Sometimes a book leaves me wanting another book. Sometimes that other book I want is a sequel, or a what-if spinoff, but other times I wish I could read the same story told through a different lens.

For example, a few months ago, I read a book advertised as exploring why many American men don't have good friendships, and giving recommendations on how to fix that. I'd been looking forward to it both because it's an interesting sociological topic in general, and because I could use advice on how to strengthen my own friendships amid the busyness of modern life.

Unfortunately, the book - We Need To Hang Out by Billy Baker - wasn't that. Instead, I got a memoir. The author, a journalist, took the topic and focused instead on his own personal story. He interviews several sociologists and spends some time musing on their theories about friendship, but most of the book describes his own ill-fated attempts at making friends. He's a good writer, and it's a well-written story. But, I didn't come for Baker's autobiography. Even if I did come for that, he raises so many questions that I expect I'd still be wondering more about the sociological trends than about his own life. I'm left with the same questions I came in with. What is the solution to American men's loneliness? To our unprecedented lack of friends and lack of friendship? I don't know. Baker shows us the importance of these questions, but he only tosses off a few unsupported speculations toward answering them.

That book isn't the book I was hoping for; it's the story of Baker flailing around sort of trying to research for the book I was hoping for. He tried to tell the story of friendship through the lens of his own friendships, but it's a bad lens for that story.

Unfortunately, this isn't the only book I've seen which's told through such a poor framing.

Some time ago, I read Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia, by Christina Thompson. I'd subconsciously expected it to be a history of Polynesia, or an ethnographic investigation of where the Polynesians came from and how they got across all the scattered Pacific islands where they've lived since written language first encountered them. But instead, it was a meta-history: a history of the people who have explored that question, from Magellan and Captain Cook down to the present day.

Having adopted this frame, it does tell an engrossing meta-story as it dances around the central story it keeps bringing to mind - now telling of the naive Mendaña convinced he was on the outskirts of a great continent, now with Hiroa constructing an imagined prehistory from his extrapolations, now with Thor Heyerdahl drifting across the ocean on a balsa raft to prove his own prehistoric theory possible, and finally with the modern Forander and Smith throwing out contaminated carbon dating to admit the Polynesian oral epics might have some truth to them after all.

I can't fault the book. It tells well the story it tells; the only real flaw is I wish it were longer. But reading it made me want all the more that book I'd been subconsciously expecting: an ethnographic investigation synthesizing the available evidence into an anthropological tale. Once again, the book we got was the story of people trying to research or write the book I'd been hoping for.

This problem – a book that is such a poor lens for its story leaves me wanting another sort of book – is one I’ve noticed also coming up in some detective stories. For example, take Sherlock Holmes. When we first see him (in A Study in Scarlet), the story digs into Holmes' character and explores him and his detective talent in detail. We focus on Holmes because he's one of the main subjects of the book, and Watson, our narrator, is trying to understand him. But in later books and stories, as the series goes on, the audience already knows Holmes almost as well as Watson the narrator does. Holmes and Watson are no longer the interesting part of the story; they're merely there as vehicles to unravel whatever problem they're encountering. Perhaps that's one reason Doyle was getting tired of writing about Holmes and tried to kill him off. Doyle knew Holmes was no longer the right sort of character to focus stories about; he was just using him as a window into other stories.

I've seen the same thing from other writers, like Agatha Christie's Murder on the Orient Express. Her detective, Hercule Poirot, is almost a complete cypher; the interesting people are the ones he is interviewing. This static, almost impersonal, detective was actually a convention of detective fiction at the time; Dorothy Sayers was the first one to break it by making her detective a multidimensional character. But even then, in her (excellent) Nine Tailors, Lord Peter Wimsey is so much outdone by the colorful and picturesque East Anglian village in which he's investigating.

I can't fault Sayers or Doyle for writing more interesting characters than their detectives, and I can hardly fault Thompson for the interesting story of Polynesia she does tell. I want to fault Billy Baker, but that's for making the story about himself and not even realizing the superficial level of most of his friendships... and even then, I'm wondering if I'm just a different sort of person than him looking for different sorts of friends.

