts to lure people back with. These duplicator-less walkaways would collapse just like the real-world utopian communes, and their utopian dreams would perish with them.

Or maybe there'll be a Communist revolution that gets people to all work together and establish a utopia anyway. I mean, it could happen this time!

IV

But even with duplicators, walkaway society can't duplicate everything. In George O. Smith's 1945 Venus Equilateral short stories, which also include duplicators, we see a doctor using it to test a new treatment. He duplicates the patient, tries the surgery on the duplicate, and - when it works - repeats it on the original. Obvious ethical concerns aside, there's one big point here the duplicator doesn't help: you still need to find the doctor. You can't duplicate medical education into his head. Without it... well, several thousand duplicated bodies might get an amateur some competence, but it might take about as long as old-style medical school.

What we actually see with the walkaways - when a police attack causes mass casualties - is a lot more traditional. Someone wakes up several doctors who went walkaway, who videoconference to the mass casualty site to instruct semi-trained volunteers in treating the victims. Anything they need is, of course, printed on the duplicator.

Of course, not everything can be treated by semi-trained volunteers - but telemedicine is a growing field, and it can already do a lot. The bigger problem is that telemedicine still depends on the real, trained doctor. He has to have the training; he has to wake up in the middle of the night to use it. Among the walkaways, he does it for free. Of course there'll be doctors willing to do that for a bit. We see it all the time nowadays, such as in the disasters Doctorow cites. Some of them will be willing to do it for a while, just like we see some doctors working for low pay in Tricare or the third world. But will there be enough willing to do it for long enough? We’ve seen enough nurses resigning from exhaustion in the recent pandemic that I can't assume there will be.

(For another example, if an acquaintance has a relative die, I know a number of people who'd gladly bring over a casserole or something to help with her grief. But if her grief turns into long-term depression, we probably won't be bringing casseroles ever day for years.)

And even more disturbingly, who will replace the walkaway doctors when they finally give up? Doctorow's book ends just as the second generation of this new society is growing up. Will we see just as many people willing to go to medical school in that next generation? As Smith puts it in Venus Equilateral right after duplicators have crashed the old economy:

Then what about the automobile boys? Has anyone ever tried to make his own automobile? Can you see yourself trusting a homemade flier? On the other hand, why should an aeronautical engineer exist. Study is difficult, and study alone is not sufficient. It takes years of practical experience to make a good aeronautical engineer. If your man can push buttons for his living, why shouldn't he relax?

Perhaps "we are witnessing the evolution of the human race," as Suzanne Collins put in an optimistic character's mouth in the denouement of Mockingjay. Perhaps, as optimists have said from Virgil to Marx, once the present "default society" is done away with, we'll see people choosing to study hard and take on the roles necessary for society. I can see that for a bed-and-breakfast. I can even see an unusual someone going through all of medical school for fun. As one of Smith's characters says, "Someone will find pleasure in digging latrines if you look for him hard enough."

But how many people will do that? Sure, maybe one person will study enough to be a licensed engineer, and he can put out the duplicator designs for everyone. But will there be enough doctors for everyone who needs medical attention? Maybe there's more than one reason why the post-replicator world of Star Trek eventually introduces "Emergency Medical Holograms": maybe there just aren't enough human doctors.

Okay, Doctorow does show us a backup option: the backups. People uploaded to AI's were born and trained in the "default society." If nobody studies medicine (or something else) in the new walkaway world, there'll still be at least one AI who knows it, and the AI can duplicate itself. Maybe they'll be benevolent. Or maybe not, and that new technocratic gerontocracy would at least be really fun to read about.

V

Still, given the duplicators, the walkaways' critique of default society is completely correct.

Limpopo describes her past growing up in Default: "Mom and Dad were all over the idea of me going to uni. They'd both gotten degrees and swore it had been worth it, though they would owe money until they died, and neither one had ever held a job for more than a couple years... Neither of them had a pension and they'd need me to feed them once they were too old to get another job after the next layoff. (p. 346)."

