When I was younger, I read one kids' adventure series where our young protagonists fight magic monsters in the first book. That's fairly common in kids' adventure books. What was less common about this series is that after the first book, magic never shows up again. It's only even mentioned one time. We only get normal human problems and enemies.

This's probably a more extreme example, but it's a surprisingly common phenomenon. TVTropes calls something like this "Early-Installment Weirdness." Their discussion of it is more geared toward TV series, and individual details of character or setting changing (such as, to take a non-TV example, the location of Watson's wound in Sherlock Holmes.) That can make sense for their purposes. But, this dynamic shows up in book series as well, and it can affect the shape and feel of the story rather than just details.

When it shows up like this, "early installment weirdness" is a sign that the author hasn't completely planned out his story from beginning to end as a unit. Sometimes, that happens. Sometimes it's for market reasons; sometimes it's because the author didn't anticipate where the story would take him.

And when it does happen, it can be interesting to study.

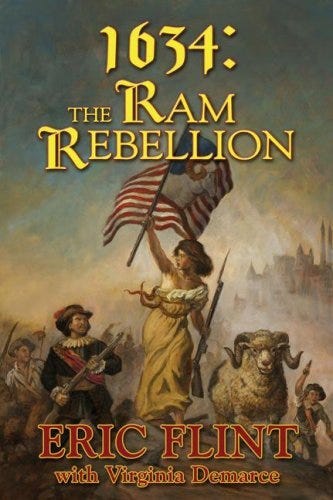

For example, take Eric Flint's 1632 series (which I recently praised for how it handles background characters). The first book (1632) does treat history respectfully, but in a somewhat fictionalized way - for example, after the town of Grantville is transported from 1990's West Virginia into Germany amid the Thirty Years' War, the town’s inhabitants interact with the fictitious Imperial City of Badenburg. Later on, our protagonists hear someone reference common knowledge that Shakespeare's plays were written by the Earl of Oxford.1

However, after this first book was published, a community of fans developed dedicated to historical accuracy and tracking down every subtle detail that could be used in the books. They've tracked down myriads of real cities and towns and artists. Eric Flint and his coauthors haven't decreed any official retcons, but imaginary Badenburg has never been mentioned again, and Oxford's authorship of Shakespeare has only been raised as a joke. The series has turned into something different, less "pulpy," and much more historically detailed. These sidesteps in the first volume are left behind as "early installment weirdness." There are some characters changing along with this; most notably, the former mine owner John Simpson reveals new depths and motivations as he changes from antagonist to ally. But by far the biggest shift is in tone

.For another example, the kids' adventure series I mentioned at the beginning is Ranger's Apprentice, by John Flanagan. In the first book, after a decently-done training arc, our protagonists fight magical monsters that are under the control of an evil wizard. But the magic vanishes before the second book, throughout the rest of the series they fight ordinary human enemies, and magic is never mentioned. At one point, we even see someone who's falsely pretending to be a wizard. Meanwhile, the world around our characters gradually solidifies from a vague unmapped fantasyland to something very close to the map of Europe. Again, the first book is never retconned - it's never stated that magic doesn't exist. But then, it's never mentioned at all except for one acknowledgement that very occasionally someone claiming to be a wizard will be a real wizard. The first volume is, again, left behind as "early installment weirdness."

Or, take Tolkien's Middle-Earth. The Hobbit is an episodic children's novel focused on the character growth of Bilbo, with most of the Dwarves interchangeable with hardly any personal traits, and with a narrator frequently dropping side comments to the readers. Its sequel, Lord of the Rings, is a three-volume epic with a more elevated narrative tone, well-developed characters, and moral concerns playing a leading role. There isn't entirely a sharp break; The Hobbit introduces near the end a morally-focused plot arc around the disposition of the treasure they've retrieved, and the start of Lord of the Rings opens in the Shire with a mostly-lighthearted adventure. But, the break in tone is extremely real.

Are these changes partway through the series - leaving behind "early installment weirdness" - a good thing?

It's not ideal for the overall story of the series. A series should, in a real sense, tell a complete story, without changes in the world in the middle. (Unless, of course, the series is about that! In that case, it should tell the story without unrelated changes.) Changes like this detract from the worldbuilding which is part of the art of fantasy and, in a separate sense, part of telling a good story. The world of the first Ranger's Apprentice book is meaningfully different from the world of the complete series.