But I do think this's a shortcoming in how the story is told - the author is using a lens that doesn't best fit the story. If (as Baker acknowledges) he still doesn't have many good friendships and most of his attempts fizzled in ways that didn't pinpoint problems, he shouldn't tell a book about friendship using his story as a lens. If Doyle wants to write about other characters who're more colorful than Holmes, he shouldn't spend so much focus on Holmes. (He did better in Hound of the Baskervilles, where Holmes is kept offstage for most of the book.)

Sometimes a lens that's distinct from the main story it's viewing can be a good thing.

Giving readers a more relatable person as a window into events can be useful. For a fictional example, you could argue that's why Robert Lewis Stevenson's protagonist in Treasure Island is a young landlubber, Tolkien's protagonists in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings are hobbits, why Lucas's protagonist in Star Wars is a backwater farmboy, and why many other authors have made the same choice. For an example in history books, I'm remembering The Aleppo Codex, where Matti Friedman juxtaposes the history of the ancient Torah codex with his investigations into the mystery of what happened to the quarter of it that went missing sometime after it left Aleppo in 1948. He tells his own story, but he doesn't lose sight of the central mystery, and the scenes he emphasizes are those that contribute to it - such as his interview with someone who claimed to have one of the missing pages. By contrast, Baker does get distracted from theories about friendship to tell in loving detail how he tried to rekindle some of his own friendships.

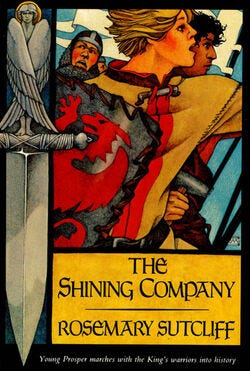

But if an author's doing that, the relatable person should himself be part of the story. Stevenson's story is about Jim Hawkins, Tolkien's stories are about the hobbits, and Lucas's story is about Luke Skywalker, at least as much as any other characters. Rosemary Sutcliff also does this well in her Shining Company. You could say that it's the story of the ancient British Battle of Catraeth, told from the point of view of a young shieldbearer - but he's the main character in every sense of the word, and the story is about him more than any of the other heroes.

Really, for all the flaws of the prolific historical fiction writer G. A. Henty, this's one thing he did well. He wrote over a hundred historical novels in the late 1800's, each focused around a resourceful boy or young man involved in a war (or, occasionally, other troubled times), whose life is intertwined with some significant historical figure. His heroes can be criticized for being too one-dimensionally heroic and lucky, and his plots can be criticized for being too formulaic - but he clearly made them the protagonists of their own stories.

If you don't want to do this, then you should try to actually make your prominent character (say, Aragorn or Obi-Wan or Squire Trelawny) a relatable protagonist, because he's going to be your protagonist. Showing him through other people's eyes can be useful in that, but if you're not going to give Jim Hawkins or Luke Skywalker or Frodo Baggins a good plot arc of their own, you can't make them your main viewpoint character.

Using the wrong lens can be a difficult problem to fix.

At one point, I tried writing a fantasy adventure novel myself. But - when the second draft was already half-written - I realized that most of my secondary characters were more interesting than my bland protagonists. I tried to fix that, but several drafts later, I was forced to acknowledge that the protagonists couldn't hold up the role I wanted them to have and wouldn't fit the story I wanted to tell, so I needed to throw out just about everything.

If you realize halfway through that you want to tell the story of Squire Trelawny instead of Jim Hawkins, or the story of the Battle of Catraeth instead of the story of a boy caught up in it, you're going to need to throw out a lot of your book. Sometimes you can save some of it, like Doyle turned Hound of the Baskervilles into a Sherlock Holmes novel halfway through writing it (thanks to popular demand for more Holmes stories). But it's going to be a lot of work.

To help avert this, authors should probe the depths their story brings up. If there're characters or questions that it raises in people's minds - consider looking into them. Beta-readers can help here; I know it did for me when I was trying to write a novel.

But in the end, in books just like in physical glasses, the same lens doesn't work for everyone. Some people (including a lot of Doyle's original audience) really liked repeated appearances of Sherlock Holmes. But other people don't, and would like a better lens on the stories than Holmes peering into them. So, this problem can't completely go away. It's just part of how people respond to stories differently.