With duplicators that can create food out of (apparently) whatever's lying around, there is no excuse for people starving. With duplicators that can create clothes, there is no excuse for people going in rags. That happens now because - at the least - feeding and clothing people requires effort. But with the sort of duplicators that exist in the novel, it no longer does. Default society also has duplicators and could do this. It's implied that'd be patent infringement because the duplicator recordings are patented (see Limpopo's history with textile makefiles on p. 345). The one time we hear a zotta defending himself, he says that changing society would "take away everything we have" and "destroy everything" (p. 290). But, that's at least approaching the old parody of libertarianism: if one person owned everything, could he made everyone else slaves? If trademarks can keep back such potential - if there's ever a time for eminent domain to open things for public use, it's then.

It's no surprise that pretty much everyone in the novel recognizes this eventually. It's no surprise that the walkaways can even convince policemen sent to arrest them to instead join them. Default society could do this without any effort, so when it fails to do it, it's morally wrong. Given duplicators, everything else is obvious.

Now, some other science fiction writers have posited that some sort of typical economy will survive duplicators. Neal Stephenson takes the more realistic route in his Diamond Age by restricting duplicators' feedstock: they can't break down random junk. So, their special semi-liquid feedstock is piped to each home and (unsurprisingly) metered and billed through typical economic systems.

The novella "Business As Usual, During Alterations", by Ralph Williams, posits more implausibly that "We'll sell diversity," and "Engineers, draftsmen, designers; we need about six times as many as we have" to make the designs for duplicators to duplicate. But with the modern internet to share designs, as Doctorow's walkways show, there's no need to sell the diversity because it's already there free for the taking.

Venus Equilateral gestures toward a new post-duplicator economy built around expertise and intangibles, but it never describes it in detail. What it does hammer home, though - also shown in Diamond Age - is that there's a new baseline: even amid the immediate economic collapse, "not one of them is starving, not one of them is unclothed, and not one of them is going without the luxuries of life." That's what the Walkaway zottas are preventing; that's why the walkaways' critique of their society is fully deserved.

This might seem like an about-face from my prior point. I agree that the economy can't just be thrown away; there needs to be some way to reward investments and expertise which can't be left to volunteers. But there needs to be some other way besides making everyone work on pain of starvation just so as to motivate a few people to study and become experts. You can't found society on something that cruel.

VI

We know exactly what the walkaways stand for in their nonviolent revolution. Anyone can look at their communes and see. They advertise "the first days of a better world": when they triumph - as we see toward the end of the book - the world will be like this.

Alister MacQuarrie pointed out that "The revolutionary is everywhere in pop culture, but... the heroic rebel on screen is often very evasive about the principles behind their actions." For example, in Star Wars, the heroes "fight to restore the Old Republic. Yet nowhere in the films is it ever explained what the republic actually stands for." Similarly, in Hunger Games, the finally-triumphant rebels vote to sentence the old regime's children to the games. All we can say is "The Empires of fiction are bad because they do bad things to us."

The walkaways avoid this. In-universe, this's a credit to them as activists; out-of-universe, it's a credit to Doctorow as a writer. They clearly and inarguably stand against materialism (p. 84), for the value of every human (p. 63), for social equality (p. 135), for free communication (p. 112), and for helping others (p. 414). Their agreement on this pervades the book; the references I've given are just a few of many. Anyone who cares to look, in universe or out, will know their principles and ideology.

Or, would they know exactly? Walkaway society isn't quite a monoculture; we see some differences between the Belt&Braces, Walkaway U, the Mohawks, the Adirondack retirees, and others. For example, some "households" formalize "reputation economies" and some don't (p. 414). But there're many commonalities as well, from the disdain of possessions to the welcoming of strangers to the onsen baths to the frank talk of bodily functions to the absence of mention of religion. This near-monoculture is plausible, given how they're all talking on the Internet. But how much of this monoculture is part of their core ideology?