These differences can be unnecessary obstacles to the reader. When I've introduced my friends to Lord of the Rings, I've advised them to skip The Hobbit altogether. It's a different and much lighter tone, and a much lighter plot too. Sometimes people end up liking both, but I don't want to rely on that.

And on top of that, looking back, sometimes I wish that I could have more of the stories I thought I was getting. That isn't the case in any of these examples - I thought Lord of the Rings and 1632 got better after their shifts, and Ranger's Apprentice got no worse - but there're things in other stories I regret losing.

But then, these changes help the immediate stories of the individual books. Sometimes the author isn't planning out the whole plot of the series - Eric Flint has openly acknowledged many significant ideas that showed up later in the 1632 series only came up after he published the first book. (Often, he got them from his coauthors and fans.) Or, maybe they will make plans but change them later on, like Christopher Paolini has admitted he changed major plot points of Eragon and J. K. Rowling has publicly regretted not changing the denouement of Harry Potter.

Even if authors do plan out the story and don't change it - I'm reminded of when Tolkien went back, after publishing Lord of the Rings, to try to revise The Hobbit into a suitable prequel for the trilogy. He wrote several chapters and showed them to a friend, who said it was good but not The Hobbit. I got ahold of those chapters2, and I agree. If anything, I'd go further. In an effort to prefigure the longer-range plot of Lord of the Rings, he'd removed most of the cute tone and charm of The Hobbit. Writers shouldn't forget the individual books and their immediate charm and story.

Or even, the initial books might be what's needed to bring readers into the story. The first book of Ranger's Apprentice spends a lot of time on our young protagonist's training and introduction to the world, which is probably needed to introduce him to our young readers and set up expectations in their minds for what sort of story this's going to be. At least, if they come upon him as the highly-competent quester he develops into, they might not identify so strongly with him.

I suspect early-installment weirdness was even more the case in the 1800's when novels were often serialized chapter-by-chapter. Unfortunately, I'm not familiar enough with novels from that era to say for sure. But, I also suspect it's more the case now than it used to be several decades ago when series were less common. When stories aren't being written as complete units, or when part of a story is published while the author hasn't finished revising everything yet, an author's view of the setting and story can change much more readily. So, looking back, readers see this weirdness.

(This's probably another reason TVTropes focuses so much on TV series in their article on this - TV series are often written episodically, just like novels from the 1800's.)

It's often a flaw, but it can be worked into the story. For example, Tolkien strongly implied that The Hobbit (but not Lord of the Rings) was written by Bilbo himself in-universe; fans (like myself) have frequently explained The Hobbit's distinct tone and plot style as being hallmarks of Bilbo's writing.

But even if this isn't the case, I don't greatly mind this. It's a flaw - but it's a growth mark, a sign of the story developing.

In the real world, it's a somewhat popular theory that someone aside from Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare's plays, and the Earl of Oxford has been one name proposed. However, most Shakespeare scholars reject this, and Oxford specifically died years before several of the plays were first staged.

The abortive redrafting, along with some earlier drafts, was published in The History of the Hobbit by John Rateliff. I recommend Rateliff’s book for fans of Tolkien's earlier drafts published in History of Middle-Earth, and no one else.

The first episode of Poe's serial "Narrative of A. Gordon Pym" is standard "Here's a wild story about my sea voyage", but by the end Poe had written him into a corner where he really ought to die... so Poe stopped the series at a cliffhanger!

The serial "Varney the Vampyre", anonymous and probably by multiple authors, actually changed genres (horror, detective, romance, cynical outsider, misunderstood innocent, world traveler) over its 2 years and 237 chapters. One gets the impression nobody knew what to do with the character.

The pulp series "The Shadow" had three authors under the house name Maxwell Grant over 18 years and 325 books. The Shadow was the disguise of ex-war-hero and gangland crimebuster Kent Allard, until one author decided to write The Shadow as the disguise of millionaire playboy and scientific detective Lamont Cranston (contradicting without explanation earlier novels where The Shadow and Cranston appeared together). This change of identity and genre was reversed when the first author returned to the series.

There's some clear early-installment weirdness in the Pern books. The characters and world during the first part of the first book are pretty different (a lot harsher, for one thing) than even the rest of the initial trilogy. The first book was a fixup of two novellas, and McCaffrey had no plans for a 20-odd book series (or I believe any return to most of the characters) when she was writing that first novella.