This raises the question: how much would walkaways impose on others? Suppose someone does care about his possessions, or doesn't care for the onsen baths, or does preach a religion. In the modern world - in Default society - there're established procedures; this person would have his rights. In walkaway society, which has cast off Default's laws and traditions, what would happen? All the duplicators described are communal, owned by the household - would such an unpopular person get second-class access (or worse) to them? There're rumors of problems during the timeskip, but it seems there's still no clear path to deal with them:

Some communities never gelled, became ghost towns within months of being established. Sometimes worse things happened. There were dark stories about rapes, murder sprees, cults of personality where charismatic sociopaths brainwashed hordes into doing their bidding. There’d been a mass-suicide, or so they said. Everyone argued about whether these stories were real, minimized by credulous walkaways or stoked to a fever pitch by default psy ops. -- (p. 444)

We've seen any number of cases of modern real-world communes trying to handle these sorts of disputes. Some of them do it better, some worse - but this often shows the use of some sort of procedure rather than trying to figure things out on the spot while tensions are high.

It could all work out; Limpopo leads an exodus from the Belt&Braces rather than kick out a minority who insist on instituting a reputation economy. I expect she'd accommodate anti-onsenists or evangelists at least that well. Yet, her decision faced opposition even at the time from her fellow walkaways.

Some might argue we can look at the open source community (again) as a model. For example, it's arguably slightly biased against women who advertise their gender, but not against women in general. This doesn't reassure me. Designing software with someone is much more limited interaction than living next door to someone (let alone closer). And, sharing a duplicator with other people - sharing your access to everything - demands even closer interaction than being neighbors or perhaps roommates in the modern world. In the open-source community, if debate breaks down, you can take your own computer and code your own thing. In walkaway society, unless you somehow get your own duplicator, you can't do that. If duplicator time is in high demand, you can't get out of conflict with other people - and the book doesn't show us any clear system to solve that.

Were this real, I'd be glad to know what the prophesied better world will look like. I'd be happy for a lot of its features. But I'd still be concerned for those who don't fit in somehow.

VII

Doctorow has a noble dream. It's a version of the same noble dream prophets and minstrels have been singing throughout history, and it's no worse for its antiquity. The great story lends even more greatness to his writing, as Dorothy Sayers said about retellings of the life of Jesus.

And, like many other dreamers, Doctorow is certain what's keeping the world from that noble dream: inadequate coordination technology that's only recently been fixed, and the false story of the Tragedy of the Commons. Whether the story's false or true, I agree that's what's keeping us from it.

Unfortunately, his solution won't work either. In the end, I need to deny his version of the malleability of human nature just like Marx's. At least until we actually have the duplicators he puts in his novel – until we can actually run physical manufacturing and everything else like free software – human nature isn't malleable enough over a large enough population to run society on the unselfish New Soviet Man or New Walkaway Man. And even if we could, other dynamics like the cost of expertise or cultural enmities would also need to be changed in this new sort of person; I don't see Doctorow even talking about those.

In fact (I note on this Easter weekend), Paul the Apostle frankly talked about how a Utopia - or to use his words, the Kingdom of Heaven - couldn’t be built without people having changed hearts. And that level of change, he said, couldn’t come from anywhere except God Himself. Whatever you think of the methods of change he recommended, he got right the scale of change needed.

Still, I can't fault Doctorow. Society needs dreamers like him calling us to climb to the stars and fill in the strip-mined disasters of the present. We may not attain the stars. It may be hard to even reach the moon. But we must accept the challenge of going there – not because it is easy, but because it is hard.

Doctorow's world didn't strike me as very utopian. I have books that I love and reread repeatedly, some of which are out of print and could not easily be replaced. I have framed original art on my walls. One of the incidents in Doctorow's story makes it clear that there is no reliable security of possession in walkaway society, and that there is simply Nothing To Be Done when things are taken away, because walkaway society does not value "things." That strikes me as an inhumanity that I would be desperately eager to avoid. There is no peace in a society where I am not permitted to have my own personal treasures.

Well, that would be kind of a long answer.

Rather than take up space here, let me mention that the review site Black Gate has my review of Courtship Rite in their queue for publication sometime this month; that will tell you a lot of what I think about it.

In brief, though, Courtship Rite is my favorite science fiction novel, and one of my favorite novels of any genre or era. It was one of those books I just fell into at first reading. After my review comes out, I'm quite willing to discuss it if you care to.